I had ‘wild camped’ in Aberystwyth to get an early start. By ‘wild camped’, I mean there is a stretch of the seafront where campervans are tolerated to stay overnight, indeed some have levelling chocks under their wheels. Sitting under the castle, the wild camp is actually on the Coast Path.

I had ‘wild camped’ in Aberystwyth to get an early start. By ‘wild camped’, I mean there is a stretch of the seafront where campervans are tolerated to stay overnight, indeed some have levelling chocks under their wheels. Sitting under the castle, the wild camp is actually on the Coast Path.

The Coast Path leads past the quayside, and up a narrow alley and steps behind the ‘Rumours’ bar. Beware, these are slippery when wet; I slid down on my way to collect the van at the end of the day, painful enough, but probably would have been worse without the rucksack to break my fall.

The path then leads to the bridge over Afon Rheidol, and partway across is a plaque commemorating one of the early events of the Welsh language movement:

On this Bridge Cymdeith Yr Iaith Gymraig

held its first non violent protest for equality

for the Welsh language,

Saturday 2nd February 1963.

I had driven this way many times before, but never seen the plaque until now, walking across. However, walking the Coast Path I will miss the more famous sign of Welsh nationalism. Driving out of Aberystwyth, a few miles along the road towards Llanrhystud, there is a red painted rock bearing the words:

Cofiwch Dryweryn

I had seen this many times, but only realised a few years ago that this was a memorial to the drowning of the village of Capel Celyn and then Trweryn Valley to provide water for Liverpool‘s growing 1960s industry. The words on the rock translate, ‘Remember Trweryn‘. Reading Roy Clews‘ ‘To Dream of Freedom, I’m learning a little more of the events of the time, some sad, some amusing. There were major protests at the official opening ceremony of the Trweryn Dam in 1965, but one group of hardcore nationalists did not take part, not for ideological reasons, nor because they were intercepted by Special Branch, but because they missed the bus.

I had seen this many times, but only realised a few years ago that this was a memorial to the drowning of the village of Capel Celyn and then Trweryn Valley to provide water for Liverpool‘s growing 1960s industry. The words on the rock translate, ‘Remember Trweryn‘. Reading Roy Clews‘ ‘To Dream of Freedom, I’m learning a little more of the events of the time, some sad, some amusing. There were major protests at the official opening ceremony of the Trweryn Dam in 1965, but one group of hardcore nationalists did not take part, not for ideological reasons, nor because they were intercepted by Special Branch, but because they missed the bus.

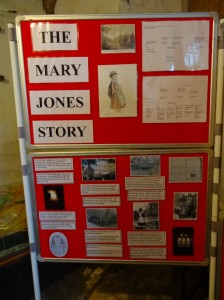

Back to the bridge and the Welsh language movement. Nowadays every road sign in Wales is bilingual, but it was not always that way. As a child in the 1960s everything official was in English only, despite the fact that Welsh was the majority language in many counties of Wales. Indeed, from Llŷn down the Gwynedd coast, in every pub, café or shop, if you listen to the locals speaking it is nearly always in Welsh.

There were already some changes, even by that point, and in school I had token Welsh lessons, but if I had been in many schools 50 years earlier, I would have been punished for speaking Welsh at all.

However, it was the non-violent protests of the Welsh language movement, given extra impetus by the common anger at Treweryn, that changed the typographic landscape of Wales as dramatically as the dam changed the topographic landscape of Treweryn.

However, it was the non-violent protests of the Welsh language movement, given extra impetus by the common anger at Treweryn, that changed the typographic landscape of Wales as dramatically as the dam changed the topographic landscape of Treweryn.

Back to the sea, Afon Ystwyth, after which the town is named (Aberystwyth = ‘Mouth of the Ystwyth‘), comes into the harbour, just behind the southern harbour wall. It runs parallel to the sea for a while, separated by a spit of large fist- to football-sized pebbles. It looks, as a notice admits, a barren and lifeless environment, but is in fact a rich ecosystem and SSSI (Site of Special Scientific Interest) where {{ringed plovers nest and there is a prostrate blackthorn believed to be 200 years old.

