in which the intrepid walker meets other intrepid walkers and cyclists, extends his vocabulary, learns mastery of cattle , and conquers weather and distance

28 May 2013: blog | flickr | audio | map | data

miles walked: 26

miles completed: 398.3

miles to go: 662

The first part of the day is a tale of two beach huts.

I get the first train to Holyhead (9:02 am, not exactly early!) and head for a café I recall visiting once some years ago, facing the docks. Although far from the promenade and beach, it is called ‘The Beach Hut‘ and has a ‘caf’-by-the-sea feel, fresh and basic, serving mainly breakfasts and lunch, but also, I discover, B&B with WiFi … if I had realised the night before …

I get the first train to Holyhead (9:02 am, not exactly early!) and head for a café I recall visiting once some years ago, facing the docks. Although far from the promenade and beach, it is called ‘The Beach Hut‘ and has a ‘caf’-by-the-sea feel, fresh and basic, serving mainly breakfasts and lunch, but also, I discover, B&B with WiFi … if I had realised the night before …

With a solid breakfast inside me I set off in stronger heart than the previous day when I think I let my food intake go down.

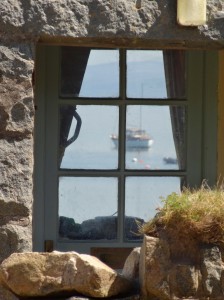

Once clear of the docks, the path leads along the promenade, past beautifully tended allotments, upright slate sculptures like the sentinel in 2001, and the Maritime Museum (with seafront café). If I’d had time I would have liked to walk the length of the Holyhead breakwater, which snakes like a sea serpent protecting her brood of docks, wharves, ferries and yachts. The latter are mostly clustered near the marina at the far end of the promenade.

Once clear of the docks, the path leads along the promenade, past beautifully tended allotments, upright slate sculptures like the sentinel in 2001, and the Maritime Museum (with seafront café). If I’d had time I would have liked to walk the length of the Holyhead breakwater, which snakes like a sea serpent protecting her brood of docks, wharves, ferries and yachts. The latter are mostly clustered near the marina at the far end of the promenade.

The foundations of the breakwater were quarried out of the hillside behind the marina, and the path leads up past this. On the way you pass two abandoned buildings. The first is solid, white, late Victorian, with four windows along its side, I’d guess at least 6 or 8 bedroomed in its prime, now fenced off with danger signs, overgrown and the word ‘technic’ spray-painted on its corner. The second is a castellated mansion, I’d guess Victorian mock-Gothic, maybe the quarry owner looking down on his creation.

While the enigmatic ‘technic’, is unofficial (read illegal) graffiti, other official wooden sculptures and mosaics line the path before it cuts up the first slopes of Holyhead Mountain.

Round the first point, a hermit’s cell or tiny chapel ahead, which on closer approach appears to be the explosive store for the quarry, far enough away not to risk sparks, but close enough to bring supplies when needed.

Further on you get to North Stack, a small rock with an old building, perhaps a coastguard station, on the cliff beside. The building is now for sale as a studio, an ideal location, but you’d need a very high-wheelbase vehicle to get to it over the near vertical ‘roadway’. An outhouse has ‘magazine’ carved above its door, so perhaps the building did duty as coastal defence. There is no lighthouse at North Stack, but a little out to sea are the skerries, with their own light.

It would be possible to do a detour over the top of Holyhead Mountain, but I decide to stick to the coastal path as it skirts the mountain towards South Stack lighthouse, and, as I drop down, I am called by name. It is the young man who served at the Llanfairfechan ‘Beach Hut’, out for a walk with his family who were visiting. If I’ve not confused people in the day, I believe the older man said he had walked from Land’s End to John O’Groats.

It would be possible to do a detour over the top of Holyhead Mountain, but I decide to stick to the coastal path as it skirts the mountain towards South Stack lighthouse, and, as I drop down, I am called by name. It is the young man who served at the Llanfairfechan ‘Beach Hut’, out for a walk with his family who were visiting. If I’ve not confused people in the day, I believe the older man said he had walked from Land’s End to John O’Groats.

