I woke to the sound of wind-buffeted rain hitting the campervan. I put off starting as long as possible, but eventually could think of no more excuses not to start.

It was wet, hard, driving rain that stung your face, but to be fair, this is the first really wet day since I started, and even today the rain cleared towards the afternoon, with the sun breaking some setting light below the clouds.

It was wet, hard, driving rain that stung your face, but to be fair, this is the first really wet day since I started, and even today the rain cleared towards the afternoon, with the sun breaking some setting light below the clouds.

Because of the rain, few photographs, and only one, belated, audio blog, and in many ways an uneventful day, in fact possibly the most interesting part was the taxi drive to Church Bay.

As we drove along the taxi driver said he was hoping for fine weather the following weekend as he and some friends were planning a golfing trip to Bethesda, but he couldn’t play in the rain as he didn’t have waterproof golfing clothes. He explained how difficult it was to get clothes, but in particular waterproof clothes, when you are a large size. The major outdoors shops stock up to 2X, but not the 4X or 5X that the taxi driver needed.

During the walk I have complained, especially on audio blog, about parts that are wet, muddy or hard to navigate. For the hardened hiker these are normal things to expect, but the aspiration of the Wales Coast Path is, I believe, wider, to get ordinary people walking. Imagine you are not used to walking, and then, with your family, you decide to follow a part of the Coast Path, but then you get lost or sink to your knees in mud; you may never venture out again.

During the walk I have complained, especially on audio blog, about parts that are wet, muddy or hard to navigate. For the hardened hiker these are normal things to expect, but the aspiration of the Wales Coast Path is, I believe, wider, to get ordinary people walking. Imagine you are not used to walking, and then, with your family, you decide to follow a part of the Coast Path, but then you get lost or sink to your knees in mud; you may never venture out again.

Equally, if you are overweight, then walking is an excellent way to burn off some pounds and make you generally more healthy. The taxi driver wanted to do precisely that, but could not get clothes in a suitable size, so, if the day looks wet, will not walk or play golf.

In many ways the Coast Path just south of Church Bay is similar to the path north, narrow cliff-edge pathways interspersed with green trodden routes over grassy clifftops. However, the cliffs are lower, maybe 30 feet at most, and successively lower the further south you get. Also the luxuriant tumbling flowers are less evident, maybe because the brambles are covering the cliff edges.

I was glad I’d worn boots, but the puddles were more from the rainfall, the path itself did not seem intrinsically muddy, and the cliff-edge parts of the path are high-edged with bramble and gorse, so all in all it feels a good part for a family walk, although I’d keep a hand on small children anywhere on the Coast Path.

The map says there is a fort at the southern end of Porth Trefadog, but I didn’t notice that; however, at the north end of Porth Trefadog, up dry on the headland, is the hulk of an old wide-keeled timber ship.

A little further on, at Tywyn Hir, there is a massive caravan site. Those near the sea have timber decking, with glass sheets on the seaward side, so that they can sit and watch the sea, but protected from the worst of the elements. I spot a chiminea on one of these timber patios. As I walk by one caravan, a woman comes out with the most wonderful cascade of dark glistening dreadlocks, starting at a sort of top-knot and then falling down her whole back. She goes round to the side of the caravan, opens a small timber garden store and inside, instead of a lawnmower or garden chairs, are a washing machine and tumble drier. "We call it home from home", she says. I wonder again about these caravan communities, and recall a friend at junior school who always went on about ‘Swanage‘ where his family had a caravan. Roads were slower then, and Swanage a long way from Cardiff, so I guess they spent less time there than the modern caravan dweller, but I guess not so different 40 years on1.

South of the caravan site, the path runs for a while on roads and lanes, with occasional stretches on the beach, albeit, with wind driven waves, at times perilously close to getting my feet wet. At one point there is a small bouquet on the road side. There is no message, but I assume someone drowned here once and is still remembered.

In one stretch along the top of the beach at Traeth y Gribin, I walked on the sand and must have missed a crucial sign. The path cuts round a point to follow the edge of the estuary of the Afon Alaw. I thought the going was maybe a little tough over shingle and river mud, but it was when I realised I was, first, the wrong side of a salt marsh with muddy rivulets running through it, and then the river side of a barbed wire fence, that I became certain I should be on the landward side.

Happily I was able to get onto the path proper not too far upstream and without any serious foot wetting. This was close to the point where the river is still tidal, but clearly more fresh than salt water as the tideline was thick with decaying grass, with very little seaweed. However, I then noticed that what I had taken for foam, or small stones amongst the sandy damp grass, was in fact thousands of small dead crabs, most barely an inch across, like pirate doubloons cast along the shore.