At the end of the shingle beach the path cuts steeply up as the cliffs rise and start their long undulating journey south. The land of long sand beaches is giving way to a coast of cliffs and rocky coves.

Over the clifftop ahead I see two birds of prey, split-tailed, a brown fleck on their breasts and wings hooked back like Stukas poised to strike. They wheel and glide, their wing edges split shaggily to catch each breath of air, then, perhaps because they sense my presence, fly off inland.

A short while later I find a trail of feathers leading under a gorse bush, softer down on the far side. Was this the last struggle of a gull chick, torn from its cliff nest, then dragged in talons, like meat on a hook, to the waiting raptor brood. I imagine the parent gulls, returning to find their season’s effort squandered, their choking gullets filled with now unneeded fish, which were themselves once spawned, each another fish’s child.

A short while later I find a trail of feathers leading under a gorse bush, softer down on the far side. Was this the last struggle of a gull chick, torn from its cliff nest, then dragged in talons, like meat on a hook, to the waiting raptor brood. I imagine the parent gulls, returning to find their season’s effort squandered, their choking gullets filled with now unneeded fish, which were themselves once spawned, each another fish’s child.

Later in the day I saw another similar wheeling bird and realised the Stuka-like wings were due to a white bar under each wing, which against the sky, gave them their hooked appearance. So, I think red kites hunting along the shore … and the red kite is a symbol of the Welsh language, so fitting.

Feeding on a cereal bar and later a Snickers, I was hoping to get a breakfast at Llanrhystud, the first village the path goes through south of Aberystwyth, although it is a good ten miles distant. However, much closer the cliffs drop down into a wide valley and a large caravan site. I can see a substantial building and wonder if the clubhouse serves non-residents; perhaps I can get my breakfast earlier than midday. But the path gives the caravan site a wide berth to the landward side; clearly the caravan site does not want walkers anywhere near their land. This does seem short-sighted; either there will be so few walkers that they will not cause any nuisance, or sufficient that there is a business opportunity.

In fact, when I get to Llanrhystud, the path up to the village runs through a caravan site and past its clubhouse, which very clearly said ‘All Welcome’. However, I’d already asked a lady walking her dog, and she had told me there was a pub in the village where I could get food, so I headed on to that. I never did get to the pub, as where the path meets the main road there is a garage, shop and café, of the all day breakfast kind, where I stopped to write about the birds of prey and wrote my first poetry of the journey, “Rock“.

In fact, when I get to Llanrhystud, the path up to the village runs through a caravan site and past its clubhouse, which very clearly said ‘All Welcome’. However, I’d already asked a lady walking her dog, and she had told me there was a pub in the village where I could get food, so I headed on to that. I never did get to the pub, as where the path meets the main road there is a garage, shop and café, of the all day breakfast kind, where I stopped to write about the birds of prey and wrote my first poetry of the journey, “Rock“.

As the path rejoins the sea out of Llanrhystud, it meets a pebbly beach, where the deep rumble of wave on stone sounds like a heavy train passing in a distant tunnel. I am guessing the pebbles were transported here as sea defence to protect the low-lying farmland behind.

Anglers huddle down against the light rain, and anglers’ families huddle down beside them.

After a while the land rises once more, but only slightly, an earthy sea cliff rising a mere twenty feet or so above the waves. I see signs of sea defences, piles driven into the gravelly beach below. I understand the reason to put dykes around farmland, but here, to slow the erosion of the cliff edge, it seemed futile, and nowadays the eventual loss of land is accepted. Maybe one day the once drained low-lying farmland will also need to be ceded to the sea like the Lost Cantrefs of old.