Again, with more time I might have dropped down to see the lighthouse, but decided to just look from a distance. However, I do pop up to see the stone hut circles just off the path. Inside one, flowers and votive wreath have been placed, although these were never religious places, just basic homes for those scraping a life.

The coast after this becomes a succession of beautiful rocky coves and inlets, which merge into one another in my memory. A helicopter often hovered over the sea, or swung over the cliff-tops, doing exercises, I assume, out of RAF Valley. Ahead on the path I see two people wearing helmets and life-vests, I think they must be to do with the helicopter exercise, and then notice that, in the cove they are looking down into, three further helmeted and life-vested figures are making their way out of the sea.

Convinced this is a live ‘out of the sea’ life-saving exercise, I approach them. "We are coasteering," they say, "we make our way at shoreline, sometimes swimming, sometimes rock climbing, going into every inlet and sea cave." I had never heard of this before and they explain that it can take an hour to cover 100 yards. At that rate, staying in the sea all day and every day, winter and summer, it would take four and half years to get round the Wales coast. Walking, I took the easy option.

Convinced this is a live ‘out of the sea’ life-saving exercise, I approach them. "We are coasteering," they say, "we make our way at shoreline, sometimes swimming, sometimes rock climbing, going into every inlet and sea cave." I had never heard of this before and they explain that it can take an hour to cover 100 yards. At that rate, staying in the sea all day and every day, winter and summer, it would take four and half years to get round the Wales coast. Walking, I took the easy option.

Later on I spot another larger coasteering group, from their high-pitched squeals a group of schoolchildren on an activity day. It is a bit like learning the name of a plant or bird and suddenly beginning to spot it everywhere; language influences perception.

And then more rocky coves, and one small surfing beach, Porth Dafarch, which had an ice cream van in it, and a small car park and public toilets … for this area of coast development on a grand scale. On the far side of the beach as you return to the headland, a bench has a sad wreath of weathered battered plastic flowers tied to it. There is no dedication on the bench, so I assume the flowers are for someone who drowned here, one of several such memorials I’ve seen along the coast.

And then more rocky coves, and one small surfing beach, Porth Dafarch, which had an ice cream van in it, and a small car park and public toilets … for this area of coast development on a grand scale. On the far side of the beach as you return to the headland, a bench has a sad wreath of weathered battered plastic flowers tied to it. There is no dedication on the bench, so I assume the flowers are for someone who drowned here, one of several such memorials I’ve seen along the coast.

Trearddur is on the opposite side of Holy Island from Holyhead. Although we’d stayed a night at the campsite on the headland south of Trearddur, we had never visited the town itself. The scattered outskirts start around a mile before the main town, tantalising, as I intended to stop at a pub or café for a snack before continuing. I had originally thought of stopping for the night at Trearddur as it was the biggest place between Holyhead and Rhosneigr, but it was still mid-afternoon and I wanted to press on further and hoped to either find a B&B later, or go as far as Four Mile Bridge, the old crossing between Anglesey mainland and Holy Island, and either catch the train at Valley if early enough, or stop at a pub there and order a taxi back.

Trearddur is on the opposite side of Holy Island from Holyhead. Although we’d stayed a night at the campsite on the headland south of Trearddur, we had never visited the town itself. The scattered outskirts start around a mile before the main town, tantalising, as I intended to stop at a pub or café for a snack before continuing. I had originally thought of stopping for the night at Trearddur as it was the biggest place between Holyhead and Rhosneigr, but it was still mid-afternoon and I wanted to press on further and hoped to either find a B&B later, or go as far as Four Mile Bridge, the old crossing between Anglesey mainland and Holy Island, and either catch the train at Valley if early enough, or stop at a pub there and order a taxi back.

