I knew it would be a tough day, sixteen and half miles from Porth-y-Waen to Trevor and then another four from there to Llangollen. I’d decided that if I didn’t get to Trevor early enough I’d just take a taxi on to Llangollen, but really didn’t want to do that otherwise I would get more behind for next week.

The day started fairly leisurely, along lanes into Nant-mawr and up over the first hill of the day towards Trefonen. The ascent passes through Jones’ Rough, old yew woodland, with a thick darkness below, and then into more ordinary woodland before breaking the treeline onto the top of Moelydd, just 285 metres (800 feet), but one of the highest points for many miles, with a panoramic view that takes in the Wrekin and Long Mynd on one side and on a clear day even Cader Idris and Snowdonia. I forget sometimes just how narrow this part of Wales is. I am still standing in Shropshire, indeed far enough from the border that it does not appear on the Harvey strip map, but no more than 40 miles to the coast. There is one of those round plaques showing the landscape silhouette and allowing me to identify the peaks I see. Almost due north it says ‘Liverpool‘ – I wave to Esther and go on.

The day started fairly leisurely, along lanes into Nant-mawr and up over the first hill of the day towards Trefonen. The ascent passes through Jones’ Rough, old yew woodland, with a thick darkness below, and then into more ordinary woodland before breaking the treeline onto the top of Moelydd, just 285 metres (800 feet), but one of the highest points for many miles, with a panoramic view that takes in the Wrekin and Long Mynd on one side and on a clear day even Cader Idris and Snowdonia. I forget sometimes just how narrow this part of Wales is. I am still standing in Shropshire, indeed far enough from the border that it does not appear on the Harvey strip map, but no more than 40 miles to the coast. There is one of those round plaques showing the landscape silhouette and allowing me to identify the peaks I see. Almost due north it says ‘Liverpool‘ – I wave to Esther and go on.

The hillside soil here is the colour of old red sandstone. I’ve not noticed any outcrops, so assume it is more that the same processes that produced old red sandstone work here, probably simply iron salts. The path across the last long field into Trefonen follows a wide shallow tree-dotted ditch, according to the map not part of Offa’s Dyke, but maybe simply just an old trackway out of the village.

I have a moment of confusion at the end of the field as I’d been walking the right hand side of the ditch and from there the stile ahead is hidden by hedgerow, but as I cross the ditch the way ahead is clear and I meet another walker, going in the same direction, but only as far as Chirk, where I am hoping for mid-afternoon tea at the castle café. He is an experienced walker including many of the Scottish long-distance walks, and has a backpack, little larger than my day pack, but it’s his complete kit … I have much to learn.

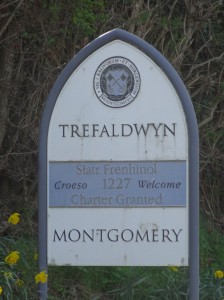

At Trefonen I pop into the small post office to get provisions for the day and see signs for the walking festival that I’d been told about over breakfast. I was also told something in the Forden pub about a brewery here, and maybe later in the day would have sought out a quick afternoon half-pint of their brew, but as it was the closest I get is walking down a road called ‘Malthouse Lane‘.

The path then cuts across farmland through the tiny hamlet of Tyn-y-Coed, where the windowsills of a shed are decorated with ceramic heads, the result of a school project some years earlier. The dyke rises steeply through woods, before levelling, tracking the ridge line for a mile or two. When the path next breaks out of the trees it is into a large grassy clearing with stone work 100 yards or so ahead; the ruins, I assume of yet another Marches castle.

The path then cuts across farmland through the tiny hamlet of Tyn-y-Coed, where the windowsills of a shed are decorated with ceramic heads, the result of a school project some years earlier. The dyke rises steeply through woods, before levelling, tracking the ridge line for a mile or two. When the path next breaks out of the trees it is into a large grassy clearing with stone work 100 yards or so ahead; the ruins, I assume of yet another Marches castle.

Before the ruins lies a sculpture, two horses’ heads with a saddle between where their necks should have been, a sort of extreme equine push-me-pull-you. There is no plaque of explanation. However, making my way across the grass, I find the castle-like ruins are in fact the remains of the grandstand for the old Oswestry racecourse which encircled the hilltop. I don’t know the age of this, but I imagine Jane Austen-like characters, coming up the steep road from Oswestry in their carriages, to watch top-hatted riders gallop high above the surrounding land, as if they were racing round the very horizon itself. Nowadays the hilltop is almost entirely surrounded by trees with scrub-trees on the racecourse common, so only another panorama plaque gives a hint as to the Regency and Victorian vistas.

Following the line of the racecourse, I took care, as I’d been warned, not to follow the footpath sign that turns right and the road, which would ultimately lead back to the grandstand, but straight on, past the second part of the racecourse, which has an almost figure of eight plan narrowing in the middle, to follow the lines of a slight double hilltop.

The route cuts down the hill and then follows the Dyke straight to Craignant, but before doing so rises up once more over what I only notice later is a much higher hill, Selattyn Hill, at 375 metres (a mountain in old money).

