a toll bridge with no toll, a Genoan wreck and a textile map, Mary Jones’ Bible and Jane Whittle’s gallery

12 Jun 2013: blog | flickr | audio | map | data

miles walked: 4

miles completed: 584.3

miles to go: 476

If you look on a map Barmouth to Fairbourne is just two miles, and an easy two miles too, but very lovely across the estuary-end railway bridge.

This was really a ‘finishing off’ of the day before, when I’d stopped at Barmouth because of the train times. Going out by train is no problem, but the logistics of returning by train are far more difficult; it is so hard to predict the time taken to walk along differing kinds of surface … and manage any detours or confusion along the way, and then the need to sync this with trains that run every two hours, or even, as the previous night, with a four-hour gap.

However, this was a day when I needed to move the van from its campsite at Tal-y-Bont, and also when I hoped to visit, in the van, the Dysynni Valley to find the locally produced textile map that I had read about in a 1996 Common Ground booklet ‘from place to PLACE: maps and Parish Maps‘. I also hoped to meet Jane Whittle at her gallery, an artist who was involved in the Dysynni Valley map when she moved to Wales in the 1990s.

Having parked the campervan by Barmouth Station, not a problem, but I’d guess a somewhat harder task in full season, I have an all day breakfast at Rosie’s Diner. I had seen this the day before, and had first been tempted by the large notice that read ‘Famous All Day Breakfast‘, despite its hyperbole (I’d not heard talk of Rosie’s Diner in Tiree), as any mention of ‘all day breakfast’ tends to catch my attention, but also partly eating there in honour of Rosie, the other long distance walker! Anyway I can never pass by a good ‘caf’.

Having parked the campervan by Barmouth Station, not a problem, but I’d guess a somewhat harder task in full season, I have an all day breakfast at Rosie’s Diner. I had seen this the day before, and had first been tempted by the large notice that read ‘Famous All Day Breakfast‘, despite its hyperbole (I’d not heard talk of Rosie’s Diner in Tiree), as any mention of ‘all day breakfast’ tends to catch my attention, but also partly eating there in honour of Rosie, the other long distance walker! Anyway I can never pass by a good ‘caf’.

They offer three breakfasts: a smaller one, a larger one and a ‘Belly Buster’ breakfast. If I had been doing 20 miles, I would have been tempted by the Belly Buster, but 2 miles seemed a lame excuse. However, as the larger breakfast included a pot of tea whereas the smaller did not, simple economics dictated the larger breakfast!

I head through the town streets towards the railway bridge which takes me through tiny back alleys, whereas the Coast Path stays on the prom, but both take you to the same coast road and a tiny park with a sculpture of three men tugging together on a fishing net. Bodies pressed close in joint effort, mouths gasping with the strain, the stone seems in tension. Later, looking at the photograph, I think of the disciples told, "Cast your net on the other side," and having to drag their catch ashore for fear of over-spilling their Galilean boat.

The railway bridge is a wonderful affair, the initial section, over the deepest part of the river, suspended by arches of steel, and thereafter simple piles, all supporting a wooden platform of sleepers that seems plenty strong enough for foot passengers, but hardly sufficient for a train. I do note that the train slows as it crosses the bridge. In fact the structure is cross braced, with the sleeper-like timbers running from side to side, but then the track actually sitting on two long thicker timbers that run one under each rail, so that the weight of the train is not focused on any single timber, but spread amongst the whole. I think back to the three men pulling together on the net.

The railway bridge is a wonderful affair, the initial section, over the deepest part of the river, suspended by arches of steel, and thereafter simple piles, all supporting a wooden platform of sleepers that seems plenty strong enough for foot passengers, but hardly sufficient for a train. I do note that the train slows as it crosses the bridge. In fact the structure is cross braced, with the sleeper-like timbers running from side to side, but then the track actually sitting on two long thicker timbers that run one under each rail, so that the weight of the train is not focused on any single timber, but spread amongst the whole. I think back to the three men pulling together on the net.

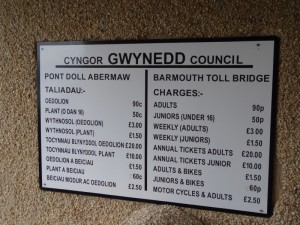

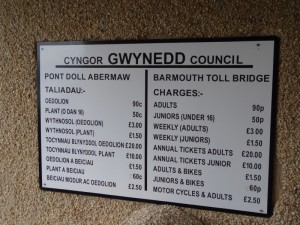

The bridge is a toll bridge for pedestrians and cyclists; cars have to go upriver to either the road toll bridge at Penmaenpool or the river bridge near Dolgellau, the reason for the importance of the town. In fact the road toll bridge only carries vehicles of 2.5 tons (or 1.5 tons, it says on the other side; surely it doesn’t matter which direction you drive in?), so when I drove to Tywyn later that day I needed to take the long route.

