a day on the coast path with no sea, oak wood and hydroelectric, exhausting, depressing, and encouraging at the end

10th June 2013

Penrhyndeudraeth is where the toll bridge crosses the Afon Dwyryd, which runs down the Vale of Ffestiniog. The official Coast Path for some reason does not cross the toll bridge. I had assumed this was because it does not carry pedestrians, but in the Lion in Harlech I was told there was a pedestrian toll (I think about 6p), so maybe it was deemed too dangerous to funnel walkers onto? However, as it is closed for works, it is a moot point. I just hope the works will include a pedestrian walkway, as this would save the ten-mile diversion up the vale that takes up the majority of this day.

Penrhyndeudraeth is where the toll bridge crosses the Afon Dwyryd, which runs down the Vale of Ffestiniog. The official Coast Path for some reason does not cross the toll bridge. I had assumed this was because it does not carry pedestrians, but in the Lion in Harlech I was told there was a pedestrian toll (I think about 6p), so maybe it was deemed too dangerous to funnel walkers onto? However, as it is closed for works, it is a moot point. I just hope the works will include a pedestrian walkway, as this would save the ten-mile diversion up the vale that takes up the majority of this day.

Out of Penrhyndeudraeth, the path quite quickly enters woodland, which is sometimes pine forest, but sometimes oak plantation perhaps 50 to 100 years old. At one point I spot a broken tree trunk, I guess snapped in a gale, with a silver birch sapling growing from its broken top.

The path runs roughly parallel to the Ffestiniog Railway, sometimes only yards away, sometimes only discernible by the occasional train whistle. At one point, when the track is visible through the trees, there is a rusting water butt beside the track, like a giant bathtub, and echoing that thought, on the surface of the water float two yellow plastic ducks.

In the woods the path is well signposted at each junction, but along some of the small paths, someone has placed red tipped bamboo canes and the occasional dab of red paint on a stump or tree trunk. Although strictly unnecessary in some places where there is only one clear path through the trees, on the bendy sections, where the path switches back on itself, or takes unexpected turns, the red markers are welcome reassurance.

Although the path is well signposted, you do have to keep your eyes open, and there is one significant exception. At a large Y-junction in the woods there is no signposting. It may be that the signposting was there once, but has been broken down and crushed by passing forestry machinery. One path heads off to the right, but seems to grow gradually less as I scout down it, so I return to the larger path, a small forest roadway, which runs above the railway. At some point I need to cross the railway, but looking down the smaller path it appears more to double back, so I decide to take the larger one. This turned out to be the wrong decision, but by the time I realised, I had gone so far I continued on until it hit the minor road that runs back down and eventually meets the correct path.

This diversion added a mile or so to the day, and meant I spent longer road walking later, but did mean I got to see the small upper lake up in the hillside as well as the slightly larger Llyn Mair.

The signpost for the Coed Llyn Mair nature reserve describes the woodland around the lake as one of Wales‘ ‘rainforests’; the moist atmosphere under the thick oak cover encourages all sorts of mosses and lichens. Rosie, who had walked in the opposite direction a few days previously, described the woods here as magical, making her feel Druid-like. Sadly the wrong path meant I missed some of this, including the reclusive hermit and his bivouac that she spotted.

By the time the road met the footpath at Tan y Bwlch, the Oakeley Arms was a welcome sight.

With a meal inside me, a sort of late breakfast/early lunch, I set off again. The main A496 runs alongside the river and would have been the fastest way down the valley, maybe an hour and half at most to get to the far side of the toll bridge, rather than the four and half hours it actually took.

However, the A496 is busy normally, and even busier given the closed toll bridge. With no footway at all and heavy trucks and fast cars, even the couple of times when the path touches it for 50 yards at most, it feels dangerous and I find myself pressed flat against the wall. The coastal cycleway, which would normally cross the toll bridge, also avoids the A496. As well as being dangerous for the cyclists themselves, the bendy road means that cars are forced to either slow down to the pace of the cyclist or overtake dangerously.

Here as in other places, I realise just how terrible it is, in an age of global warming and growing obesity, that the inclusion of a cycleway and footpath is not a standard feature of any road.

Happily the short stretch of road between Tan y Bwlch over the river bridge to Maentwrog does have a footpath.

In Maentwrog, the church of St Twrog declares it is an ‘Eglwys Masnach Deg‘, a ‘Fairtrade Church‘, and has a prayer posted on the notice board labelled ‘Croeso’ (welcome), starting:

O Dduw, gwna borth yr eglwys hon yn

ddigon llydan i dderbyn pob un sydd angen

cariad dynol a chyfeillgarwich

And an English translation, headed "Welcome, Benvenuto, Welkom, Shalom, …"

O God make the doorway of this church

wide enough to receive all who

need human love and fellowship

Thereafter, the Coast Path is signposted up a small lane. About a half mile up the lane the footpath is signposted off to the right. It will rejoin the same lane after a mile or so, cutting off a small amount of distance, but taking the path entirely off-road.