By this stage I am tired, following the top of Offa’s Dyke gives a great sense of connection to the past, but, like the woodland paths, the tree roots and stones make it hard going, your feet twisting at each step, my little toes that constantly have small blisters, suffer each time my foot catches on a root or rock and somewhere along the way a small stone is under the ball of my foot that for some reason I didn’t manage to shift when I shook my boots out at the grandstand.

By this stage I am tired, following the top of Offa’s Dyke gives a great sense of connection to the past, but, like the woodland paths, the tree roots and stones make it hard going, your feet twisting at each step, my little toes that constantly have small blisters, suffer each time my foot catches on a root or rock and somewhere along the way a small stone is under the ball of my foot that for some reason I didn’t manage to shift when I shook my boots out at the grandstand.

I promise myself I will shake out my boots at Chirk, just the other side of Craignant, get tea, food, so just have to keep on going one steep drop into Craignant and the climb beyond.

Then I fell.

Nothing spectacular, just caught my right foot on a protruding rock and tipped head over heels along the dyke top. Dusting myself off and happily with no harm to show except a few grazes and a bruised pride, I sit myself down and realise my clumsiness and fatigue are partly due to dropping blood sugar and, as important, not drinking enough. I never notice myself getting hungry, but need to look out for that slight clumsiness that means I should eat and drink.

I empty my boots again and discover the small stone in my boot is no stone, but my foot, a small hard swollen blister. I also refold the map, a symbolic moment, as this is now on the last quarter of the Harvey map for Offa’s Dyke. However, I also realise that I’d lost track of which village is which, that Chirk Castle is not immediately beyond Craignant, but a whole hillside and valley beyond. A Marathon bar and drink of water help, but suddenly the day seems longer.

I skip the opportunity to take a diversion to see a small hillfort and tower, pressing on as time is short and I have many miles to go, down past Craignant and steeply up, up the hillside beyond, at that point where I think it would be good, like the gentleman I passed earlier, to be ending my day at Chirk, and start to re-plan assuming I will get no further than Trevor. The day becomes one of survival, even getting that far.

Over the rise of the 361-metre hill beyond Craignant I catch my first glimpse of Chirk Castle. I had imagined seeing a few tattered battlements, but it looks large and imposing still, guarding over the Ceiriog valley, the rich farmland beyond and the route north–south. Today the floodplain of the Ceiriog is home to a large works belching out white smoke, but, more picturesque, a canal aqueduct and train viaduct cut across the valley in the distance, and beyond them the bridge of the modern road, three generations of transport.

Dropping down and across the River Ceiriog I follow the Offa’s Dyke footpath signs back up a steep road past forest to the right, and only too late realise I am following the year-long path, but it is the summer-only route that I meant to follow, up through the parklands to Chirk Castle, so no tea and cake below the battlements for me. At the top I instead take my second Marathon bar, another sip of water and start to plod painfully down towards the built up areas of Froncysyllte and Trevor below, with the estates of Cefn Mawr most apparent sprawling across the hillside opposite.

It feels late already, the day had been cloud covered for many hours, and darkening as the clouds thickened, the occasional stray droplet of rain and dark edges suggesting that tomorrow’s gales and rain may start tonight. I pass a pair of walkers putting waterproof covers over their rucksacks.

At the base of the hill the path crosses the main road and then over a small canal bridge to join the canal towpath for the rest of the way past Froncysyllte into Trevor … but, on the map, I can see an ominous steep descent to the valley base and rise between the two. The towpath is metalled and level, and I find that, sore feet not withstanding, I still walk far faster than a canal boat. After a mile or so there are two Offa’s Dyke arrows. One points across the canal to the left, but the other continues along it and says ‘Pontcysyllte Aqueduct‘. On the map I couldn’t see the path crossing the aqueduct, but assumed there must be a way ahead, maybe dropping down just before it to rejoin the other path. However, joy of joys, when I got to the aqueduct, indeed one can walk across … on the level … all the way to Trevor.

This is probably not a route for the nervous. The footpath side of the aqueduct has a balustrade, but is narrow, with the canal beside you, yet not so narrow that some cyclists ride across, only dismounting at the last moment before they pass you. I find that even when I stop to take a photograph and turn, I have a moment when my eyes and feet try to make sense of the lack of ground-line.

This is probably not a route for the nervous. The footpath side of the aqueduct has a balustrade, but is narrow, with the canal beside you, yet not so narrow that some cyclists ride across, only dismounting at the last moment before they pass you. I find that even when I stop to take a photograph and turn, I have a moment when my eyes and feet try to make sense of the lack of ground-line.

However, it is to the canal side it is most dramatic. The other side of the six feet of water is a small, galvanised lip, maybe a foot above the water level, and then, nothing. The narrow-boat sides will be way higher than this, so to go across by canal and look upstream it will be as if the canal is floating above the valley floor. But the thought of crossing on a boat with a child or dog on board, I think I would lock them securely inside.