There are signs to say there is a toll to pay and a schedule of charges, but the toll-keeper’s window is closed. The local council pays the railway £40,000 a year as a contribution to the maintenance of the bridge to allow pedestrian access. Some of this comes direct from funds, but the rest comes from the collection of tolls. However, the couple who had been toll-keepers for many years gave up the job, and so far the council have not found a replacement, leaving a hole of £23,000 in the council finances.

There are signs to say there is a toll to pay and a schedule of charges, but the toll-keeper’s window is closed. The local council pays the railway £40,000 a year as a contribution to the maintenance of the bridge to allow pedestrian access. Some of this comes direct from funds, but the rest comes from the collection of tolls. However, the couple who had been toll-keepers for many years gave up the job, and so far the council have not found a replacement, leaving a hole of £23,000 in the council finances.

Evidently some local businesses have been in discussion about alternate uses of the toll-keepers’ cottage, and it would certainly make good sense to supplement the toll-keeping charges with a simple kiosk with cards and refreshments, as many simply walk the bridge for the views over the estuary and the experience of nearly a mile of wood-planked suspension over water. I am certain many of these would buy booklets, polystyrene cups of tea, or toy trains for children or grandchildren.

The experience was not as profound as that on the Severn Bridge, gazing across the vastness of the estuary, but the views are wonderful, and there is something so special about the combination of solidity and yet precariousness, as one steps from plank to plank.

The experience was not as profound as that on the Severn Bridge, gazing across the vastness of the estuary, but the views are wonderful, and there is something so special about the combination of solidity and yet precariousness, as one steps from plank to plank.

Beyond the bridge the path should lead along the riverside to the sea, and then along beside the Fairbourne Light Railway into Fairbourne. However, this is closed for works and the suggested alternative cuts into the hills, bypassing Fairbourne. So, instead I took the main road route into Fairbourne and seemed to survive. I was happy I had done so as I just got to Fairbourne with six minutes to spare before the train. I had been a little too leisurely with my big breakfast.

Back in Barmouth, I decide to walk along the small piece of seafront between the railway station and the bridge, partly as I had ‘missed’ this before when I walked through the back alleys, and partly because I had seen a building with ‘Bath House‘ written on it, and wondered what its story was.

Back in Barmouth, I decide to walk along the small piece of seafront between the railway station and the bridge, partly as I had ‘missed’ this before when I walked through the back alleys, and partly because I had seen a building with ‘Bath House‘ written on it, and wondered what its story was.

The Bath House, beside the quay, is clearly now a café, but a closed one, so I couldn’t go in to get a cup of tea and the story. However, I then noticed a round house, which is aptly named the ‘Round House‘ or ‘Ty Crwyn‘ and is the old town gaol constructed by the council in 1834 following a petition by the residents plagued by the ‘drunken riots’, which were a matter of ‘notoriety’. Barmouth was a major sea port at the time, filled with seamen who drink hard, and in all likelihood fight hard also. The Round House is split into two equal semi-circular cells, one for men and one for women. In the spirit of true equality, the women were no less riotous than the men.

From the Round House I see a curious sign, a handmade swinging arrow mounted on top of an orange traffic cone saying ‘shipwreck museum, free’.

From the Round House I see a curious sign, a handmade swinging arrow mounted on top of an orange traffic cone saying ‘shipwreck museum, free’.

The Shipwreck Museum is housed in Ty Gwyn, the ‘white house‘, the heart of Tudor support in north Wales, preceding Henry Tudor‘s successful campaign, which made him Henry VII and started the modern age. It was built at the water’s edge so that participants could arrive by sea for secret meetings, maybe including representatives of Henry Tudor, then in France.

The museum is not about shipwrecks in general, but the story of a single wreck discovered just off the coast, a story of marine archaeology and painstaking detective work. The wreck was in shallow waters, so the ship’s timbers had long since rotted, but metalwork was scattered widely amongst a boulder field, which made scouring the sea bed difficult for the divers. The ship’s bell was discovered, but it bore no name; there were coins, some dating back to 1500, some to the late 17th century, but of mixed origin. The cargo, however, was clearly marble, and the statue on the seafront is carved from one of the pieces recovered from the sea floor. The marble was eventually traced by its chemical analysis to a particular quarry in Carrera.