I must admit my heart does drop now when I encounter these off-road inland sections of the path, but I pressed on. On the map I could see that the footpath immediately diverged from another path, and this was exactly the case, so I took the leftmost, and larger, path, and continued up the hill. The views are spectacular (even if you are tired!), although you need to remember to look back sometimes.

After a while a sign announces it is ‘Coed Camlyn‘, and I think of the ‘Battle of Camlann‘ reported in one of the early documents about Arthur. Sure enough, around the turn of the path is a small castellated tower, only made of concrete not stone, so probably not Arthurian in origin.

A sign on the tower says it is for pressure relief. I know that down below there is a hydro-electric station driven from Trawsfynydd Lake; I assume that this tower is connected to the underground pipes so that, if for some reason the turbines seize up, there is somewhere for the water to go, like a giant toilet overflow. Only this overflow is perhaps 15 feet in diameter: if thousands of gallons of water were to suddenly spurt out of this then where I am standing would be very wet indeed.

The path then heads down the hill and comes to where the twin water pipes, each around five or six feet in diameter, emerge from the ground and head down the hillside on their final approach to the turbine hall below. I can only imagine the power of the water flowing down these pipes rushing from the mountain above. A small building where they emerge says it houses high-pressure valves; high-pressure valves indeed, each one will be holding back several thousand tons of water.

After breaking my reverie, I return to the pathway, only to find a turning circle, the end of the line; it is a path to service the valve house. There is a small stile, but no onward path as the slope below is steep and thickly covered in bracken and brambles. I may have only been a few hundred yards from the power station, but I had to turn back. Looking again at the map I realised that the Camlyn tower was at the top of the hill I should have skirted to the south of; although I’d taken the leftmost branch at the beginning there must have been another path branching left further on.

Despite looking carefully all the way back to the road, and then scouting back once more on my tracks for a few hundred yards, I never found the missing sign. So I took the road instead, my initial misgivings, sadly, justified. Later I found the other end of the path, well signposted.

On the road back down the hills towards the power station, there is a picture postcard cottage beside the road. Only as you draw closer you see just behind the cottage, running beside its cottage garden, is an enormous water pipe, far larger than those I’d seen earlier, maybe 8 foot diameter. I wonder if the dull rumble of water rushing through it keeps the cottage dwellers awake at night, or maybe scares away moles from their grass.

Down at the power station, Maentwrog, I chat to an engineer taking a fag break by the gateway. He talks about the twin turbines driven by the two pipes, but has no idea what the single large pipe is for; it heads far away across the landscape, maybe to supply a new power station.

This plant is owned by Magnox, which is also responsible for running and decommissioning Britain‘s end-life nuclear power stations including those at Wylfa and Trawsfynydd. I have a feeling this was a semi-random decision at the time the power industry was privatised. The old Magnox stations were a poisoned chalice that could not be sold off, just as the new planned nuclear stations can only be built if the government underwrites decommissioning. So they were retained in a government-controlled company – Magnox. The Scottish hydro stations went into their own company, but the few non-Scottish hydro stations didn’t fit anywhere, so were tossed into Magnox as well.

The Coast Path leads up to the final steep climb of the day. Partway up there is a red sign on a track branching to the right, ‘Path in dangerous condition’, but then a few yards later the Coast Path arrow indicates joining the very same track. I think, having walked the track, the danger sign is for something now past … but it did not inspire confidence.

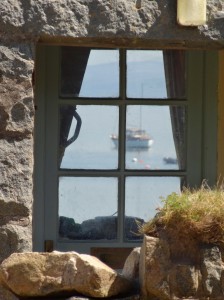

The track (safely) leads past a small mountain lake, either artificially made or at least height managed by two small dams, and then back down the hillside, and, eventually, at 5pm, for the first time this day, on the Wales *Coast* Path I see the sea. Then, a short time later, I am at the road leading to the southern end of the closed toll bridge, less than a mile away from where I started the day, seven hours previously.

Thereafter the path is on the flat. The expanse of Morfa Harlech stretches out towards the sea, but it is a nature reserve, so the Coast Path skirts its inland edge along the side of a dyke, not daring even to take the well-made track following along the seaward, and nature reserve, side.

Eventually you reach a small industrial unit and the Coast Path is signposted onto a straight and apparently endless concrete road, which is crossed periodically by other concrete roads. It feels as if it is the site of an demolished industrial plant, with concrete roads between the now-gone buildings. But then I notice that the raised grass between the banks is pockmarked with breather tubes, as if something is decaying below. I imagine anything from noxious chemicals forever poisoning the land, to abandoned war-time nerve agents.

Later, at the Lion in Harlech, I learn that this was a war-time site, but is now the county recycling centre. The vented area is collecting methane. I had noticed a slight smell at one end of the concrete path, which was presumably near where new material was being buried, but nothing in the grassed vented areas, so it is clearly being well managed. They also produce compost, which is then available free to gardeners, although it evidently took them a while to sort this out as the early batches had too much salmonella and so could not be used.

