a walk on the sands and a curious community, learning from locals, and the dog who was afraid of hats

8th July 2013

miles completed: 901

miles to go: 157

In the morning I left the Stables at Laugharne and drove to Carmarthen to check in at the Drovers Arms where I’m staying for the next few days, and to meet Alan Chamberlain. Alan was doing a sort of debrief about aspects of the walk, and as we chatted we had coffee, tea, bara brith, and lunch at the healthfood shop and café across the road from the Drovers.

Alan needed to get back to Aberystwyth and I was walking the nine miles from Llansteffan to Carmarthen, so at two o’clock (or so) we set off. Alan would drive me to Llansteffan before going home. The route back to Alan‘s car included a quick diversion into the Drovers to swap my laptop for water bottles, and a visit to the 99p shop to try to get a certain special brand of razor blade (not for me!), but before long we were out of Carmarthen and down to Llansteffan.

Alan needed to get back to Aberystwyth and I was walking the nine miles from Llansteffan to Carmarthen, so at two o’clock (or so) we set off. Alan would drive me to Llansteffan before going home. The route back to Alan‘s car included a quick diversion into the Drovers to swap my laptop for water bottles, and a visit to the 99p shop to try to get a certain special brand of razor blade (not for me!), but before long we were out of Carmarthen and down to Llansteffan.

Then we wandered along the quay to chat for another five minutes …

… at four o’clock, we suddenly noticed the time.

So, belatedly, Alan drove me back a few hundred yards to where I had got to the day before and was on his way. From Llansteffan the Coast Path heads inland over hills, and I was trying to work out whether to follow a road or something that looked like a private drive, as neither were marked and the arrow across the road could mean either of them.

"Are you looking for the Coast Path," an elderly lady asked.

The lady was standing outside her cottage at the crossroads.

Her name is Bron (short for Bronwen), her father was Welsh and her mother Irish, and the name was suggested by her grandmother, who, whilst Irish herself, had a love for myth and legend of both Wales and Ireland. In some ways as a Welsh princess who became an Irish queen, Bronwen is a good name for a child of both Welsh and Irish descent, but there again the story of Bronwen ended in war and bloodshed. Happily, Bron seemed to have escaped the calamities of her namesake.

"It is that way," she said, indicating the lane that looked like a drive.

"I see a lot of walkers confused," she said. "There used to be a sign, but someone has pulled it up, probably one of the farmers; some don’t like walkers."

She had seen both sides as the daughter of a farmer and as a rambler in later life.

There used to be a footpath and a Roman road at the bottom of the farm, and her father would sometimes block it with barbed wire, much to the embarrassment of her mother. However, when out with fellow ramblers, she had sometimes seen groups of young men with large dogs, leaving them off leash and not caring if they distressed animals.

She was not very complimentary about some of the routes for the Coast Path. "They cut corners," she said, and not meaning to shorten the route! "They simply found any existing path and used that."

Pointing to the path I should take, she said, "it’s not exactly coast." This was undeniable.

"It is very muddy and tortuous," she declared, and then expanded in more detail.

As she described the path’s meanderings she used the word ‘tortuous’ at least three more times. This did not sound promising. She said the main road to Carmarthen was busy at weekends, but at this time on a weekday would be quiet enough to walk. I am sorely tempted as (1) it is late, (2) it would be good to get back a little earlier after a fast road walk, and (3) the road is closer to the coast than the official path. However, I feel I may be using (3) as an excuse for (1) and (2), so am about to bite the bullet and take the tortuous route to Llangain, when Bron makes a third suggestion.

"You can go along the beach as far as the boathouse," she says, "and then join the road, but the path joins the road later anyway."

Doing more beach walking is one of my acceptable reasons for going ‘off path’; I am decided.

Doing more beach walking is one of my acceptable reasons for going ‘off path’; I am decided.

So, back down the hill Alan had driven me up, and down onto the beach.

As you go upstream from Llansteffan, there are a couple of rocky groynes to cross or go round, and the sand becomes silty and covered in hard packed ripples, fossilised until the next tide. Patches of what at first appear to be grey pavement-like rock appear, only if you kick slightly at their edges they break. They are not rock at all, but patches of silt and mud at the very highest point of the tide, stabilised by a thin layer of algae, and gradually compacting and thickening. It is not rock, but these are precisely the processes by which, over many, many years, rocks form.