Carrera marble is the best in the world, and was used by Michelangelo, amongst others. At that time the sculptors would often travel to the quarries to select the stone to work with. I recall visiting the area many years ago when at a conference at Marina de Carrera, the port where today the Carrera marble is shipped across the world. The narrow roads zigzag their way to the ‘cava’, the individual quarries in the white hillsides. They feel precarious enough in car or bus, but the huge lorries that transport the marble cannot turn at the hairpins, and instead go forward and in reverse along alternate stretches. This will be bad enough on the way up with an empty flatbed, but perilous indeed on the way back with a 40-tonne block of marble.

Carrera marble is the best in the world, and was used by Michelangelo, amongst others. At that time the sculptors would often travel to the quarries to select the stone to work with. I recall visiting the area many years ago when at a conference at Marina de Carrera, the port where today the Carrera marble is shipped across the world. The narrow roads zigzag their way to the ‘cava’, the individual quarries in the white hillsides. They feel precarious enough in car or bus, but the huge lorries that transport the marble cannot turn at the hairpins, and instead go forward and in reverse along alternate stretches. This will be bad enough on the way up with an empty flatbed, but perilous indeed on the way back with a 40-tonne block of marble.

The cava of the marble from the wreck is no longer in operation, as the marble has all been dug out, but it was once the premium marble, the best of the best.

From this and other scraps of evidence the archaelogists surmised that the ship was Italian, maybe from Genoa, and was maybe wrecked in 1701 when a three-day storm ripped across the whole of Britain, ships and buildings alike, tearing the English fleet from its moorings on the East Coast, and driving it across the sea to Norway.

Finally in 1901 an old chart was found in an archive, with a mark, just where the wreck was found, saying, "Genoan ship wrecked here in 1701". The detective work had been right.

