I wrote the first words of this day’s post with a large plate of gammon, egg and chips in front of me at the Sloop Inn in Llandogo. This is not insignificant as food … or the lack of it … has dominated my mood during the day.

The original plan was simple. I start the far side of the Severn Bridge, walk the few miles to Chepstow, then pop back and forth to the start of Offa’s Dyke on the banks of the Severn, then have a late breakfast at Chepstow, before making my way to Llandogo.

That was the plan …

Things started well, I left Severn Bridge services at 9am. The bridge over the motorway runs along the roof of the toll booths, which seems an odd irony walking over the top of those queues of cars waiting to pay their fivers for the privilege of coming into Wales. On both the old and new Severn crossings the toll booths are only one way. You travel from Wales to England for free, but have to pay to enter Wales. I have always claimed that this is because otherwise everyone would want to come to Wales and some sort of control was essential.

Walking on the approach to the bridge I passed a group of walkers going in the opposite direction, and even two runners. A group of cyclists passed me by, and one greeted me by name; it took a few moments to remember that this was because my name was on the back of my rucksack: “Alan Walks Wales“. There were many cyclists passing, I guess a regular route for Saturday morning.

In fact when I got on the bridge, I realised it was almost eerily quiet, the entire bridge was closed to traffic for maintenance. I had noticed the evening before that beyond the rumble of traffic, the bridge was surprisingly serene, and, now, with no traffic, so calm.

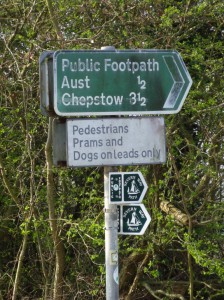

The run into Chepstow was uneventful, but a bit longer on the Wales Coast Path than the 3.5 mile route signposted at Severn services. The coast path tries to hug the banks of the Wye and alternates between housing estate, woodland paths and edges of industrial estate. One spectacular stretch lies along an alley with warehouses to the left and chain link fence to the right, and then a yawning chasm, possibly 150 feet deep, beyond which sheer cliffs rise the opposite side of the quarry.

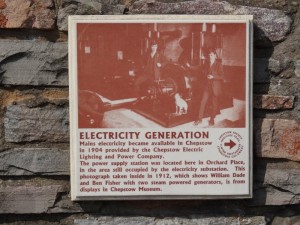

Wending slowly into the town past the post office and funeral parlour, supermarket and Wetherspoons, eventually the path cuts back down an old church alleyway towards the river again. The church had a notice board, and on the notice board a small card with QR codes on it … and I’m not even in Monmouth yet. The card is by historypoints.org; I need to look them up. Although this was the only digital signage there were ceramic information plaques on walls across the town, both beautiful and telling in small snatches the history of the town. In particular I found that Chepstow and Wye mouth were not only the site of old border disputes (William the Conquerer‘s castle to subdue the Welsh, (and not far off Caerleon where the Romans did the same for the Silures), but also a major centre for shipbuilding during the First World War, with workers being drafted in from as far away as the Clyde.

In fact, strictly, the church’s QR code was not the only digital signage, as in one of the streets approaching the town there was a car with musicwithmummysuzie.co.uk painted in large pink letters on its side. This made me think of the music groups my daughters took part in when they were little and how much music was a part of their lives then, and part of their careers now.

Beyond the church with the QR code it is not far to the riverside, the cliffs rising steeply opposite, a union flag painted next to the mouth of a deep river cave, and then … like a miniature stone circle, a ring of inscribed stones surrounding a circular plaque on the ground … the end of the Wales Coast Path.

The Coast Path begins/ends by the old bridge across the Wye, and the Offa’s Dyke Path passes close to the opposite bank. I had misremembered the distance to the end of Offa’s Dyke from here to be 0.8 miles, it is in fact 1.81 … and it seemed a long 1.8 for that, not helped by a significant number of signs having been vandalised. It would have been better to save a few miles on my feet and get a taxi from Chepstow to the start of the trail, as it was a little disheartening walking through the paved streets of Sedbury knowing that I was soon to retrace my steps, indeed so absorbed was I in a little bout of self-pity, I almost missed the moment when I was first walking along the top of Offa’s Dyke.