Coming into Llansangffraid, where the church has a slate tiled wall on its east side, there are two alternatives for the Coast Path: one along the beach, and the other inland through Llannon. The notice says that the former may be impassable after wet weather, and the impassable point is where the river meets the sea at the far end from me. It also mentions shops and food in Llannon. I opt for the lower risk strategy and head inland; it is all on roads, so albeit a little longer in distance, it will probably be no longer in time.

Going through the village I spot only a butcher and music teacher. To get to the food and shops you need to go into the village and then turn back along the road in the Aberystwyth direction. Having eaten a little earlier, it didn’t matter to me, but if I had needed food, I would have had to backtrack when I got to the end of the village.

Going through the village I spot only a butcher and music teacher. To get to the food and shops you need to go into the village and then turn back along the road in the Aberystwyth direction. Having eaten a little earlier, it didn’t matter to me, but if I had needed food, I would have had to backtrack when I got to the end of the village.

There is a small estate being built where I expect the path to lie, but just before the estate is a footpath. In fact if I had waited there is a Coast Path signpost at the entrance of the road into the estate, but unsure whether the new estate has disrupted the coastal path route I follow the footpath, down beside the stream and behind the estate.

The fences of the new houses back onto the stream and I notice one of them has sacking hung down the banks. The banks of the stream are simply earth, and the fence is built on the outside of a bend, it will eventually erode, the sacking a vain attempt to hold back the inevitable. Sooner or later earth bank, garden fence and flower bed will fall into the waters. Thinking about the large tracts of housing on floodplains around the UK, now at risk with a changing climate, maybe some basic hydrology would be worthwhile in architecture courses.

The estate itself consists of pastel-coloured houses with what the estate agent described as ‘Georgian style windows and decorative bandings’; the former meant lots of square glass panels, and the latter mock stonework around windows and doorways. However, the dimensions for the windows were anything but Georgian: instead of the tall airy windows, these were short and squat, more like cottage windows than the Georgian townhouses the buildings were meant to emulate.

I thought the designers clearly knew as much about architecture as they did about river flows.

However, my judgement was, perhaps, a little premature. Later, on the approach into Aberaeron, the first terrace of houses are classic Georgian, similar colourings, and the characteristic tall windows of the period, but down the back streets, near the quay, there is a run of smaller cottages, which are Georgian in general appearance, but have squat cottage-style windows almost identical to the Llannon estate. Then as now, glass was probably more expensive than brickwork, so, at the risk of mixing a metaphor, you cut your cloth.

Returning to the coast, I see that the river would have been passable, it cuts a path through the pebbles, but has stepping-stones over it. However, I think the path literally cuts around the pebble beach, so would have been heavy going. Later, at the second-hand bookshop in Aberaeron, I hear what I think is the story for this stretch of the path. There had been a path on the top of the small grassy bank above the sea, but it was eroding and parts of the path falling into the sea. The owner of the land, a hotelkeeper, asked the council to share the costs of repairing the path, but they refused. Later when the Ceridigion Coast Path and later the Wales Coast Path sought to take more of the hotel’s land to reinstate the grassy path, the owner, not unreasonably, said "no".

Returning to the coast, I see that the river would have been passable, it cuts a path through the pebbles, but has stepping-stones over it. However, I think the path literally cuts around the pebble beach, so would have been heavy going. Later, at the second-hand bookshop in Aberaeron, I hear what I think is the story for this stretch of the path. There had been a path on the top of the small grassy bank above the sea, but it was eroding and parts of the path falling into the sea. The owner of the land, a hotelkeeper, asked the council to share the costs of repairing the path, but they refused. Later when the Ceridigion Coast Path and later the Wales Coast Path sought to take more of the hotel’s land to reinstate the grassy path, the owner, not unreasonably, said "no".

After this the path rises over another hilly section, but simply higher earthy rock, not like the hard black, up-ended strata around Aberystwyth. These cliffs are unstable, and every so often you can see where a fence has had to be remade, extending in a rough inland arc around a crumbled gulley, sometimes with the remains of old posts and barbed wire dangling down into the abyss.