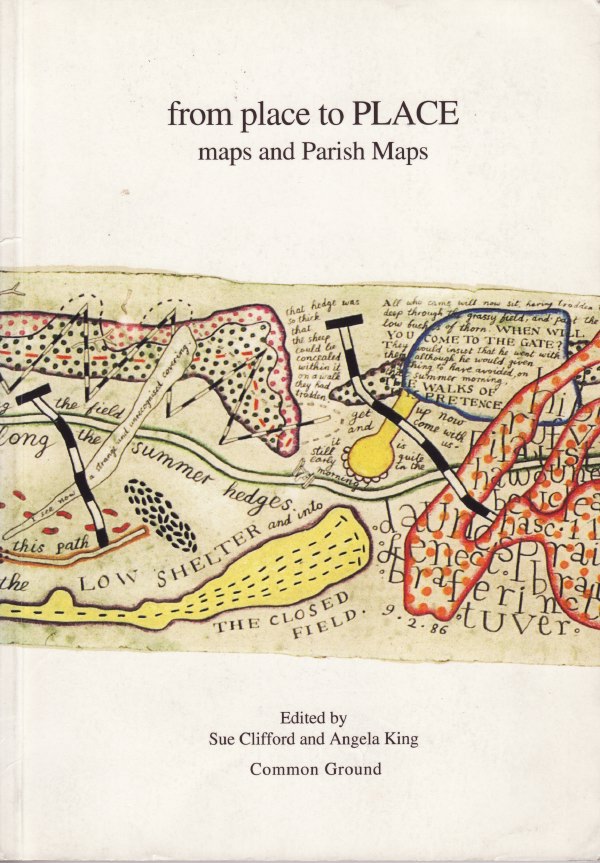

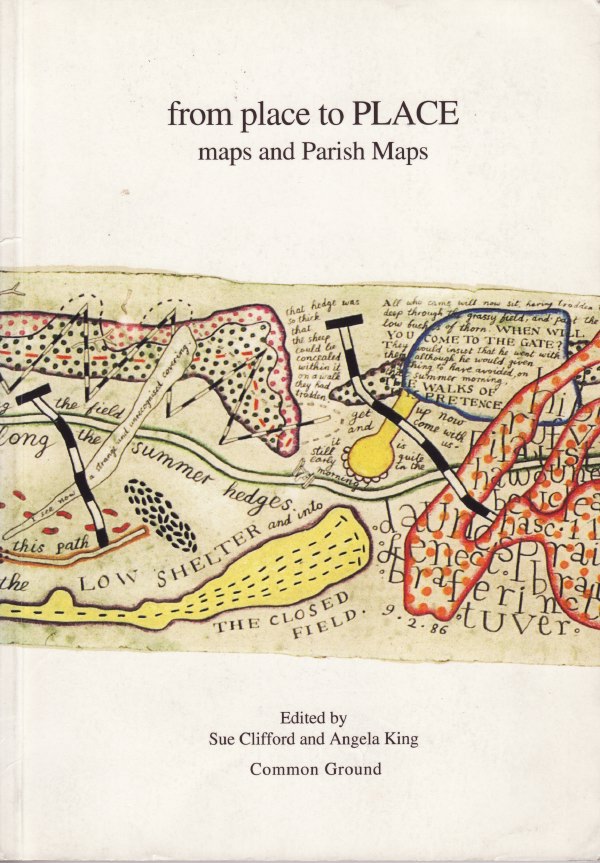

I had read about the Dysynni Map in ‘from place to PLACE: maps and Parish Maps‘ a small book reporting on Common Ground‘s Parish maps project in the 1990s. I’m not sure where I originally got the book, I assume a second-hand bookshop at some time, and I don’t recall reading it until I was starting to think about the walk and scanned my bookshelves for books on maps and found it.

I had read about the Dysynni Map in ‘from place to PLACE: maps and Parish Maps‘ a small book reporting on Common Ground‘s Parish maps project in the 1990s. I’m not sure where I originally got the book, I assume a second-hand bookshop at some time, and I don’t recall reading it until I was starting to think about the walk and scanned my bookshelves for books on maps and found it.

The Parish Maps project encouraged communities to create their own maps of their localities, using local knowledge, and in general emphasising the things that make the land meaningful to them. The Parish Maps website has a complete list of the maps created during the project, some by individual artists, some as group projects. The book consists of a series of short chapters talking about the production of some of the maps, and reflections on the project. Frustratingly, neither book nor website has many images of the maps themselves. I guess nowadays they would all be photographed for the web, but in 1996 the web had only just begun.

One chapter was by Jane Whittle, who had originally been part of a Parish Map project in the South of England, but then moved to the Dysynni Valley, so she facilitated a community map there also. The chapter said that the map had been put on permanent display at St Cadfan’s church in Tywyn. However, when I looked up the church on the web there was no mention of the map. It had been more than 15 years since the book was published, so I assumed the map had been removed, but, on a whim, I tried to look up Jane Whittle herself, and found links on several artists’ websites in west Wales, some of which included an email address, which worked!

Jane explained that St Cadfan’s church had found that the map was too popular and had it removed. This still astounds me. I can see that the church is a place of worship and prayer, not a tourist destination, but still, anything that brings people into the church, whatever their initial motivation, must be good. Happily, another church, St Michael’s in Llanfihangel-y-Pennant, at the top of the Dysynni Valley beneath Cader Idris, thought differently, and the map is now displayed there.

I had originally intended to visit Jane and see the map on a pre-walk visit to Wales, but snow had prevented that trip and so it was only now that I was able to visit. However, there were some problems. It had been several days since I’d had any internet connectivity so (1) I hadn’t been able to email Jane to say I was coming and check she was around to visit, (2) I hadn’t been able to find the email that said (2.a) where she lived and (2.b) the name and location of the church.

However, when she had originally told me about the church and given me instructions to find her, I had looked up both her gallery and the church on Google maps, so I had a rough idea of where they were.

There are only two roads up the Dysynni Valley, one to the north of the river and one to the south and I was 99% certain Jane lived just off the northern road. It couldn’t be difficult.

I turned off the A-road to Tywyn, through the village of Llanegryn, and on up the valley. I kept a look out for turnings to the left, looking for a sign to an art gallery. Eventually I got to the place where the road crossed to the river and joined the southern valley road. I had clearly missed Jane‘s gallery.

My original plan had been to see Jane first and then make my way up the road to the church. However, as I was already a substantial part of the way up the valley, I swapped destinations and kept following the road upstream. I could see the church marked on the map at Llanfihangel-y-Pennant, and while I couldn’t remember the name (my mind and names do not suit each other), it looked in the right sort of location (mind and maps work better).

The road leads beneath a spectacular craggy pinnacle, which I later learnt was called ‘Bird Rock‘ and is the only place in the UK where cormorants nest inland. Evidently the sea once stretched this far inland, and as the ancient sea levels dropped, the cormorants ended up flying further and further to get to the sea, but stayed nesting on the old cliff face.