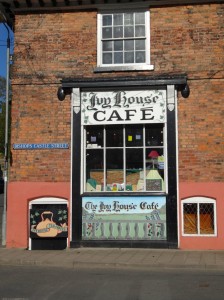

On the far side is a basin with tea shops and pub. A lovely place to spend an hour relaxing, but I feel it must already be well on its way to seven o’clock and I need to get to the far side of Trevor where the path sets off along the hillside, find the pub there, order a half and a taxi (in order) to get to Llangollen and eat. So I follow the pathway under the canal (a different view of the aqueduct), and along the Llangollen branch of the canal for a short bit further before crossing a lovely worn stone canal bridge and past some friendly horses and the road leading out of Trevor.

For the first time this day I dare to look at the time on my phone in the rucksack (I am so paranoid about battery use, I still just keep them there and do not touch them unless I have to). With trepidation I press the button to wake up the phone, my time estimation is always optimistic, I am always saying (Fiona will attest), "it can’t be that time already". But, when I look, oh joy of joy again, the time is quarter to five.

I had set 5pm at Trevor as the deadline when I would opt for a taxi from there to Llangollen, but my slow progress over the broken pathways meant I had long given up that thought. I was a full two hours earlier than I had imagined. I think a combination of my own fatigue and the cloud coldened sky had fooled my normal temporal optimism.

Elation at discovering the true time and a bite of Wispa bar, and my fatigue fell off me, even the pain in my feet felt less bad as I set off up the hill out of Trevor. On the whole the path makes a gradual ascent diagonally uphill along the valley side, but I missed one sign and followed the road almost straight up the hillside for a short while before realising my mistake and backtracking. I notice that many of the path signs are missing, the posts are there, but empty circular depressions where the signs should be. This could just be age, but I wonder whether a local landowner has deliberately removed signs to discourage walkers. However, I had no such excuse, the turn-off was well marked, just down a private road, so I probably just passed that by without looking. Even an unnecessary climb did not quell my sprits, and they lifted yet further as I first glimpsed Dinas Bran ahead.

Bran is a semi-mythical figure, demi-god, king of Wales who defeated the Irish over the honour of his sister, Bronwen, perished in the attempt, but whose head spent a pleasant year still conversing with his retainers, before it was buried at Tower Hill in London. It is said that while Bran‘s head was there Britain would never be invaded, but that Arthur dug it up as he thought the brave men of Britain could defend themselves without the aid of legends. Maybe he would have been better to have left it in place.

The hill in which it is placed rises sheer above the valley, a cone topped with the rings of an Iron Age hillfort and the broken remains of a Norman castle. An unparalleled command of the valley below and one of the major routes to West Wales.

The forest and then hillside path eventually joins a small mountain road cutting below the limestone escarpment, and the evening sky clears into occasional sheep-wool clouds and glorious low sunshine, now clear, now broken, that slices the valley with alternate gold-glow grass and sharp cut shadows.

And I decide.

I decide that I cannot pass the foot of Dinas Bran.

So, where a small lane drops its way towards Llangollen off the contour-hugging mountain road, I follow it for just a hundred yards before turning towards Dinas Bran. The climb is steep and sharp, but well managed, snaking back and forth up the hillside, a pleasant and exhilarating evening walk if you are staying in the town. But at the top, it is hard to find words, especially if you are out of breath.

And it is breathtaking, even when you have recovered your breath. The Iron Age ramparts cut through solid rock and the tattered Norman remains frame the distant valley and mountain views to all sides. It would be stunning at any time, but the combination of the light on the hillsides, sense of achievement at the day’s travel, and fact that in every direction I looked out and down meant I literally felt on top of the world … and there was even mobile phone signal to ring home at last.

And it is breathtaking, even when you have recovered your breath. The Iron Age ramparts cut through solid rock and the tattered Norman remains frame the distant valley and mountain views to all sides. It would be stunning at any time, but the combination of the light on the hillsides, sense of achievement at the day’s travel, and fact that in every direction I looked out and down meant I literally felt on top of the world … and there was even mobile phone signal to ring home at last.

As I’d climbed I’d noticed strips of plastic ribbon between posts that I’d thought were to encourage walkers to use the made-up paths rather than erode the grassy slopes. However, coming down I began to meet marshals for the annual fell race that takes the runners up Dinas Bran, not once but twice, before descending again to Llangollen. I met three, one after another, and each, from the oldest to the youngest, a teacher in the school, said that when they had been walking up the hill earlier in the day to lay out the route, walking itself had been exhausting enough let alone running. I told one about Arry and her multi-marathon run, and he gave me what change he had in his pockets for the charities I’m collecting for.

And then finally into Llangollen, the road down coming into the town round the back of the Bridge End Hotel where I am staying for the night, where I am shown to my room that overlooks both the river bridge to one side and the mini-steeples of the taxidermist next door on the other. I have visions of inebriated drinkers from the Bridge End, accidentally taking the wrong door and ending up, their skins already half tanned with alcohol, stuffed heads in the taxidermist window.

The Bridge End kitchen is closed on Wednesdays, so the day ends with the image of a tattered traveller, like a Chaucerian pilgrim, his worn boots swapped for sandals, straggling hair falling from his shoulders, making his way slowly and hesitantly from foot to foot, across the bridge in search of long-awaited food.