At one of these nearly there but not quite places, I see a shipping container with ‘beics-cybi-bikes‘ on the side and a couple, trying out hire bikes. I’d spotted one of these somewhere earlier on Anglesey, and realise it is a tiny ‘chain’ of cycle hire around the island, business in a box. There is a painted van also there, so maybe each one is permanently manned during busy periods, or perhaps they simply drive round the island to open up on demand.

Trearddur is ‘Tre Arddur‘, so, maybe the town of Arthur. However, unlike Bwrdd Arthur on the far north east of Anglesey, there is no sign of ancient settlements or forts that might give it its name. So, maybe ‘arddur‘ is not a name – something to look up when I have both time and internet … neither of which is in good supply at present.

While I had thought that Rhosneigr was the seaside resort of Anglesey, in fact it is Trearddur that really catches the prom atmosphere, with two ice cream vans (yes, two!), a hot dog van, and even a small cannon outside the RNLI shop. The RNLI shop proudly bears a plaque to say that Prince William and the then ‘Miss Catherine Middleton‘ carried out their very first public engagement together to name the Trearddur Bay lifeboat in 2011.

One of the vans is local Anglesey ice cream, so I have a cone of toffee fudge to enter into the full seaside experience. However, with great self-control I pass by the hot dog van as I intend to have a snack at one of the seaside cafés or village pubs. Well, that was my intention. I walk the blue-railed prom eating my ice cream, children playing on the sands, waiting for the first inviting looking premises. But there is none. Maybe I missed one that was the other side of the road, but scan as I could up and down the road I saw nothing.

One of the vans is local Anglesey ice cream, so I have a cone of toffee fudge to enter into the full seaside experience. However, with great self-control I pass by the hot dog van as I intend to have a snack at one of the seaside cafés or village pubs. Well, that was my intention. I walk the blue-railed prom eating my ice cream, children playing on the sands, waiting for the first inviting looking premises. But there is none. Maybe I missed one that was the other side of the road, but scan as I could up and down the road I saw nothing.

The only eating place is beyond the end of the prom as the road leaves the sea, and is a Crossroads Motel style building that announces it won pub of the year and has five star accommodation. Sounds a little posh for me.

I guess Trearddur grew up as a seaside town after the Holyhead railway made it easy to get here from Liverpool and even London and the Midlands. Looking at the map there is a substantial built-up area about half a mile behind the prom front, which is probably the original village and perhaps where you’d find a pub or village shop. The prom is just that, a prom, with seaside properties behind.

I guess Trearddur grew up as a seaside town after the Holyhead railway made it easy to get here from Liverpool and even London and the Midlands. Looking at the map there is a substantial built-up area about half a mile behind the prom front, which is probably the original village and perhaps where you’d find a pub or village shop. The prom is just that, a prom, with seaside properties behind.

The road cuts off a tiny headland and then meets the sea again at a small beach before leaving the last of the houses, one of which, a part-yellow painted bungalow, has the most lovely rainbow-coloured mosaic cross hanging in its gable. Then through a caravan site you come again to the clifftops, which continue on to Rhoscolyn, the next little port three miles or so further on.

The coast here is less spectacular than near South Stack, and the cliffs very much lower, but has several natural arches. However, the high spot is near the end.

At one point, where the path crosses a tiny stream along a causeway, there is a side stream coming straight from a spring in the hillside, the water head enclosed in a small dolmen-style stone enclosure, less than a yard across, so that the waters come bubbling fresh from a dark manmade cave. I wonder if it is a holy well of some sort, but there is nothing marked on the map.

At one point, where the path crosses a tiny stream along a causeway, there is a side stream coming straight from a spring in the hillside, the water head enclosed in a small dolmen-style stone enclosure, less than a yard across, so that the waters come bubbling fresh from a dark manmade cave. I wonder if it is a holy well of some sort, but there is nothing marked on the map.