Eventually there is a branching of the ways, the larger road heads over the mountain pass to Tal-y-Llyn, while I took a narrow, single-track road towards Llanfihangel-y-Pennant.

On Tiree and in many places in the west of Scotland and the Isles, the roads are all single track, but they have well-marked passing places every hundred yards or so. However, this very sensible style of road is not followed in other parts of the UK. I know from past experience that when I am driving a large campervan and meet a small hatchback in a country road, the car driver almost invariable freezes and I have to do the reversing. I have no idea what happens when two hatchbacks meet along one of these roads, I can only assume that they stay there forever frozen, like Sirius; Zeus presumably thought that, in our mechanical days, he had seen the last of uncatchable foxes being pursued by inescapable hounds, but then came the irreversible hatchback and the single-track road.

As I drove along I kept track of every driveway, or slight widening of the road, in case I was called upon to back along the road to the closest place to pass. The road got ever narrower, and as each bend passed without either tractor or, heaven forbid, hatchback approaching in the other direction, my mind turned more and more to the fact that at some stage I would need to turn round.

And then it happened, a small church rose up over the wall on the left and opposite it an equally small and empty car park. I parked, but not before turning the van and making sure I was positioned so that I could drive straight out down the road back. In a campervan you soon learn that parking is often not the problem, but rather getting out after other cars have parked inches from you in all directions.

And then it happened, a small church rose up over the wall on the left and opposite it an equally small and empty car park. I parked, but not before turning the van and making sure I was positioned so that I could drive straight out down the road back. In a campervan you soon learn that parking is often not the problem, but rather getting out after other cars have parked inches from you in all directions.

St Michael’s sits low, its grey stone hunkered down amongst the bleak drizzle-damped hillside, an open bell its vestigial tower. The lych gate is equally squat and solid and in the churchyard a stone slab sits supported on two pillars, some sort of cromlech-like memorial.

Inside the church a notice directs you to a vestibule on the far side of the church and there the map lies in an acrylic case. I had expected it to be hung on the wall, and had not realised that it was a deep contour map, built, I later learnt, over polystyrene layers, hand-traced, scaled and cut from the contour lines of the OS map of the valley.

Inside the church a notice directs you to a vestibule on the far side of the church and there the map lies in an acrylic case. I had expected it to be hung on the wall, and had not realised that it was a deep contour map, built, I later learnt, over polystyrene layers, hand-traced, scaled and cut from the contour lines of the OS map of the valley.

It was also huge, filling the length of the vestibule, perhaps seven or eight foot end to end and three foot wide.

The porch roof was some sort of soft lime-wash plaster that scattered gritty layers over the horizontal surface of the acrylic box, so I returned to the van to fetch my dustpan and brush for a little impromptu church cleaning. I keep them in the van to occasionally clean it during my journeys, and, being only a little over halfway round and long before Fiona would be visiting me, it was so far unused.

I had been hoping to be able to make a navigable map of the valley using the textile map as a backdrop, but, even swept of its plaster coating the low-light reflections on the acrylic made the map impossible to photograph clearly. So you will have to believe me that it is wonderful and go see it yourself. Every field and hedge is lovingly rendered in stitch and thread.

I had been hoping to be able to make a navigable map of the valley using the textile map as a backdrop, but, even swept of its plaster coating the low-light reflections on the acrylic made the map impossible to photograph clearly. So you will have to believe me that it is wonderful and go see it yourself. Every field and hedge is lovingly rendered in stitch and thread.

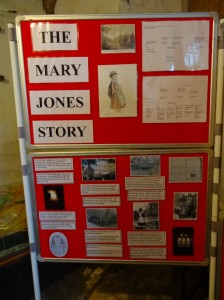

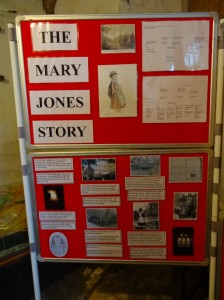

I had gone to the church to find the map, but I hadn’t realised that there was also an exhibition about Mary Jones as this was the church where she was baptised, and this is the area from which she set off to walk across the mountains to Bala.

Now, if you are from Wales you will have been brought up with the story of Mary Jones, and I know it permeated as far north as Carlisle where Fiona also heard it as a child.

