The common notion is that women talk, but in my experience of B&B proprietors, it is the men who are the talkers. Maybe ‘talker’ is precisely the right word, as, true to stereotypes, the men seem to be collectors of facts and information and are willing to share it with minimal encouragement.

The common notion is that women talk, but in my experience of B&B proprietors, it is the men who are the talkers. Maybe ‘talker’ is precisely the right word, as, true to stereotypes, the men seem to be collectors of facts and information and are willing to share it with minimal encouragement.

Certainly I learnt much from Keith over a relaxed breakfast.

The best place to catch the Royals is evidently the Menai Bridge Waitrose where Kate pushes her trolley along the aisles with a lack of airs that has made the couple popular on the island.

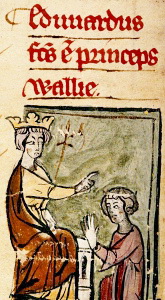

I recall the investiture of Prince Charles as ‘Prince of Wales‘ in 1969 when I was in junior school. I am by nature a romantic and took it at face value as part of Welsh national pride. However, I did not know the history of the title. In 1301 Edward I, after a series of bloody campaigns to subdue Wales when he had asserted his and England‘s control1. In Caernarfon Castle he stood on a high balcony and addressed the people.

"Do you want a Prince of Wales?", he asked.

"Yes", the crowd shouted, thinking they were to be offered back at least some semblance of a vassal state.

"I give you your Prince", he cried, their momentary hope destroyed as he held up his infant son.

Thenceforth each successor to the throne has been given the title ‘Prince of Wales‘, historically a sign of Welsh humiliation, not pride.

I knew nothing of this as a child, but as I treasured my Investiture Mug, given to all school children, and watched the pomp on black and white television, the Free Wales Army, in typical amateurish defiance, attempted to disrupt the ceremony with makeshift bombs, one of which injured a child slightly when the police ignored the telephone warning of where to find the bomb; the only blood, save scuffed knuckles, in the last armed Welsh uprising.

Where paramilitaries failed, successive years of non-violent resistance and slow political pressure have afforded a growing independence. Given William and Kate‘s obvious popularity and natural ease, I wonder if, by the time William, in turn, takes on the title ‘Prince of Wales‘, it may be as the constitutional head of state of an independent nation.

I have been fascinated by the micro-communities of the caravan sites ever since the wonderful welcome I received at Monmouth Caravan Site. I learnt that far from being quiet out of season, the B&B stayed busy throughout the year. One source of customers was Wylfa, the nuclear power station, where temporary construction or maintenance workers would seek accommodation even this far afield. However, the other was a sort of overflow from the static caravan sites that surrounded Benllech.

The caravans are mostly owned by retirees who spend nearly their whole year here. During the summer, when family visit, they are often put up in the B&Bs either because there is no room in the caravan, or because they prefer respite from small children overnight. During the winter the caravan sites close for two months, a statutory requirement to show they are ‘temporary’ not permanent housing. But for many, this is their home, and even if they have a house somewhere else they would prefer to stay close, maybe visiting their caravan during the day even if the electricity and services are cut off. So they stay, flotsam of the winter gales, in the shelter of Benllech B&Bs.

The Coast Path out of Benllech runs along the wooded cliffside. The path is narrow in places, and sometimes quite steep down to the sea, but usually wider and well levelled where the cliff is steep. I find myself catching up with a group strung out along the path ahead, and decide that I will need to simply relax and take my time behind them, but then come to a slight opening with a bench where they stop for rest.

They explain that they are an Anglo-French walking group who converse electronically during the year and then get together once a year for a walking and language week. Alternate days they speak English or French. I’m not sure if I was lucky to catch them on an English day, or whether they took pity on me and spoke English.

"This is nothing", one of them said, looking at the narrow cliffside path; "last year in France the path was this wide", her hands just inches apart, "and a hundred feet sheer down to the sea.". They are clearly experienced walkers as well as linguists.

Pleasure yachts and an RNLI lifeboat bob in sun-drenched waters. The village of Moelfra sits on a bay with dinghies and tenders pulled up on the shingle beside the quay. It is nearly noon, and I have a cup of tea at a quayside kiosk and put on suncream before the day gets even hotter.

The lifeboat is at the heart of the village, there is a statue of a lifeboatman and a monument commemorating the loss of the Royal Charter in 1859.

The Royal Charter was the fastest ship in the Australia run in the midst of the gold rush. She was on her way back filled with returning miners, their pockets full of gold nuggets, having made their fortune and looking forward to life of ease in their homeland.