Eventually, a coastguard station appears on the high spot of the cliffs ahead, but crossing the last stream before it there is another, semi-sunken, stone structure, this time the size of a garden shed. There are two parts, one like a small open-topped room, perhaps six foot square; steps lead down into it with a whatnot-style triangular stone across each corner to form rough seating for four. The base is filled with water; not the clear water of the previous well, but rich red-orange, like stagnant water in an old rusting oil barrel. It did not look inviting, but I guess is good for joints, or, as was suggested to me later, for pregnant women needing iron. On the downstream side steps lead to a smaller area with two small benches facing one another over the water.

At first, from the state of repair, I assumed it was a few hundred years old, but then noticed, up the hill, what looked like a small but ancient-looking church or hermit cell. On the map I later realise the well is marked as St Gwenfaen’s Well, but not the church on the hill. ‘Well Hopper‘ gives a detailed description of the well, and also of St Gwenfaen‘s life. The website for the church of St Gwenfaen at Rhoscolyn also has information and evidently Rhoscolyn used to be called Llanwenfaen. A description in Sacred Springs says:

‘… Ffynnon Wenfaen was particularly renowned for curing depression and mental illness. Two white quartz pebbles used to be thrown in as an offering after drinking the water, a custom surely derived from the saint’s name – wen fain = white stone.’

So, not joints or rheumatism, but drinking the water – yuck!

The coastguard station on the cliff top is no longer in regular use; I guess mobile phones have reduced the need for human lookouts, although not entirely, given (i) the level of phone signal available and (ii) your ability to phone when your boat has just capsized. I read on the side of the building that there are plans to reopen it with volunteer staffing – David Cameron, here is Big Society for you.

A couple with their children are also looking and have come from the campsite at Rhoscolyn where they have a caravan. Unlike some of the semi-retired people who spend large proportions of their time, they can only spend the odd weekend, and are finding the combination of rising site fees and also fuel costs a problem. When you can come for weeks at a time, both seem reasonable, but with the trip from Liverpool costing them £50 in petrol, they are wondering how long they can afford to keep the caravan going.

A week or so later I hear a similar story from Caroline, the landlady at The Lion in Tudweiliog. The caravan sites nearby are a major source of custom, but due to fuel costs people are coming less often, and when they do come, as at the club house in Monmouth, they eat out less. "Some families have come for years and used to have three or more meals here in a week, but now maybe once, if that", she tells me.

The path leads onto the beach at Rhoscolyn, and at the far side should end up back on the cliff, but there are lots of notices below houses on the cliff tops saying ‘Private’. Now it seems so obvious that if the path leads onto a beach you need especially bold notices to say how to get off, as there is no beaten path across the sands taking you unerringly to the next waypoint.

The path leads onto the beach at Rhoscolyn, and at the far side should end up back on the cliff, but there are lots of notices below houses on the cliff tops saying ‘Private’. Now it seems so obvious that if the path leads onto a beach you need especially bold notices to say how to get off, as there is no beaten path across the sands taking you unerringly to the next waypoint.

Happily, a family, grandfather, daughter and grandchildren, are making a spectacular dam on the beach, and point me to where the Coast Path sign is. It turns out that the man has cycled John O’Groats to Land’s End with his other daughter in his 60s and would love to do the return trip in his 70s. Earlier that day I’d met another man who had walked it some years earlier.

I find the sign, but it is very confusing. One Coast Path arrow points along the road behind the beach. That is reasonable: the map shows this as an alternative route if the tide is high. Another arrow points back to the beach from where I have come. A third finger has a footpath symbol, but no Coast Path roundel, and points along a path through a small painted gate. So, I took the fourth way, the one with no arrow at all.

Now, I know it sounds foolish, but along the way it is not unusual to find the coastal path signs only pointing in a single direction around the coast, sometimes a single arrow post, usually pointing the way I have come as the clockwise signposting seems slightly better than the anti-clockwise. In some cases, if you scan you can see a matching sign for the other direction, perhaps a little along a road; in some cases they expect the other way to be obvious, and in some cases it’s plain oversight. In the latter two cases, you can sometimes work out the right way to go by assuming the sign is designed for the people coming the other way, and guessing where they are expected to come from.