Along the way there are frequent signs that say ‘cliffs can kill’, and remind you to stay on the path. They are dangerous both above, where the cliff edge is often unstable, and even more so below. I recall a year or so back a girl was killed by the South Coast Path when, after heavy rain, a portion of cliff, not unlike this, collapsed, burying her.

Turning a bend I could see down the cliffside and about six feet down, on a ledge barely the size of a table, were a sheep and a lamb. The sheep was lying down and at first I thought injured or dead, but later stood up. On the clifftop a lamb grazed on the cliff side of the fence and too late I realised I should have taken a wider path around as, on seeing me, it too jumped down the cliff to join its mother and sibling.

Although I have many photos of cliffs and sheep, I note I have none of this sheep, I guess I was too worried about it; clearly I lack the journalist’s instinct.

The only thing I could think of was to find a pub or shop in the next village, Aberarth, which was just a half mile on, and pass on a message for the farmer; I was worried that the sheep would not be noticed as it was not making any noise and only noticeable from particular angles. I couldn’t imagine how the farmer would get it up without the sheep panicking and leaping down to its death, most probably taking the farmer with it.

In Aberarth, I passed by the footbridge and went on to the main road and the road bridge, thinking I would find something there, but, whether there is a pub out of sight or Aberarth is too close to Aberaeron so doesn’t have one of its own, I certainly couldn’t spot one. With nothing else I could do I set off down the street towards the sea and then spotted a man coming out of a house.

In Aberarth, I passed by the footbridge and went on to the main road and the road bridge, thinking I would find something there, but, whether there is a pub out of sight or Aberarth is too close to Aberaeron so doesn’t have one of its own, I certainly couldn’t spot one. With nothing else I could do I set off down the street towards the sea and then spotted a man coming out of a house.

"Are you a knowledgeable man?", I said.

"I am," he replied (they don’t normally say that!).

I told him about the sheep.

"Oh, they are always doing that, its a mystery how they get there, it is fenced off and blocked at each end, maybe they get up from the beach, winter and summer. The farmer knows about it."

What had seemed to me a major rescue operation requiring at least the Fire Service, if not Mountain Rescue and Prince William in a Sea King helicopter, turns out to be everyday routine for the Welsh sheep farmer.

The final walk into Aberaeron is uneventful and eventually I am walking along streets I know well and not least the Bookworm bookshop, where I buy a map and learn about the hotelkeeper’s struggles with the council over the Coast Path, and am warned to take care on the Aberaeron to New Quay section, as it is slippery after rain.

The final walk into Aberaeron is uneventful and eventually I am walking along streets I know well and not least the Bookworm bookshop, where I buy a map and learn about the hotelkeeper’s struggles with the council over the Coast Path, and am warned to take care on the Aberaeron to New Quay section, as it is slippery after rain.

I talk with the shopkeeper about the problems of having the Coast Path through your land. Most walkers will be careful with gates, but of course it is the small proportion who aren’t who cause problems. She has a friend who has valuable horses, but finds that the gates through the land are sometimes left ajar, or dangerous litter dropped in the fields.

I wonder whether it would be possible to in some way compensate those who have footpaths through their land. Actual payments would not be possible in straitened times, but as the presence of public footpaths effectively reduces the amenity of the ownership of the land, it would seem fair to have some sort of formulaic reduction in the rateable value of the land, reducing the council taxes paid. By not being taxed and then paid, this would not increase headline public spending …, although of course would be effectively the same. It is crazy, but a part of current politics and economics, that key metrics are more important than the real underlying economy. If a privatised company borrows, it is financing growth, but if a nationally owned body does exactly the same it contributes to government deficit. The impact on the economy is, in real terms, equal, but by changing the key indicators it may affect exchange rates, and credit ratings. As I said, crazy.

And, for this day, it only remained to wait for the infrequent Sunday bus to Aberystwyth, slip down the steps there on the way back to the van, and then sore-bottomed, drive the van back to the Aeron Coast Caravan Park to spend the night.