A short while further, a small sign announces "congratulations you’ve almost finished". As I was only just starting, and feeling pretty tired already, it was both reassuring that I was near the start, but also very slightly like a poor joke. However, there was a feeling of exhilaration actually standing on the spot of the Sedbury cliffs where the plaque announces the official start of Offa’s Dyke.

Looking south, the two Severn Bridges dominate the landscape, as they had during the previous day, linking the two. So to the south the 20th Century, but to the north, as soon as the path dips back down the far side of the cliff, one enters old times, walking Offa’s Dyke, where 1200 years ago it was raised by human-powered civil engineering on an epic scale and Saxon feet first trod its ramparts.

A man and his son came walking along the cliff path, discussing where the Offa’s Dyke Path ended; the man said it went to the north of Wales, but didn’t know quite where. Routes and destinations have been so much part of my consciousness that it is easy to forget that for the local person, it is simply a landmark. The man told me of the joys of living so close to a lovely part of the world, but feared that a long planned bypass for Chepstow would cut through this small strip of farmland between Sedbury and the cliffs en route to the M4. I assume they would have a flyover across Offa’s Dyke.

[the following written April 2014]

The man offered to take a photograph, so I have a snap of me and my rucksack waiting to set off from the ‘start’ of 186 (or 168 depending on the sign) miles to Prestatyn on the North Wales coast.

They set back off down the path along the water’s edge and I set off north, back along the early ramparts of Offa’s Dyke, back along the streets of Sedbury and past an ancient gnarled tree in the heart of a modern estate, past a cul-de-sac marked Offas Close, back along the small lane with high walls either side, like a scene from Hardy, until I stood on the steps looking down towards Chepstow.

When I had walked through Chepstow I had wondered that I had not seen the castle. When you come by train the castle appears to dominate the town, and yet, while I came through the town walls, I never saw the castle. Now I could see it clearly. When I had crossed the old bridge it would have been behind me, high on the cliffs looking down on the river, guarding the traffic. But I never looked back. I wondered, not for the last time, how different things would be walking in the opposite direction.

When I had walked through Chepstow I had wondered that I had not seen the castle. When you come by train the castle appears to dominate the town, and yet, while I came through the town walls, I never saw the castle. Now I could see it clearly. When I had crossed the old bridge it would have been behind me, high on the cliffs looking down on the river, guarding the traffic. But I never looked back. I wondered, not for the last time, how different things would be walking in the opposite direction.

Now it was already one o’clock and I had not had any breakfast bar a chocolate bar. I should have stopped for breakfast on my way through as it had already been half past eleven, but I had thought "I’ll just do the short walk to Sedbury Cliff and back". I had thought that Offa’s Dyke Path would take me back through Chepstow, but in fact I had been looking at a county boundary line. In fact Offa’s Dyke turned away on up the steps. When I realised this I should have walked the short distance back into Chepstow. But I was worried about time as I still had a long way to go up the valley to Llandogo and thought that one of the villages I would be passing through would be bound to have a shop or pub.

So I went on.

The way led up the valley side on the east of the Wye, until it crossed grassland towards a large Victorian semi-mansion, its mock-tudor woodwork painted green and white like a play-park shelter.

As the path cut across the mown lawns, straight ahead there was an Offa’s Dyke sign and an inviting lane running below a wooden bridge that connected the house to the river without crossing the peasants’ path between. I followed it down, past an old wall that suggested there had been major houses here for some time, unless it were merely a Victorian folly, and dark viewing holes through which the flash of my camera showed long passage ways, maybe simply storage, but in my minds eye the stuff of Famous Five.

