Meeting a missionary in a Llanfairfechan cafe and mistaken for a druid on Great Orm, St Trillio’s by the sea and Conwy by night.

15 May 2013: blog | flickr | audio | map | data

miles walked: 21

miles completed: 281.3

miles to go: 779

This was an uplifting day in so many ways, especially after the previous day, which had seemed such a hard slog. My ankle continued to hurt, but did not get significantly worse despite a very long day’s walking. I walked in sandals this day whereas the previous day had been boots; maybe the sandals are easier on the flat surfaces, or maybe it was the effect of the scenery, or maybe just my spirits were high and that helps everything!

This was due to be a short day, just 12 miles from Abergele to Llandudno, as, before I set off for the day, I wanted to spend time using the WiFi at the Beach Hut café in Llanfairfechan. I wrote for a few hours before the Beach Hut opened, looking forward to my breakfast. However, when I got there, only one person was on duty and so could not do a full breakfast, just a bacon bun 🙁 Somehow, I lived through that minor disaster, sat down, munched my bacon butty, started uploading to Flickr (painful), syncing Dropbox files (joy), and writing more of the previous day’s blog.

This was due to be a short day, just 12 miles from Abergele to Llandudno, as, before I set off for the day, I wanted to spend time using the WiFi at the Beach Hut café in Llanfairfechan. I wrote for a few hours before the Beach Hut opened, looking forward to my breakfast. However, when I got there, only one person was on duty and so could not do a full breakfast, just a bacon bun 🙁 Somehow, I lived through that minor disaster, sat down, munched my bacon butty, started uploading to Flickr (painful), syncing Dropbox files (joy), and writing more of the previous day’s blog.

At the next table a group of three people were chatting and suddenly I heard them say, “the Methodist place”, and realised they were talking about one of the MHA homes where one of them was hoping a relative would be placed, quite possibly the home I would be visiting in Colwyn Bay the next week. A short while later, the group left and a couple came in, sat at the same table and pulled out a laptop. After a few minutes their computer announced loudly, "you’ve got mail!", just like in the movie.

The lady, Joy, noticed my banner and asked about the walk, and when I mentioned MHA she said in fact she was a Methodist minister. Joy spent much of her time in India working with people with leprosy and diabetes, but was currently temporarily looking after the local church as the minister had recently died. We talked about the closed chapels and the way some parts of the church were getting older and literally dying away, whereas others, like the church Esther attends in Liverpool, are growing and thriving. She also told me about a friend from theological college who was a walker and poet.

The lady, Joy, noticed my banner and asked about the walk, and when I mentioned MHA she said in fact she was a Methodist minister. Joy spent much of her time in India working with people with leprosy and diabetes, but was currently temporarily looking after the local church as the minister had recently died. We talked about the closed chapels and the way some parts of the church were getting older and literally dying away, whereas others, like the church Esther attends in Liverpool, are growing and thriving. She also told me about a friend from theological college who was a walker and poet.

As she left (my laptop still hard at work uploading files … albeit with power dropping very low) I said how good it had been to chat, and how often during the journey there had been chance yet rich meetings. "It may be happenstance, or maybe providence", I said. Joy opened her arms, "simply the Holy Spirit".

By the time I finished off, prompted by the dead laptop battery, and got the train, it was 2:30pm when I started from Abergele. The beach front cafe ‘Pantri Bach‘ was open, and with a name like that I had to stop by, albeit, sadly, skipping their sit down ‘all day breakfast’, and just grabbing a tea in a polystyrene cup and a sausage sandwich to eat on the move.

A group of young people led by a man with a clipboard stopped by an open air exercise area. I’d seen a larger one of these at an earlier resort, it almost feels like Los Angeles. I don’t know whether this was a sixth form geography lesson looking at seaside regeneration, or maybe an apprenticeship scheme for outdoor recreation, and I don’t know whether they were impressed, but certainly Abergele felt a lot more ‘open for business’ than some of the places I’d been through where everything seemed to be closed. As well as the exercise area I loved the Charlotte’s Web children’s climbing net.

It is early in the season, so not all the seaside stalls are open, but I spot a bait shop; there are many fisherman out already, and I assume even more as the season progresses. Also there is a pet-grooming stall. I can’t work out if this is just a convenient place for it, or if it is for all those pet owners who want the sand and seaweed shampooed from their pooch before letting it in the car.

At the far end of Abergele bay is an impressive castle on the hill that I have seen many times from the A55. I have assumed it is a Victorian folly constructed by a local businessman made rich on the limestone quarries rather than a Norman defence, but need to check it sometime. However, defence or conceit, it is impressive hanging on the hillside.

Further along the promenade is a large boulder, a memorial in 1995 to fifty years’ peace and dedicated to the heroism of those who died in the 1939–1945 war. While the latter is unquestionable, the idea of fifty years’ peace between 1945 and 1995 seems odd, given those who lost their lives in Korea, The Falklands and elsewhere.