Their journey was almost at an end, and within sight of the shore a Force 12 hurricane struck. Along with 133 other ships along the western coasts of Britain, the Royal Charter foundered, and of 500 on board only 40 made it to land, the rest, with their gold, sunk in the depths of the Irish Sea. As part of the rescue 28 Moelfra men made a human chain out to sea to help the survivors to land.

Soon after, the first Moelfra lifeboat was launched and has saved countless lives, including the full complement of the Hindlea, which foundered almost a hundred years to the day after the Royal Charter, in winds of over 100 miles an hour. With the propellor of the storm-tossed Hindlea spinning above the heads of the lifeboat crew, they managed to come alongside ten times, rescuing the entire crew of the Hindlea, and earning themselves medals for bravery. And all of them, and indeed all {{RNLI} crews, volunteers, their only reward to know they keep safe the seas and the thanks of those they help.

There is a RNLI museum and a short way along Moelfra Lifeboat Station.

One of the crew is standing outside and starts to tell me some of the stories of the boats and crews who served the coast for so many years. He invites me in and offers me a cup of tea … well can I say "no"?

One of the crew is standing outside and starts to tell me some of the stories of the boats and crews who served the coast for so many years. He invites me in and offers me a cup of tea … well can I say "no"?

The lifeboat station is due to be rebuilt with space for a viewing gallery, so that visitors can see the boat without interfering with its work, even when it is being launched. The building of the new lifeboat station is however being prompted by the new lifeboat which had just come into commission and is too large to be brought fully inside.

As I leave he suggests I stop for a meal at the Pilot Boat in Dulas and tell them that he has recommended them; he reckons they may give him the odd free pint for his PR efforts.

The way beyond Moelfra is more open and the cliffs low to the water. I pass the stone monument where the Royal Charter sank. It looks so peaceful, the odd walker, sun glinting on the sea, and a diving boat in the water, maybe seeking dead men’s gold.

I come to the next bay and see a group of older people on the beach ahead. At first I think that the Anglo-French group overtook me whilst I was seeing the museum and lifeboat station in Moelfra, but then discover they are a group of amateur geologists investigating the rocks.

The sun beats hotter and swirls of smoke-like mist rise from the damp sands as I cut directly across to the far side, wading the shallow water along the way. I mistakenly think this is Traeth Dulas, a deep inlet and am pleased as I get to the other side as I think I have cut off a mile of walking up and down the estuary … but then realise this was just Traeth Lligwy, a shallower bay.

Traeth Dulas is a minor estuary and the path cuts along one side, on the green hills above the steep wooded cliff, then down a small lane until ahead is an old, brightly painted double decker bus. It is the Pilot Boat and its children’s ‘Fun Bus’.

Following the lifeboatman’s advice I have a meal there and a pint, a very belated 4 o’clock lunch, and then set off again across a small bridge and then onto the old road that crosses the water at a ford.

Rather than skirting the full muddy length of the estuary edge, the path cuts inland and up, past the tiny hamlet named ‘Dulas‘ on the map (the very slightly larger scattering near the Pilot Boat is strictly ‘City Dulas‘) and the church of St Gwenllwyfo and then back down past farm and fields of sheep to the grassy cliff tops again.

I can’t recall if I first heard or saw the lamb struggling by the cliff edge. A fence protected the edge, but a lamb had its head stuck firmly through the four-inch square mesh of the pig netting. As I approached it became more agitated and I was worried I would do more harm than good, but as I touched it, it instantly stilled, and slowly, I shifted its head, the firm wool coat soft under my fingers, rotating it until it slipped free and it skipped carelessly back up the field to find its mother.

To sea there is a low island, or simply rocky shelf, on which is a tower looking not unlike the tops of the tall monastery bell towers you see in Ireland. On the map I see it is called Ynys Dulas and it simply says ‘tower’. At the time, I wonder whether it is the home of a hermit, like the island below the Severn Bridge, or a warning for ships, a lightless lighthouse, but having now checked online, I find that rather (or as well as) warning mariners off the rocks, it was built in 1821 as a shelter for those already shipwrecked and finding their way to this forlorn rock.

It is after five o’clock and I still have several miles to go. The scenery is beautiful but I am glad when Port Amlwch gradually comes into view and I walk past the museum of the copper industry and the deep docks into the town. The wait for the bus is not long and soon I am on the long journey back to the campervan still at Llanfairfechan.

- He was no more kind north of the border where he was known as the ‘Hammer of the Scots‘[back]