The peasants’ path followed the river bank along, gradually dropping as huge red cliffs rose above. It became less and less lane-like, and more and more narrow and rough, until a point where I clambered down to the waterside. There I met a man, out for a stroll through the woodland, who told me that I had gone far wrong; Offa’s Dyke Path actually ran along the top of the cliff and there was no easy way to rejoin it except to turn back the way I had come.

Although frustrated to have wasted time when I was already late, I also relished the lovely woodland I would have missed if I had not gone astray, I was reminded of the time in Ireland when I had missed my way in the car and ended up at the most glorious beach at the end of a 13-mile dead-end.

It turned out that the Offa’s Dyke sign by the house I had seen had in fact had an arrow pointing right, directing you in front of the house and down its drive to the road; I had been so enamoured by the wooden-bridge-framed path I had assumed it was the right way.

The path follows the road for a bit and then round the back of houses and touches a few villages and groups of houses, but there was no sign of a pub or shop or tea shop. I had yet to learn that the distances between refreshment and food are writ for cars not feet.

To be fair the Harvey’s map did not show any symbols for shops in these villages. I had simply assumed it was only marking major ones, in fact it was very accurate and an excellent guide – if it showed no refreshment there was none.

During this time it also followed the red cliffs high above the path I had been on earlier, just as the man had said. The red sandstone of the riverside cliffs had been cut away in vast quarries, and climbers with brightly coloured ropes clung to the sheer sides. This is the place called Wintour’s Leap where, during the Civil War the fleeing Royalist Sir John Wintour had escaped the pursuing Roundheads by taking his horse down the near sheer sides of the valley and across the river.

I was now in the open country following sometimes along the top of the dyke, sometimes along its side. Although it was still April the day was hot and the sun beat down from behind. That evening I would discover that my arms, the top of my head, and the tip of my left ear were scorched and sore. I drank water and ate another chocolate bar, and saw from the map that the first place marked with food was the pub at Brockweir, many miles ahead.

Offa’s Dyke Path runs along the valley top, sometimes in the midst of trees, sometimes with vistas along the length of the Wye. After some time, when the path again broke clear of the trees, Tintern Abbey appeared, soft focused by river haze, spread on the calm grass bank as the river curves around.

Offa’s Dyke Path runs along the valley top, sometimes in the midst of trees, sometimes with vistas along the length of the Wye. After some time, when the path again broke clear of the trees, Tintern Abbey appeared, soft focused by river haze, spread on the calm grass bank as the river curves around.

By this time I was getting increasingly hungry and, more critically, my water was also low. Although it is possible to drop down into Tintern from the path, it is a long diversion, and a long way back uphill. So I went on.

As well as the hunger and thirst my shoulders had begin to ache badly, especially a point on my right shoulder blade. It is my Apple-injury, which I often notice whilst driving, the result of using the oh so pretty, but ergonomically hideous track pad on my Mac.

Soon after Tintern I met a couple walking the opposite way down the path, one of only three walkers I met during the whole day once I’d left Chepstow behind and before I came off the path at the end of the day at Bigsweir. We chatted for a while, and when I mentioned my water was getting low, they gave me some of their own. I learnt later to have more larger water bottles, as they had, but I was still young to the path.

So refreshed, but still hungry, I set off with fresh purpose and grateful for the kindness of strangers.

The end point of this day’s walking was to be Llandogo, about a mile off the track and just over half way between Chepstow and Monmouth. It was another nostalgic stop, as it had been where my Mum and Dad had taken their honeymoon, and where we often went for day trips when I was a small child.

I recall one day especially, when we had stopped at a field and were walking amongst the grass where Jacqui and I picked daisies. Jacqui, nearly two years older, was more efficient than I, and had a large bunch when she unexpectedly came to a spider’s web by a gate. In panic she dropped the flowers and they fell amongst the web, from which she would neither retrieve them herself or let them be picked.