Now, if you are from Wales you will have been brought up with the story of Mary Jones, and I know it permeated as far north as Carlisle where Fiona also heard it as a child.

Mary Jones was born at the end of the 18th century, and her father died when she was just four. When she was just nine, a preacher visited, Thomas Charles, who had a Welsh Bible. Mary asked how much it would cost to have a Welsh Bible of her own. The answer, three shillings and sixpence, seemed a fortune to Mary, but she decided it was what she wanted, so for six years she did jobs for people and saved, occasionally going to the house of a woman two miles away who would let Mary learn to read her Welsh Bible.

Eventually, when she was 15 years old, Mary Jones had saved enough and walked the 25 miles over the mountain to Bala where Thomas Charles lived. Charles‘ heart was moved by the girl who had worked so hard and walked barefoot over mountains to be able to read the Bible in her own tongue. Spurred by the example of this young woman, he founded the British and Foreign Bible Society to make the Bible available across the world to people in their own language, starting with a translation into Mohawk in 1804.

The exhibition at St Michael’s is quite small, but next year the Bible Society are opening a new visitor centre in Bala.

Although I knew the story well, still I found myself moved by it, just as Thomas Charles had been 200 years ago.

I was glad I had manoeuvred the van before going into the church as by the time I left other cars had come to the small car park, and as I drove away I passed two or three vehicles coming in the opposite direction. Happily each meeting was at a wider section of road, so Zeus was saved from having to cast us up as new constellations in the heavens.

I was determined not to miss Jane‘s gallery on the return down the valley, and even took the second route through the village of Llanegryn, which I was certain was too close to the main road, but thought I should check just in case. This secondary route was so steep and narrow that it almost required Olympian assistance to negotiate, but all to no avail.

Again, although I was convinced that Jane‘s gallery had been off the road on the north side of the valley, just in case I also drove up the southern road. Partway along this road I spotted a man out walking and stopped to see if he was local. He was, and he knew Jane. He told me where to look on the original road, and he also explained that she had no sign, hence my inability to find it.

Aided by these instructions I found what appeared to be the right gate, which, as warned, led up a rough track through fields. I walked up the track, not wishing to risk the van’s suspension unless I was sure I was going to the right place. It led to a small group of houses, which I assume once was a single farmstead, and sure enough, in a corner of the yard was a sign that said ‘gallery’. Beside it was a cottage with a curtained and lighted window through which the occasional sound of what I took to be radio emerged.

I knocked; I waited; no answer.

I find the process of knocking on a door or ringing someone up hard at the best of times, but this was now early evening and I was knocking on the door of a stranger who was not expecting me. I waited a few moments, and then summoned up my courage.

I knocked again; I waited; no answer.

I stood back, looked around, checked that there were no other entrances. There was a car parked, but maybe she had another vehicle and had simply left the radio on when she left. Convinced now that my efforts were in vain, I was about to give up, but then thought, "one more time".

I knocked a third time.

In some way this last knock was easiest, as I had by now decided there was no one there to hear.

But instead, almost instantly, I heard shuffling sounds and then the door opened.

"Hello, I’m Alan", I said, as if that explained everything, "we mailed about the map".

I can’t imagine what went through Jane‘s head in those few moments. When she wrote the chapter in themid-1990s it was after retiring out here, to the wilds of West Wales; now, nearly twenty years later, she must be into her late 70s. Then here, on her doorstep, a man arrives with unkempt hair, bare-kneed and sandalled.

Maybe for an artist this is less disconcerting than for the average elderly lady, but Jane took it in her stride and invited me into her cottage kitchen with the Aga burning and a cat wandering from surface to surface.

She offered me tea, and while the kettle boiled I jogged back down the track to drive the van up as it was parked dangerously close to the bend. I drove carefully through the gateway to her yard, just a few inches either side. The yard was quite small, and after a failed attempt to turn round I realised that getting out was going to entail reversing through the same tight gateway.

She offered me tea, and while the kettle boiled I jogged back down the track to drive the van up as it was parked dangerously close to the bend. I drove carefully through the gateway to her yard, just a few inches either side. The yard was quite small, and after a failed attempt to turn round I realised that getting out was going to entail reversing through the same tight gateway.

However, there was a cup of tea to hand now, and we introduced ourselves to each other and began to chat before Jane took me over to see her gallery.