I had slightly misunderstood Bron, and thought the boathouse was a small huddle of buildings on the map named ‘Ferrypoint‘; I assume this is the point from which the ferry would once have plied back and forth to Ferryside across the water. The shore side had had the occasional cottage or house, but there was a point with no immediate house, where a cinder track came close to the beach, where there was a footpath sign pointing the way, and along it could be glimpsed some sort of hut-like structure that I assumed was the ‘boathouse’.

Indeed, this was the path to Ferryside, but not to the boathouse. The building I saw was in fact a single storey, corrugated iron residence, number ’12’ of a loose cluster that ranged from tumbled down shacks, to neatly painted, and quite substantial beach houses, with modern large-section corrugated walls and roofs.

I felt I had been transported to the Appalachians, and expected that at any moment the sin-eater would rush past.

I wonder at this tiny hamlet and its history. Are they all holiday houses, or do some have permanent residents? It must have formed before modern planning regulations, and persisted, with updates and improvements to various properties. I look at the distance between this and the riverside. Do storm-pressed spring tides ever push up this high? Maybe it is just high enough to keep them clear, it is hard to imagine some of these properties surviving a flood.

Beyond Ferryside the path continues but as a grassy sandy track. From the map, it once led back to the road, but now that part is overgrown and instead leads onto the beach and along the foreshore. In the distance I see yachts and realise the ‘boathouse’ is in fact where my map says ‘jetty’, and is Towy Boat Club, not just a small private shed for a single boat.

After a while a bed of lush green reeds blocks the way and the path skirts this towards the water. When it finishes I keep going along the sand, until it changes to a sticky mud and I realise I am the wrong side of a marshy area. Maybe it is possible to go on and it stays simply sticky, but also it might turn to knee high river mud, so I backtrack and see that there is a well-trodden path heading shoreward round the edge of the reed bed. The shore is tree lined, and so, beneath trees and at the point where shore-side shingle and salt marsh meet I walk the rest of the way to the actual ‘boathouse’.

After a while a bed of lush green reeds blocks the way and the path skirts this towards the water. When it finishes I keep going along the sand, until it changes to a sticky mud and I realise I am the wrong side of a marshy area. Maybe it is possible to go on and it stays simply sticky, but also it might turn to knee high river mud, so I backtrack and see that there is a well-trodden path heading shoreward round the edge of the reed bed. The shore is tree lined, and so, beneath trees and at the point where shore-side shingle and salt marsh meet I walk the rest of the way to the actual ‘boathouse’.

There is a substantial jetty with a few boats next to it and more beached on the river mud. The boathouse itself is indeed a yacht club, which may well be open to non-residents as ‘croeso’, ‘welcome’ is written in various places. I am only a mile or so into my day’s walk, but it looks like a relaxing stopping point along the way.

Stepping out of the boatyard, there is about three-quarters of a mile walking along the road, before the official route also joins it, just beyond the hamlet of Pant yr Athro.

It is not a wide road and Bron had said that this could be nose to tail at busy times, so I can see why the official path keeps you off it as much as possible, but it has only the occasional car now.

When walking roads with no footpath, I have formed the habit of walking about a yard away from the road edge, rather than as close as possible, even if there is a grassy verge. Then as a car approaches I step closer in to the side. I hope this means cars end up giving me a wider berth, although there are some cars (and yes it tends to be young male drivers) that seem to delight in driving as close as they can to pedestrians.

When walking roads with no footpath, I have formed the habit of walking about a yard away from the road edge, rather than as close as possible, even if there is a grassy verge. Then as a car approaches I step closer in to the side. I hope this means cars end up giving me a wider berth, although there are some cars (and yes it tends to be young male drivers) that seem to delight in driving as close as they can to pedestrians.

Now the road is the official way they signpost you into one of those fenced-off sections of field beside the road. Sometimes these are wide, well-mown strips, but the first was anything but. The gap between hedgerow and barbed wire fence was shrunk by the overhanging hedge, and the ground below thick with bramble and stinging nettles. I was glad when, with smarting legs, I was once more able to rejoin the road and, not long after, branch up a quiet side lane.

Did I say quiet?

As I turned up the lane a black and white collie appeared a short way ahead barking loudly. As I drew closer, he was joined by a Tibby (Tibetan Spaniel) and another small white dog. When I got too close, he would retreat a few steps, but barking all the time and as I passed the drive of his house, he came behind, and then was barking inches from my calves. He was neither growling, nor snapping, so I did not feel alarmed, but, still, it is not totally comfortable having dog teeth so close to your flesh.

A lady emerged, calling to the dog and apologising in almost the same breath.

"It’s the hat," she said, "he’s afraid of hats."