The caravan parks I had passed so far had all been like municipal car parks, packed closely, I assume the legal minimum distance apart for fire prevention. In one case I saw a caravan with outward opening French windows, but so close to the fence that they would never be able to be opened. In contrast, the site at the west end of Abergele is well spaced, often just one caravan deep facing the sea, and, where two deep, staggered rather than in rows, so that the caravans behind can also see the sea. Admittedly the A55 behind may mean night-time noise, but if I was going to choose a caravan site along this part of the coast, this would get my vote.

I am trying to put my finger on the difference. This town is definitely down at heel, as virtually all seaside towns are, but still pleasant, safe, alive although quiet.

Further along the coast, the other side of LLandulas, the hillsides above the sea are cut with limestone quarries with vast conveyor belts taking the rock out along a pier to load ships. For heavy or awkward goods, whether stone or Airbus wings, there are advantages still to water transport.

An information board describes the growth of this industry going back hundreds of years, but also describes the strength of community fostered by it. What is it that makes industrialisation and its dissolution strengthen communities rather than lead to social dissolution? I don’t know whether the workers here were well treated by the quarry owners, but even if not, the South Wales valleys show that resistance against hardship can also be community strengthening. In contrast, in Flint, the chemical industry seemed to poison the hearts of generations as noxiously as it polluted the air and water.

Although there is occasional marsh land or open sands, for a lot of the day the path runs behind or on top of sea defences, sometimes rotting timber groynes, sometimes large boulders, sometimes anchor-like moulded concrete pieces, each arm the height of a man. Along this coast, railway and road often run between the villages and the sea, but the entire strip of land is narrow, constantly threatened by the waves. On a wild day like this, I wonder at the cost of maintaining the defences and whether they would be abandoned and the community sacrificed to the sea were it not for the road and railway.

[completed April 2014]

Llandulas itself is mainly visible on the coast path due to its beach caravan park and ‘Tides Café and Bistro‘; the road comes to the sea through a tunnel under the railway track and I assume the town itself behind. The road tunnel does not need to dip as the railway embankment is set high to avoid, I assume, being washed over by waves and tide, well above the roof level of the caravans that face the sea.

Although there have been many signs of man’s despoliation of the environment and the harsh elements’ destruction of the land, there are occasional signs of hope. A notice board describes the honeycomb reef worm, which has returned to these waters after 60 years, a sign of reducing pollution.

A half mile further is the main Llandulas connection to the sea, a near empty car park, public toilet and piles of those giant anchor-shaped concrete blocks, then another quarter mile behind, the vast conveyor belts that cross to the sea, some apparently disused, others still active.

A headland separated Llandulas from Colwyn Bay and on the Llandulas side of the headland is a crude squat stone and concrete hut, its walls a foot and a half thick, an abandoned explosives shed for the quarry, set as far away from quarry and human habitation as possible.

A road joins the footpath at the eastern edge of Colwyn Bay, and the waves break over the sea wall, flooding the road. The footpath and prom is above the road, so you can stand relatively dry watching the few cars that brave this stretch of road as they time themselves to drive in both directions on the coast side of the road. I can see sea-thrown pebbles on the road that would smash a windscreen.

Despite the waves, the weather starts to improve, the cloud bank of the earlier part of the day gradually clearing and blue skies and sun peeking through. The stall selling brightly coloured buckets and spades makes it really feel like the seaside. And, yes, stalls open for business, so I can get myself another polystyrene-cupped tea to nurse along the way.

There is a new steel wood and glass building being constructed on the sea front, I assume an information centre, maybe café, complete with its own small vertical axis and turbine. Further along the Victorian pier still stands, civic building of a different age albeit now derelict and home to buddleia rather than boater-hatted men in striped summer suits and wedding-cake-dress women with parasols.

The prom continues, but a sign tells you that you have now entered Rhos-on-Sea.

A tourist information board had shown various local sites including the smallest church in Wales, which was clearly on the coast road. Going round the headland at Rhos-on-Sea, the road is about ten foot higher than the prom, so I walk on the pavement rather than down on the prom to avoid missing one of the few coast-side sights. And so almost do.

I had been expecting it to be standing on the road side facing across the road, or maybe up one of the side streets running away from the sea, but instead, and I might easily have missed it, I see the roof of a tiny building down beside the footpath, the ridge of its roofline below the level of the road.

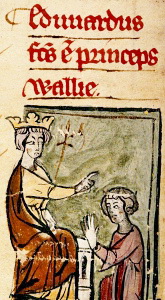

It is St Trillo’s church and one of my personal list of wonders of Wales.

It is stone walled and roofed, almost blending into the rocks behind, with a small plain cross on the peak of its low gable end. Inside, it is barely the size of a living room, with six chairs arranged either side of a small altar above a grating, the site of an old holy well.