Jane‘s gallery is a wonderland; just stepping through the door my jaw dropped. It is mostly her own work, but with some work of other artists also. It is in a converted cow shed, only it has not been converted much, the old stalls are still in place and each one creates a frame for a group of pictures and ceramics. Above your head, dresses are suspended from the roof beams like swooping angels, and at the far end a red dragon fills the rafters from wall to wall.

Everything seems to have a story, the dresses left behind after an exhibition, and a stained glass in the window because her neighbours have a hot tub where they skinny dip, and it is there to protect their blushes, and those of Jane’s visitors. The dragon is a longer tale.

In the Dysynni Valley is Bird Rock, a sheer rocky hill with a craggy rounded top and a slight hook, rather like the second horn of a rhinoceros. It is the only place in Britain where cormorants nest inland, still remembering the time when the sea lapped the bottom of Bird Rock, rather like the salmon recall when Europe and America were close and still make their five-thousand-mile journey to lands that were once close.

Jane‘s grandchildren would visit each summer, and made pterodactyls, inspired by the cormorant’s primeval outline as it spreads its wings. One year, one of them decided, "I want to make a pterodactyl with a 20-foot wingspan". He made the first wing, and then hoped Jane would be a good grandma and complete the second, but instead in the future years she helped him finish the huge red dragon that swoops above the visitors to her gallery.

Jane‘s own work is in a variety of media, but the majority uses torn coloured paper, glued to canvas to make pictures that at first glance look like bold oils and then the texture of the paper gradually reveals itself as you look closer. However, she also seems to use whatever materials make sense for what she is creating. There is a sculptural group of carbonised lemons, I assume simply left in the Aga hot oven for a long time, and a second carbonised vegetable or fruit, which clearly burst as it heated, as it now looks like a cracked raku bowl with a small black lid.

However my favourite work, which took my breath away, is landscape, rather like the Dysynni map, but made like a quilt over a sleeping woman. Jane had earlier described how as a child she had played on the hills and valleys of her own quilt, just like Robert Louis Stevenson before her, and that this had been an influence in the Dysynni map.

Jane told me about the making of the map, the way each person took an area and studied it, walking the ground, and then reproducing features based on a large-scale OS map. Then, when the map was launched, they placed an small errata book where local farmers could write down where gateways and hedges had moved since the OS surveys on which the map was based. I’m not sure whether this led to re-stitching before the map was displayed.

A neighbour of Jane‘s was preparing for a huge house party to arrive the following day, and invited Jane and I to an impromptu dinner, combining the spare ingredients of both their kitchens. I was never quite sure whether she approved of me, this ragged itinerant who had turned up, unannounced, at Jane‘s door, and our politics were clearly not completely aligned. However, she welcomed me regardless and it was fascinating hearing some of her experience both in a senior position at a major retailer and as a school governor.

Jane and I had a final nightcap at her kitchen table before I retired to my van in the yard ready for an early start in the morning to catch the train at Tywyn.

Sated, I pass a lovely community history mosaic and a carved dolphin overlooking the sea, before taking the steep lane up to Parcllyn, the top part of which seems to be public housing for the military base. Partway up I stop to photograph an old sports car, I think maybe an MG, with its bonnet a different colour to the rest of the car, when its owner emerges from the shed, a rusty engine part in his hands.

Sated, I pass a lovely community history mosaic and a carved dolphin overlooking the sea, before taking the steep lane up to Parcllyn, the top part of which seems to be public housing for the military base. Partway up I stop to photograph an old sports car, I think maybe an MG, with its bonnet a different colour to the rest of the car, when its owner emerges from the shed, a rusty engine part in his hands. The path skirts the base and as I go around I take photographs, both of the radar tower on the base and also the houses opposite, the missile at the entrance and a disused public toilet that is up for sale as a building plot. I wonder what the CCTV cameras make of this long-haired itinerant alternately marching at high speed along the road and then taking photos of the base.

The path skirts the base and as I go around I take photographs, both of the radar tower on the base and also the houses opposite, the missile at the entrance and a disused public toilet that is up for sale as a building plot. I wonder what the CCTV cameras make of this long-haired itinerant alternately marching at high speed along the road and then taking photos of the base. He tells me a bit about the area: first that this had been a major area for Free Wales Army support, although he had never seen the curious flag of the red Welsh dragon on black background that I’d seen a few times on Llŷn.