I still do not know which of these was the case, whether they were in fact directing you onto the beach and there was another way off beyond the private notices (although at high tide I can’t work out how), or whether you were supposed to follow the footpath that didn’t have the Coast Path roundel. But anyway the choice I made was, it turns out, wrong. I’d hoped that very soon there would have been a side path, taking you behind the private properties and back onto the cliff path, but it became evident that this was not going to happen, so I simply looked out for the first roads to the right and took them.

I ended up in a road leading only into the Silver Bay Caravan Site, but, rightly, assumed there would be beach access and was helpfully guided in the right direction by one of the residents, and so ended up on Silver Bay. It is now cloudy and has been spotting rain since I met the family on the sands. I can see from the map that the path leaves the beach partway along as there is no route round the final headland of Holy Island, and the path cuts across the tip, but can I see a clear bold sign? … of course not. However, in this case it is not simply subtle, or hidden, but absent. I notice a set of steps climbing the dunes to the left, and go to explore, but there are no Coast Path arrows, so I turn to go on, the correct way must be further. However, looking at the map again, and the position of the woodland that partially edges the bay, in fact these steps are precisely the way.

I ended up in a road leading only into the Silver Bay Caravan Site, but, rightly, assumed there would be beach access and was helpfully guided in the right direction by one of the residents, and so ended up on Silver Bay. It is now cloudy and has been spotting rain since I met the family on the sands. I can see from the map that the path leaves the beach partway along as there is no route round the final headland of Holy Island, and the path cuts across the tip, but can I see a clear bold sign? … of course not. However, in this case it is not simply subtle, or hidden, but absent. I notice a set of steps climbing the dunes to the left, and go to explore, but there are no Coast Path arrows, so I turn to go on, the correct way must be further. However, looking at the map again, and the position of the woodland that partially edges the bay, in fact these steps are precisely the way.

The rain has started properly now, so I am glad of the tree shelter and glad also that the path is fenced on both sides, so no decisions to be made and no chance of going wrong!

The woodland gives way to farm track and then that to a small lane, which would have been pleasant if not for the rain. I’d not brought my waterproof overtrousers, so soon my trousers were soaked through, but my top half was dry. After a while, a sign points to the right, where a sign says it is a permissive path not open in the winter, but there is still a heavy chain across the kissing gate. I almost continue along the road way, but then look harder and realise the chain with padlock is simply looped over a post, as bailer twine is sometimes, to stop the gate swinging open … so if you are ever walking this way and see a chain, do not give up!

The woodland gives way to farm track and then that to a small lane, which would have been pleasant if not for the rain. I’d not brought my waterproof overtrousers, so soon my trousers were soaked through, but my top half was dry. After a while, a sign points to the right, where a sign says it is a permissive path not open in the winter, but there is still a heavy chain across the kissing gate. I almost continue along the road way, but then look harder and realise the chain with padlock is simply looped over a post, as bailer twine is sometimes, to stop the gate swinging open … so if you are ever walking this way and see a chain, do not give up!

And I was glad I had persisted, as it leads through an idyllic area of scrub woodland and wetland (the latter pretty well boarded in the muddiest areas), I assume some sort of nature reserve. At the far end the gate has no chain (!) and you are back on the road for a short while, before turning off down a farm track round the back of a farmhouse, across a farmyard through a narrow gap between buildings (breath in), along a field, where I almost miss the path arrow half lost amongst the hedgerow, and finally onto the (soggy) edge of the estuary/strait between Holy Island and Anglesey mainland.

As the Telford causeway and newer dual carriageway largely block the flow of water through the strait it is very estuary-like in terms of the salt marsh and mud, but given how narrow the strait is at Four Mile Bridge, perhaps this would have always been so. And, although I had a few miles of wet walking to go, I was on the home stretch to Four Mile Bridge where I would go into the warm, hopefully not soak the place too much in the process, and sup a half pint while waiting for a taxi.