I took off my hat and the transformation was instantaneous: he stopped barking, came up, sniffed at me, and then wanted to jump up, play and have his ears fondled.

At an earlier point of the Coast Path I had had a similar incident on a narrow cliff path, where a dog was with its owner and started to bark. Again it was the hat. On that occasions the owner said she thought that the fear was because hats hide your eyes and so the dog cannot see if you are friendly or a threat.

I talked with this lady about her Tibby, which was about twice as big in all dimensions as Tansy used to be. I said that they were like greased lightning running. "Not this one," she said, "he is lazy and stubborn". She found the collie, hat-phobia notwithstanding, far easier to handle than the little Tibby.

I talked with this lady about her Tibby, which was about twice as big in all dimensions as Tansy used to be. I said that they were like greased lightning running. "Not this one," she said, "he is lazy and stubborn". She found the collie, hat-phobia notwithstanding, far easier to handle than the little Tibby.

I continue along a few lanes past a small, disused church, which is half a mile from the village of Llangain, but was clearly once the local church.

A little further I see the water of the river Towy once more and enter a field. A notice says there are cows, calves and a bull in the field. At the top of the field a small 4×4 is stopped with a couple in the front and their two grandsons in the back leant half over the front seats to see ahead. As I pass the lady calls me and her husband then says it is best to wait as his daughter is rounding up the cows that have broken through the electric fence. As if to order, the sound of a revving quad bike rises from the bottom of the field, and she appears, periodically weaving back and forth behind the cows, sometimes having to swing back to corral a cow that has broken free. The boys keep up a running commentary on their mother’s progress as I wait and we chat.

The farm stretches all the way back to the church and down to the river, and thinking now, I assume ‘Church Farm‘, which is the only building by the lonely church.

The farmer explains that the lane I had come down, the path across this field, which is only visible because of the line of the electric fence, and the path through the woods that I would follow when I got to the end of this field, were all part of what once was the main road from Llansteffan to Carmarthen. This is why the church is so far out of the village; it was where the village road met the main road.

When his father took on this farm in the 1940s the field we are in was also woodland, but in those days, with food rationing still in place, farmers were encouraged to bring land into agricultural production, so the trees were grubbed up and the land turned to grassland.

He also tells me about the boats that used to come up the river, to unload at a wide basin in the river and transfer coal, flour and other goods to horse and cart to take them on into Carmarthen itself. Still a working port into the early years of the 20th century, in the 18th century it had a bigger tonnage than Cardiff.

Eventually the cows, calves and bull are rounded up to the far side of the electric fence, even though the calves instantly duck under again, and the lady-farmer roars up astride her quad bike.

She and her husband both have other jobs, as the farm, at 130 acres, is not enough to support them. She says that in her grandfather’s day it employed 15 men and their families as well as the farmer’s family, but now is not sufficient for one. I wonder at the change in things, food is still a major part of expenditure, so how is it that food production yields such a poor income. I recall the farms I visited when on the graduate induction programme at the NIAE many years ago; some were 25,000 acres (10,000 hectares), owned by insurance companies and employing maybe two or three permanent staff.

The road (not path!) through the woods is wide and although occasionally muddy in places, this seems so much different when you know it is a path with a purpose, a piece of history I am treading.

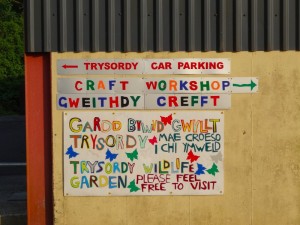

Eventually the old road joins the new road, but the path almost instantly branches off to the left through a very well-made woodland walk, then back on the road for a while, and those edge of field paths tracking the walk until it turns away towards a wonderful-looking place called ‘Trysorddy‘, ‘Treasure House‘. It is some sort of community centre, and Smartie-coloured bilingual signs point ‘Craft Workshop / Gweithdy Crefft‘, ‘Storfa Sgrap / Scrapstore‘.

Eventually the old road joins the new road, but the path almost instantly branches off to the left through a very well-made woodland walk, then back on the road for a while, and those edge of field paths tracking the walk until it turns away towards a wonderful-looking place called ‘Trysorddy‘, ‘Treasure House‘. It is some sort of community centre, and Smartie-coloured bilingual signs point ‘Craft Workshop / Gweithdy Crefft‘, ‘Storfa Sgrap / Scrapstore‘.