On the map it marks two possible routes, one crossing the Afon Alaw, and the other going inland to Llanfachraeth as, at the time the map was made, the intended river bridge had not yet been constructed. As I came along the river, the new bridge was there, a green arc across the waters, a flock of swans having a tête-à-tecirc;te at the far side. However, the bridge was also full of bright orange building barriers, and evidently still under construction.

Happily, as I came to it, I found the bridge was indeed open, albeit with barriers covering parts of the bridge where the safety railings had not yet been installed. One had been blown adrift but I was able to do my Bob-the-Builder good deed of the day and put it back in position.

Happily, as I came to it, I found the bridge was indeed open, albeit with barriers covering parts of the bridge where the safety railings had not yet been installed. One had been blown adrift but I was able to do my Bob-the-Builder good deed of the day and put it back in position.

I was glad of the extra mile or two that the bridge saved, but a little disappointed that I didn’t get to Llanfachraeth and a short rest, food and a pint!

On the south side of the river there is no danger of getting the wrong path as it is mostly fenced on both sides, with timber staging over the (most) muddy parts. This, like the bridge, is all new and still under construction. While I complain sometimes at Anglesey‘s path signage, it is clear they are investing in the path. At one point I see a sign, ‘use it or lose it’, warning of the council’s intention to close a footpath. It may be that the path being closed is because the coastal path is creating an alternative access, or maybe a deal with the landowner, "you let us have the coastal path, and we’ll get rid of this awkward path". The tenor of the community notice suggests the latter. Certainly the council’s own notice advertising the closure is well off the line of the path and can only be approached by clambering over old wire netting … open government?

After clearing the river estuary there is a short stretch on the beach, at the end of which a Coast Path sign points you up some steps and onto the road. If the tide is low ignore it. Having missed the signposting before, I followed the signs, but these take you on the alternative, high-tide route along roads on the south east of the Newlands Park estate, rather than along the water’s edge. However, both take you to the causeway linking Holy Island to the mainland of Anglesey. The causeway, like the Menai suspension bridge, is another of Telford‘s engineering achievements.

At the beginning of the causeway a sign points you to the left, across the railway and under the second (later) causeway, but this is an alternative coast route that bypasses Holyhead and Holy Island. So if you want to ‘do’ Holy Island, ignore this and head over towards the chimney of the aluminium works.

Part way across the causeway a sluice gate allows the tidal water to flood through, and I wonder at the sheer power of tides and imagine a turbine spinning in the rushing waters.

From the causeway and further along towards Holyhead, I occasionally spot what I take to be cockle pickers, out with bucket, fork and hook, turning over seaweed, digging into the soft mud.

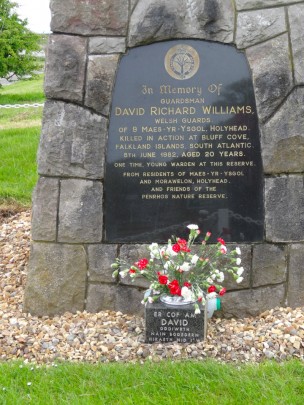

Beyond the causeway, the path takes you through the coastal park, set up on the unused land owned by the aluminium works. I see notices describing a new leisure village to be constructed between the coastal path and the works. The latter is now closed, its chimney stack no longer spewing white smoke, and a sorely missed employer in the area. You follow along the water edge, past a memorial to a soldier, who used to be a volunteer warden, lost in the Falklands, through flower-filled woods and a tranquil pet cemetery, then across grassy fields until Holyhead port draws close.

The last landmark before getting into the port and railway station is the Skinner monument. Climbing up some steps and a small slope gives you a panoramic view over Holyhead. Then back at the bottom you can read about the story of John MacGregor Skinner, Captain of the Holyhead Mail packet and benefactor of the town. He was born in New Jersey, where his father organised the Royalist militia when the American War of ‘Independence’ broke out in 1776. His family, being on the losing side, scattered, some to Canada, and some to Britain.

It is a reminder that the American wars are somewhat misnamed. The first war was as much a civil war between different factions within the (now) US as a war of secession from Britain. The ‘Casus Belli‘ was partly tax avoidance, but also about preserving slavery, which Britain was moving against, and the British government‘s annoying habit of blocking the seizing of native American lands. The second, misnamed ‘Civil War‘, was in fact the actual war of independence when the southern states attempted to leave the ostensible free federation of states and were crushed.

As I finally drew into Holyhead railway station, I was very glad of that bridge over the Afon Alaw as I arrived just half an hour before the last train back to Rhosneigr where I was camped.

- Later in the walk I realised this must have been ‘Swanbridge‘ a camp site just a few miles west of Cardiff.[back]

Too soon I have to take my leave as I need to get up to

Too soon I have to take my leave as I need to get up to