Well, that was the plan …

As I draw near to Four Mile Bridge, there are a number of boats on the banks, but no obvious sign of a pub. I was sure I had driven across this once and seen a pub, but it must be a different bridge elsewhere. My waterproof jacket was keeping my top half dry, but below the waist my trousers were soaked and dribbles had run off into my boots, so that each step squelched. I really wanted to just get back.

It looked like the main body of the village was on the Holy Island side of the bridge, so I walked a hundred yards or so in that direction until I came to a triangular village green. Surely this is where the pub would be. There is a hairdresser and a sign for another shop, but no sign of a pub. If there is no pub here, then there must surely be no pub at all.

Walking back to the bridge I look up the road in the other direction, and it is clearly just scattered housing. A mile or so on is Valley, but I have no idea what I will find there; I have driven through it and seen restaurants and shops, but have no idea if there is anything that would be open now. Certainly I would be too late for the last train.

The idea of waiting somewhere, whether here or Valley, maybe half an hour or more, in the rain for a taxi was not inviting.

The alternative is to continue to walk the six or so miles to Rhosneigr. It is after seven, but I will not be taking photographs in the rain and there is a substantial amount of beach walking that will be quick.

I get what shelter I can under the wall of the bridge, put the camera in the waterproof bag inside the rucksack, swap maps over inside their plastic case, with only the odd soggy corner and rain drop smudge as I try to protect them with my body from the persistent rain, and set off.

Later during the walk I discover that if I had walked a couple of hundred yards or so beyond the green in Four Mile End, I would have come to the Anchorage Hotel, situated towards the western edge of the village. As I have found elsewhere in the walk it is so hard to know what lies within walking distance of the path.

Although I’d peeked at the map, it was hard to read under the rain-dark sky and my mental model was a short walk along the riverside and then a long beach walk past Valley airfield to Rhosneigr. I think the fact that the Coast Path cuts off the south-west corner of Holy Island had shrunk the distance along the water’s edge. In fact the largest part of the journey is the riverside part, with just the last two miles on sand.

I am writing the last part of this day some time later, and have no photographs to remind me, so am struggling to recover the details from a morass of grey-skied, rain-soaked memories. Happily it is one of the better signed parts of the Anglesey coast path, as reading the map in the rain was not easy.

From the bridge you walk a short distance up the road on the mainland (as in mainland Anglesey) side of the bridge, then turn right, I can’t recall if it is initially a lane or instantly a farm track, but certainly quite soon you go through a gate into cattle fields, where the cattle are not visible in the fields, but their traces are very obvious underfoot.

After a while I came to a field where the path is signed towards a more bushy corner where bushes and fence converge into a short, three-foot wide, maybe six-foot long pathway ending in a stile. Except that wedged into the pathway were two cows. One backed out as I approached, but the other had its head by the stile and its whole body on the pathway, and could only get out by careful reversing, which it was either unwilling or maybe unable to do. Furthermore I was at the end I wanted it to move in, so it was hard to encourage it to move.

I pondered the situation for a while. Serious, including fatal, injuries, are more common from cows, but these are usually farmers suffering crush injuries. In general it is not a good idea to be between a cow and anything solid. I could see no other way round, so sized up the options and decided that the thick bushes looked a safer option than the barbed wire fence (images of cheese-wire-chopped Alan in the next field), and started to see if I could squeeze past. However, as soon as I started, although before I was fully in the gap, the cow moved backward a half pace. I backed off and waited, hoping she would continue to move backwards, but no, she stopped as soon as I backed off.

In the most gentle yet commanding voice I could muster I gave her a slap on her side and said, "come along now" …

… and she did.

I was Alan, braver of rain, master of cows, invincible.

But still wet.

For a while the memories are simply rain-soaked fields, and then the path came out into a ford over a small river. I can’t recall if there were stepping stones for pedestrians, or simply a damp paddling crossing; my feet were so wet I would not be able to tell.

Opposite the ford I continued through the open gate, along a track, and eventually passed a house that was in the process of renovation, into another field, and the path ran out. After scouting about I started to backtrack, looking for signs along the way, until I got to the riverside, and saw that indeed there was an arrow telling you to turn right along the water’s edge, which I had missed in the combination of half-light and the clarity of the open gate ahead.