Coming into Harlech, the castle dominates everything, the railway station huddled apologetically below its grandeur. The castle is now about three quarters of a mile inland, standing high on a precipitous rock above a flat plain where the station and modern estates gather, rather like in Edinburgh, always looking upwards to the castle. But it was not like this 800 years ago when the castle was first built. At that point it was on the coast, the precipitous rock face cliffs falling directly into the sea.

Of course further back again, the whole of Tremadoc Bay, indeed large chunks of the entire Cardigan Bay that stretches across the whole west of Wales, would have been dry land, drowned as the southern part of the {UK gradually sinks, seesaw-like as Scotland rises with post-ice-age rebound.

For Wales and even more so Cornwall with its huge drowned river valleys, it is like being the small child suspended in the air on one end of the seesaw, while your elder sibling sits on the far end: eventually the glaciers left Scotland, and as when the older child gets bored and jumps off the seesaw, the smaller child comes thumping down.

However, that is the overall state, and even in areas where the land is still sinking (a few centimetres a year), sand deposition can be far faster. Much of south eastern Snowdonia drains into Tremadoc Bay, down Glaslyn, tamed by the Ffestiniog Railway causeway, and down the Vale of Ffestiniog itself. The rush of water after winter thaw, the lashing winter rain or sporadic summer downpour turns each mountain stream into foam-filled fountains, rushing down, rolling stone upon stone, ice-sharded fragments tumbled into dust, moraine soil, dumped by the receding glaciers scored from stream sides, washed down together into larger waterfalls and rushing rivers that gradually spread and slow until, youthful force spent, their last ageing strength is broken against the power of sea and tide. Like an old man putting down his burden, or maybe a walker taking off his rucksack at the end of the day, the assorted grits and silts, soil and stones are dumped, tide sorted, wave washed, wind scattered, grass gowned, thrown into unlikely dune ranges, or spread thin in salt marsh.

Thus is the land we stand on. Built hard by toil and tumult, but, as easily, washed away by the next spring tide.

The main town of Harlech is up on the hillside, behind the castle. There are slow roads that cut up diagonally across the hillside, but when you are at the station, directly below the castle, there are two roads up, the more obvious, and easier, one is a 25% slope, or 1 in 4 in old terms, and that is the gentle slope. There are some steps in parts for the walker, but if you drive up you need to believe in your low-gear torque.

It was after seven when I arrived, and most of the shops and cafés long closed.

At the beginning of the day I had wondered if I’d be able to make it all the way to the campervan at Tal-y-Bont, so it wouldn’t matter how late I was. However, this was still twelve miles away, so I would be trying to navigate the final parts in the dark. I was also so exhausted by this point, that I had decided simply to find somewhere to stay in Harlech, and set off first thing to continue south.

So, amongst the closed shops, I was scanning for a small hotel or B&B. It seemed a nice place to stay here, high overlooking the sea that had eluded me the whole day, with the mountains as backdrop, and castle in near focus.

A couple of restaurants were also closed, I guess still not high season, but at a crossroads a chalkboard advertises the Lion Hotel, which oddly has no name sign on the actual building, just a sign saying ‘Bass in Bottle’, a menu board and an Irish Tricolour. There is scaffolding up, so maybe the pub sign is just temporarily taken down, and I forgot to ask why.

Ah yes, the other signage, a small hanging sign in the window, ‘No Vacancies’, but I went in anyway to ask if they knew anywhere else I could ask.

It had been a depressing day, hard work, wrong paths, aching feet and legs, and no sea. Not a day where I felt I’d learnt anything of any significance, merely covering some miles that were on the official path, but would probably disappear from it once the toll bridge reopens.

But small kindnesses can change everything.

Although they had no rooms themselves, the lady behind the bar and a young man who was obviously connected with the pub started to discuss options, rang one place and, when another lady came in, she started to look up the phone number of another option on the internet … a laptop on top of the (not alight!) woodstove under the chimney breast.

Then they noticed the banner on my rucksack, and remembered when Christian Nook had come by as part of his all-Britain walk last year. He had refused a bed for the night as he is rough sleeping to highlight ex-Forces homelessness, but they had given him use of a shower and a man from the village had taken him home for a meal, before he eventually slept in the covered alley that leads to the beer garden. Since then they have been keeping watch on his website and knew his progress.

They asked about my walk, gave me a drink and food, and the lady behind the bar gave me her night’s tips to go towards the charities. When accommodation was proving hard and I considered a taxi to Tal-y-Bont, they reminded me that the last train had not yet left.

While waiting, the young man talks a little of a trek he took across one of the pilgrim routes in southern France. He’d like to do the Spanish Camino some day too. He belittled the tiny path signs in Britain compared to France where large markers were painted on roadsides and arrows painted on the track, none of our British pretty-prettiness.

Eventually I took the other road down the hill to the station, round the north side of the castle, at 40% not a slope I’d like to drive up, and walking down definitely better than walking up.

Eventually I took the other road down the hill to the station, round the north side of the castle, at 40% not a slope I’d like to drive up, and walking down definitely better than walking up.

My feet still hurt, my muscles were still in knots, I was still tired all over, but my spirits, which had been depressed all day, were lifted by the kindness, interest and encouragement of The Lion.