He tells me a bit about the area: first that this had been a major area for Free Wales Army support, although he had never seen the curious flag of the red Welsh dragon on black background that I’d seen a few times on Llŷn. Mwnt is named after the conical rocky hill (mount/mwnt) that rises 250 feet from an otherwise low and flat river valley that cuts a wide swathe through the low cliffs north and south. In the lee of the hill is a small white church dedicated to the Cross, ‘Eglwys y Gros‘. Evidently the rare dedication to the Cross suggests that its origins are even older then the building there today, dating back to the seventh or even fifth century. Certainly it was a major stopping point on pilgrim routes.

Mwnt is named after the conical rocky hill (mount/mwnt) that rises 250 feet from an otherwise low and flat river valley that cuts a wide swathe through the low cliffs north and south. In the lee of the hill is a small white church dedicated to the Cross, ‘Eglwys y Gros‘. Evidently the rare dedication to the Cross suggests that its origins are even older then the building there today, dating back to the seventh or even fifth century. Certainly it was a major stopping point on pilgrim routes. Carrying a takeaway tea from the small shop and kiosk at Mwnt, I continue along the cliff at, but soon turn inland. The original Ceredigion Coast Path along the cliff has been closed because, according to a notice, it is ‘illegally close to the cliff edge’. However, I am later told that this is more due to a landowner who doesn’t really want the path and uses safety as an excuse. However, cliff paths can be dangerous, or as the frequent notices say ‘Cliffs can Kill’, as only recently a woman fell to her death near Mwnt. I didn’t notice any particularly dangerous parts on the main path, but the rocks around are sloping and many smaller paths cut close to the edge. Over much of this coast there is a layer of soft, probably glacial moraine material, overlaying the harder rock below. The layer of soil and soft rock can easily break, and the edges, which may look secure, can easily shear off, like the snowy overhanging edges that form on mountain arêtes.

Carrying a takeaway tea from the small shop and kiosk at Mwnt, I continue along the cliff at, but soon turn inland. The original Ceredigion Coast Path along the cliff has been closed because, according to a notice, it is ‘illegally close to the cliff edge’. However, I am later told that this is more due to a landowner who doesn’t really want the path and uses safety as an excuse. However, cliff paths can be dangerous, or as the frequent notices say ‘Cliffs can Kill’, as only recently a woman fell to her death near Mwnt. I didn’t notice any particularly dangerous parts on the main path, but the rocks around are sloping and many smaller paths cut close to the edge. Over much of this coast there is a layer of soft, probably glacial moraine material, overlaying the harder rock below. The layer of soil and soft rock can easily break, and the edges, which may look secure, can easily shear off, like the snowy overhanging edges that form on mountain arêtes. The last section between Gwbert and Cardigan is back to fields and farm tracks, passing fields of leeks, some under thin plastic covers and already big enough to eat, others planted in the open ground and much smaller. I recall just a few days ago, on a more exposed piece of coast, seeing a field of leeks under plastic, but it was far less developed, maybe just the more exposed location, or maybe to do with planting time. When I say plastic, I mean the kind that rises with the crop and then decays in the sun. I recall, when I worked at the agricultural engineering institute at Silsoe, that this use of plastics was just beginning, I think at that stage more with opaque black plastics to act as a weed suppressing mulch and to warm the ground for crops like potatoes. For the leeks, you could see on the less developed field that the leek seeds or plantlets had been directly sown through the plastic, above each leek a small slit, some with the leek already pushing through.

The last section between Gwbert and Cardigan is back to fields and farm tracks, passing fields of leeks, some under thin plastic covers and already big enough to eat, others planted in the open ground and much smaller. I recall just a few days ago, on a more exposed piece of coast, seeing a field of leeks under plastic, but it was far less developed, maybe just the more exposed location, or maybe to do with planting time. When I say plastic, I mean the kind that rises with the crop and then decays in the sun. I recall, when I worked at the agricultural engineering institute at Silsoe, that this use of plastics was just beginning, I think at that stage more with opaque black plastics to act as a weed suppressing mulch and to warm the ground for crops like potatoes. For the leeks, you could see on the less developed field that the leek seeds or plantlets had been directly sown through the plastic, above each leek a small slit, some with the leek already pushing through. It seems Johnny Depp inhabits this landscape: just a short way further I expect him to appear, charming and just a little dangerous looking, as a junk-like river-boat appears. I feel I have been transported into ‘Chocolat‘. It is an Indian restaurant; what an evening out.

It seems Johnny Depp inhabits this landscape: just a short way further I expect him to appear, charming and just a little dangerous looking, as a junk-like river-boat appears. I feel I have been transported into ‘Chocolat‘. It is an Indian restaurant; what an evening out.