Walking sometimes nearer, sometimes further, from the water, it was unclear whether I was seeing across the water, Holy Island, or twists of my own bank; certainly it seemed to go on for ever. In fact this part, moving mainly cross-country following the side of the estuary/river, was about four miles (without the wrong turning, which probably added a half-mile or so). However, these were not the fast beach miles in my mind as I’d set off. So the hours passed and the sky was getting darker with sinking sun as well as grey clouds.

Eventually, with a feeling of relief I came to the edge of Valley airfield, from which Prince William flies.

There was no sign of the Prince, nor indeed any plane or person foolish enough to be out in this weather. Along the perimeter fence signs warning you not to loiter, as if I was likely to spend time contemplating the view, with rain soaking my underpants.

After maybe a mile, or maybe a little less, of blissfully fast and easy walking along concrete and gravel, it was with joy that the path came out onto sand and I saw the sea.

It would be a lovely walk in the sun, but in the falling dark, I trudged it as fast as I could, knowing that at the other end I had to negotiate the meandering marshy estuary to cross to Rhosneigr. I had seen a bridge, somewhat inland, but how you got from beach to there was uncertain.

So, with the rain still falling, I came to the end of the beach, with Rhosneigr literally a few hundred yards away, but with the river between. According to the map, the path should cut across the last spit of sand, but in the dim light I had seen no sign, so I ended up making my way round the steep sandy banks of the river until eventually the small meandering estuary narrowed and I spotted the path. Then blissfully it was an easy walk to the footbridge, which comes out just below the campsite.

At twenty to ten, I opened the campervan doors, reached in to the shower area, and one by one stripped off layers while still standing at the doorway, depositing the dripping boots, trousers and waterproof anorak into the wet room (I should note that I closed the caravan doors before depositing the dripping underpants).

Under my (also waterproof) under coat, I was amazingly dry, with just the odd damp ingress around neck and wrist.

I was soaked, I was exhausted, my feet hurt, it had been the longest day I had walked so far, and indeed would walk on the journey, twenty-nine miles, and probably the wettest, but I was not down. I was elated; I had challenged distance, I had challenged rain, I had even challenged a recalcitrant cow, and I had won.

In some ways the Angorfa system is a little impersonal, but knowing that I have a keycode, rather than disturb the landlady, was welcome the night before when it was nearly 9pm when I arrived in Abersoch. In many ways like the MorphPOD experience. I have been staying in a lot of B&Bs and for the purposes of the walk, I often learn a lot from chatting to the owners. However, if travelling with Fiona for pleasure, we usually prefer a Travelodge, Days Inn, or other roadside motel, for the ease of late night check-in and, to be honest, the less personal, but slightly more private feel.

In some ways the Angorfa system is a little impersonal, but knowing that I have a keycode, rather than disturb the landlady, was welcome the night before when it was nearly 9pm when I arrived in Abersoch. In many ways like the MorphPOD experience. I have been staying in a lot of B&Bs and for the purposes of the walk, I often learn a lot from chatting to the owners. However, if travelling with Fiona for pleasure, we usually prefer a Travelodge, Days Inn, or other roadside motel, for the ease of late night check-in and, to be honest, the less personal, but slightly more private feel.

At one point, where the path crosses a tiny stream along a causeway, there is a side stream coming straight from a spring in the hillside, the water head enclosed in a small dolmen-style stone enclosure, less than a yard across, so that the waters come bubbling fresh from a dark manmade cave. I wonder if it is a holy well of some sort, but there is nothing marked on the map.

At one point, where the path crosses a tiny stream along a causeway, there is a side stream coming straight from a spring in the hillside, the water head enclosed in a small dolmen-style stone enclosure, less than a yard across, so that the waters come bubbling fresh from a dark manmade cave. I wonder if it is a holy well of some sort, but there is nothing marked on the map.