The path here is signed, but utterly obscurely, you have to turn round and then look almost the way you have been going. It then follows round the back of a sports field and some sort of sports centre or maybe store, before crossing a brook and joining a well-made path across the river meadows towards the heart of Carmarthen. On the far side of the river cows graze the salt marsh, but on this side a handful of horses have the expanse to themselves.

A gentleman in a grey jacket, looking as if he has come from a different age, is smoking looking out over the river, and I stop near him to photograph one of the horses.

A gentleman in a grey jacket, looking as if he has come from a different age, is smoking looking out over the river, and I stop near him to photograph one of the horses.

"Did you take that horse," the voice made me start. Did I do something wrong, is it his horse and he objects?

"It is thirty seven years old," he says, "they say a horse year is five or four human years, thats …"

"Very old," I interject.

He points out another: "that one is over thirty two."

He seems to know each horse individually, who owns them and who keeps an eye on them, as one of the owners now lives some way away.

Given the longevity I ask whether the ground here is especially good.

"Not in winter," he tells me, "you should see it after that."

I imagine the damp mists and sodden earth.

However, there is clearly something good here.

"The sheep and lambs from the salt marshes are all sold overseas," he says, "they think they are the best."

We get on to talking about foods that other nations enjoy, but the British do not appreciate, I mention the crabs from Tiree that all go to Spain.

He says, "Eels, the Chinese like them. There used to be eels in this river. There was an abattoir and a milk factory; the eels fed off them; when they closed the eels went too."

It’s strange, you usually think that cleaning up a river would increase biodiversity, and indeed may have done so; however, things may also be lost.

Coming along the riverside you notice the bridges, first a railway bridge, which can clearly rise like a drawbridge to let through tall river craft, although I would guess does not get raised often nowadays. Then the footbridge, a sinuous suspension, its curving walkway supported by two Christmas-tree-like pyramids, steel trunks and wires.

Coming along the riverside you notice the bridges, first a railway bridge, which can clearly rise like a drawbridge to let through tall river craft, although I would guess does not get raised often nowadays. Then the footbridge, a sinuous suspension, its curving walkway supported by two Christmas-tree-like pyramids, steel trunks and wires.

However, before the second bridge there is a small lattice-fronted shed, which I almost miss, thinking it is full of canoes, or small river boats, but then I realise it is in fact full of coracles.

Coracles are the traditional boat of rivers, a sort of hide (or now tarred canvas) covered round basket. They are in direct line from the hide-covered boats that would have been used at sea, including the one recreated for the Brendan Voyage crossing to America, and are also related to the sea-going curraghs of Ireland.

There were once hundreds of coracles fishing in these waters, but now only eight coracle fishing licences are issued. I wonder if these coracles belong to those licencees, or maybe it’s a sort of ‘coracle experience’ tourism.

Carmarthen was a Roman garrison and town, and then was occupied by the British when they left. Its Welsh name ‘Caerfyrddin‘ is ‘caer-myrddin‘ the fort of Merlin, and this Arthurian connection is celebrated in the Merlin’s Walk shopping centre, complete with statue of Merlin, resplendent with pointed hat (no pretence of druidic Merlin here, straight for Disney ‘Sword in the Stone‘), whom Alan Chamberlain thinks looks like me, and I think looks like him. Incidentally, the Welsh name for the shopping centre is ‘Maes Myrddin‘, which, I think, means more like Merlin’s Meadow.

I am staying at the Drovers Arms. It and several other hotels and hubs are at the west end of town, where the road widens into what must once have been the market area. ‘Retail development’ in the town has largely happened to the sides of the main streets, so that there is an eclectic mix of high street shops you would expect to find in the largest cities, with the more individual shops that have all but disappeared from most high streets. I spot an old barber’s pole and then realise that there is still a barber trading there, and on the Main Street a Victorian chemist’s frontage over a current day chemist.

I am staying at the Drovers Arms. It and several other hotels and hubs are at the west end of town, where the road widens into what must once have been the market area. ‘Retail development’ in the town has largely happened to the sides of the main streets, so that there is an eclectic mix of high street shops you would expect to find in the largest cities, with the more individual shops that have all but disappeared from most high streets. I spot an old barber’s pole and then realise that there is still a barber trading there, and on the Main Street a Victorian chemist’s frontage over a current day chemist.

The Drovers itself feels like the sort of place that the drovers and farmers visiting the market two hundred years ago would have visited. By this I do not mean olde worlde oak beams and four-poster beds, this is no romantic break hotel, but it is a basic ‘inn’. I notice that many of the people in the bar in the evenings also work there; the fact that the staff choose to spend more time here says everything about its atmosphere.