They were simply flowers and there were many more, yet long after, well after the flowers would have withered and become dust, after the web had blown away and seasons come and gone, I still felt the sense of loss; and truth be told as I feel myself that young boy now, I still recall and feel in my heart, as I did then, that nameless presentiment of the ending of things, of the many small deaths that make our life.

They were simply flowers and there were many more, yet long after, well after the flowers would have withered and become dust, after the web had blown away and seasons come and gone, I still felt the sense of loss; and truth be told as I feel myself that young boy now, I still recall and feel in my heart, as I did then, that nameless presentiment of the ending of things, of the many small deaths that make our life.

Llandogo was not easy to get to by public transport, so we did not visit for many years after Dad died. Once, in my late teens Mum organised a bus trip to Tintern; a coach full of ladies, mainly in their sixties and seventies. Then some years later when I could drive (a Vauxhall Astra not a Ford Popular), we took a trip along the same ways that Dad would have driven, although with too many years between for the landscape to be familiar, albeit remembered in my heart.

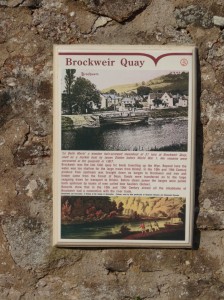

Llandogo is on the west bank of the Wye, but Offa’s Dyke Path passes on the east bank. There are two alternative routes for the path in its last few miles before Bigsweir, the closest point on the path to Llandogo. The first, shorter, route stays high and cuts off a bend of the river, while the other cuts down to the valley bottom at Brockweir and then follows the river bank. On the map there was a pub marked with food at Brockweir, so I chose the longer path and came at last to the Brockweir Inn – at last something solid to eat.

But alas, the Brockweir Inn does serve food, but not during the afternoons: lunches, and dinner after 6pm, but at 4pm in the afternoon, nothing, not a sandwich, not a pie; so my late, late breakfast consisted of a pint of beer and two packets of crisps. However, it was good to get the weight off my feet, and my rucksack off my back.

Behind the bar was a young man in his early twenties. I can’t recall if I mentioned my slight detour back along the banks of the Wye, but he told me a story of a trip that he and some friends had made a few years ago.

One afternoon they had decided to go for a visit to Chepstow, just six miles away down the river. They were young and knew the way, so set off without a second thought. They walked for some while, but eventually realised they had got lost. They tried to find their way, but the light dropped and they had no torches, so at last, in desperation, they rang 999. Happily they had phone signal. The police came out and sounded their claxon while the lads, like a submarine sonar, said "nearer", "further", "to the left", "to the right", until the police worked out where they were and sent a river boat to pick them up.

It was only afterwards when I thought about it some more that I realised just how desperate a group of fit 20-year-old men need to be to admit they are lost and call out the police.

I finished my pint and my crisps, and set off once agin, to go the few miles left following the flat grassy river bank to Chepstow. I could have crossed the ridge and instead followed on the opposite bank and roadside, which would have been a shorter way to go as I would need to double back along the west bank once I got to Bigsweir. However I wanted to stick to the ‘proper’ path, even if it were longer.

At the start of the path was a sign saying that there had been erosion of the banks and a diversion was in place. I almost considered going back up the hill to the high-level path, but the thought of the long pull up was too much so I set off along the river bank trusting to the diversion when it came. After about a mile, just as it had been told, a gate was closed off with plastic tape and another notice announced the path was closed and was diverted onto other public footpaths, but no directions as to where.

The only directions were either back or a public footpath going up into the riverside woods to the right. It was the only footpath going, so I took it. It must have been the intended way, but a lot rougher than any of the paths so far. Through the woods there were numerous tiny tracks that would have been pleasant for an afternoon stroll, but became harder and harder as my lack of food and the long day took their toll, and my tired feet became more and more clumsy. I wanted to walk as slowly as possible to avoid tripping, but also was worried that I would arrive in Llandogo too late to find food.

As I walked I pondered on the young man’s story and realised that if I fell now and even sprained an ankle it would likely be the next day before I was found. Amongst the trees I would be unlikely to have phone signal, the B&B would think I was a no show, and Fiona would assume I hadn’t rung because of lack of signal.