It is plain, peaceful, a jewel and a haven.

Beyond Rhos-on-Sea I could see another seaside town ahead and a headland beyond. For a moment I thought this was Llandudno with the Great Orme beyond. However, as I drew closer I realised it was just the Little Orme I was seeing, what appears on the map as more like a wiggle in the coastline and before it Penrhyn Bay. Penrhyn is a sleepy town beside the sea, rather than a seaside town; I would guess a retirement rather than holiday destination, maybe the road sign that said, “Beach Drive (no access to beach)”, says it all.

The way to Little Orme leads through a small maze of bungalow estate, but then opens out into quarried layers with many dog walkers amongst the remains of abandoned working gear.

From the top of the Little Orme the views stretch back along the coast and over my day’s walking. Then, after a short walk through woodland and grassy scrubland, I join the road that breaches the hill and looks down upon the evening-hazed grandeur of Victorian seaside landscaping at its prime, the arch of sea leading past tall sea-front terraces and leading the eye to the Grand Pier and Great Orme itself beyond; wilderness both framed and tamed.

As I come closer I see that the hotels have grand names, the ‘Dorchester‘, the ‘Washington‘, the ‘Hydro‘; the last a reminder that the sea was at first as much a health cure as a holiday.

While there are the occasional signs of distress, on the whole Llandudno seems to have survived the 20th century and is thriving. It looks as if it never had quite the flood of amusement arcades and fun fairs of the 1950s and 1960s, and so, in its late Victorian charm, is better suited to serve a new form of seaside holiday that is less threatened by Majorca or Ibiza.

The distances are deceptive, a good mile and half along the prom. The pier is still very much alive, but I cannot see a fish and chip shop, and I was finding myself hungry again.

I had accomplished my day’s walking, and done plenty given my afternoon start, so I could walk up into the town, find the railway station, and maybe get some food while I waited for the next train. But I felt strong, my sandalled feet so much better than the previous booted day. So I kept on around the Great Orme. It looks deceptively small on the map, and indeed is just a mile across at its neck, but more like five or six miles to go round.

I would like to return, as deep in its heart is an extensive Bronze Age copper mine, only discovered in 1987. Its size, and the geographic spread of the copper mined here, speak compellingly of the complexity of trade and civilisation that was here 4000 years ago. In the Bronze Age as in the 19th century, Wales was at the heart of global industrial expansion.

It is a lovely walk, at first rising above Llandudno Pier and the Grand Hotel and looking back towards the town, then gradually climbing further past rock climbers and nesting birds. In the daytime there is a small café, but at night, once I am a short way out of the town, there are few cars and only one walker, me.

At the furthest point the views stretch along the coast both far back along the way I have come and also onwards to the west, to Anglesey and Snowdonia.

I don’t recall how we started talking, maybe she just stopped to see if I wanted a lift, but I start to chat to a lady passing in a car. When she had first seen me she had, for a moment, mistaken me for a friend of hers, a druid and a walker. I guess in long hair and sandals I only need a staff and hair shirt to complete the picture. She is fascinated by the spiritual sites of the area, both Christian and pagan.

It is often said that we are an increasingly secular nation, and indeed in many ways that is true, but also there is a great thirst for spirituality. As creatures we are made for a relationship with God, so it is no wonder that despite a culture of materialism there is that deep unfulfilled longing within. I despair sometimes that the church seems largely unable to connect to this seeking for meaning.

The Celtic church had no such problems building from the local pre-Christian understandings as well as challenging aspects of them. This was, and can be no crude 1960s syncretism, but instead both an openness to value the many true and rich things in varied beliefs, whilst holding on to a fuller truth, and a willingness to meet people where they are, whilst pointing a route onwards, a pilgrimage to follow together.

We must have talked for half an hour and the dusk was drawing in when we bade farewell and she drove on her way.

For a mile or so I trot gently back down towards the far side of Llandudno.

Llandudno spans the neck of the Great Orme, but this south-western part, overlooking the Conwy estuary, is a quieter place than the seaward facing side. There is a café, but of course closed as it is now 9pm. I had hoped maybe a fish and chip shop, but all is silent in the dimming light.

I go on along sand and sea-edge path to Deganwy where there is a halt, but sadly again no fish and chips. It is now properly dark, and as I walk the last miles along the road past Tywyn toward the Conwy Bridge, the last light fades in the west, so, as I cross the bridge, Conwy Castle is lit ahead and Llandudno shines across the water.

I knew I would be too late for the last train, it is well after 10pm, so I look for a taxi, but come to a pub first, so go in, order a half pint and ask for a taxi number, I am hungry, and tired, but have accomplished far more than I planned.

It had been a day of unexpected joy, chance yet rich meetings – happenstance, providence or simply the Holy Spirit.