Before I had left I had seen a SPOT device advertised. It is a small GPS receiver that also can transmit to satellites. The device is equipped with an SOS button that sends a signal to the satellite with your location and then the SPOT service will alert the emergency services. It can also be set to periodically transmit so that your support team or family can know where you are. It is designed for those doing jungle adventures, off-piste skiing and the like and the SPOT service has a contact database for rescue services from Bolton to Burma.

I had toyed with the idea of getting one as it would be useful to have the live signal as the phone-based ViewRanger service I would using would be limited to areas with mobile phone coverage. The device was not too expensive for what it did, around £100, but there is also an annual contract for the service at another £100 or so, so not negligible all told. And it seemed total overkill! I wasn’t going to the upper reaches of the Amazon2, just Wales, and would be on Offa’s Dyke and the Wales Coast Path, surely with frequent passers-by.

However, on only my third day on track I realised that you can be just a few hundred yards from a road, but if you fall and break your ankle you could easily be hours or days before you are found. UK nights in April are not like the Arctic and the largest predator is likely to be the farm tabby cat, but hypothermia can soon set in. And here, in the Wye Valley on a sunny Saturday afternoon, the path was not awash with day walkers, but instead I had met at most three or four during the whole day.

So, later that evening, I asked Fiona to order me a SPOT device, which found me a short while later and I never regretted it.

However, I am still not in Llandogo. The wood walking seemed to last for ever, but was probably no more than 20 minutes. Where there was a choice of paths, I took the path to the left, which would run lowest down the valley side and closest to the river. Then eventually, I came out by a small lane, a house visible at the end. Along the lane were daffodils, not just growing from the bank, but in small vases to greet the visitor. Then, a short way from the house, in a small gap amongst the roadside hedge, a votive offering, a wreath of branches, almost as if they had fallen naturally, but clearly placed with care with a glass jar full of daffodils in the middle.

However, I am still not in Llandogo. The wood walking seemed to last for ever, but was probably no more than 20 minutes. Where there was a choice of paths, I took the path to the left, which would run lowest down the valley side and closest to the river. Then eventually, I came out by a small lane, a house visible at the end. Along the lane were daffodils, not just growing from the bank, but in small vases to greet the visitor. Then, a short way from the house, in a small gap amongst the roadside hedge, a votive offering, a wreath of branches, almost as if they had fallen naturally, but clearly placed with care with a glass jar full of daffodils in the middle.

Rebecca Solnit wrote A Field Guide to getting Lost, glorying in the joys of the uncharted, the magic you find when you are prepared (or forced) to lose yourself.

And then, oh joy, I came to an Offa’s Dyke sign, I had rejoined the way. It was then just a short way over some more fields, past a hollow tree and a fallen tree that looked like a dragon’s head, and then to the bridge at Bigsweir where a whole group of walkers, maybe 20 or more, some sort of club, were there, several times more than I had seen the whole day.

It was just a mile back down the road towards Llandogo. I ached, my feet were sore, and I started to count my steps to help the remaining time pass … and then realised I had no idea where I was going.

My laptop was in the rucksack, but my ‘where I am staying’ spreadsheet was in Google Docs, useless without an internet connection. Happily I did have mobile signal and as I walked the last few hundred yards into the village, Fiona looked up the details for me from Tiree and I came at last to the Lugano bed and breakfast.

Mrs Townsend made me welcome and put me in the ‘bridal suite’, a tiny sitting area opening out into a bedroom with a floor to ceiling French window looking out over the wooded hills.

The 50 yards down the hill to the Sloop Inn were excruciating, I had changed out of my walking shoes into sandals, so my toes were no longer crushed, but it seems that the moment or two of inaction had seized them completely. I recall ordering soup, wonderful and hearty, followed by the gammon with which I started writing, and a pint of something local, before making my way slightly less painfully back up the hill to bed.