the second longest day, oil and power, whisky and waves, ribs in the rock

1st July 2013

miles completed: 841

miles to go: 217

This was my longest day since the wet odyssey from Holyhead to Rhosneigr in Anglesey, but more accident or happenstance, not planned that way.

This headland was one of my logistical problems, I wasn’t sure where to stay to do it and there are few stopping places en-route. It would be easier straight B&B-ing I think, but I’d not had sufficient connectivity and time to work this out. The bus routes are good around the headland, having passed both the watershed and also the bus-shed of Cleddau Bridge, but if I park at the end at Angle West Beach (15 miles) or Freshwater West (19 miles), the first bus does not get me to Pembroke until nearly 11 am. Even the short distance seems more than enough after the late start.

This headland was one of my logistical problems, I wasn’t sure where to stay to do it and there are few stopping places en-route. It would be easier straight B&B-ing I think, but I’d not had sufficient connectivity and time to work this out. The bus routes are good around the headland, having passed both the watershed and also the bus-shed of Cleddau Bridge, but if I park at the end at Angle West Beach (15 miles) or Freshwater West (19 miles), the first bus does not get me to Pembroke until nearly 11 am. Even the short distance seems more than enough after the late start.

So I decided to do it the other way round. Wild camping at Freshwater West made it easy to wake early and drive to Pembroke. Food is also a problem, there is nothing between Pembroke and Angle and then I wasn’t sure what there was beyond that, although the taxi driver the night before had helped fill in some of the gaps: evidently a very nice pub at Bosherton, and cafés at some other inlets.

My food problems have been compounded by a fault in the 3-way fridge. It is working fine off the mains electric, but I can’t get the gas flame to light, so cannot keep things cold when not in a ‘proper’ site.

So I drive to Pembroke, eat marmalade sandwiches and banana for breakfast and make doorstops of tinned ham. The latter is ‘Tudor’ ham, those oval tins with a sardine-can-key to open. We always had one of these as a ‘treat’ around Christmas time, but at no other time of the year. Thinking back, I think there were two sides to this. First, it was a dinner that required no cooking, always a plus for Mum as we had half-board lodgers through most of the year. Second, I’m sure it will have had awakened war-time memories for Mum and Dad, when tinned meat would have been a rare luxury.

So I open my tin and, as I turn the key, juices flow everywhere. Large amounts of kitchen roll blot it from the worktop and I thankfully avoid any dripping onto the carpet. Note to self, "next time open ham over sink". Slicing the ham across into quarter-inch slices gives a number of rectangular pieces that do not obviously fit well onto the curved ovoid slices of the sliced crusty bloomer that I’d bought in a five-minute shopping dash round Morrisons before 4pm Sunday closing the afternoon before. However, this is no problem, the trimmings and the large chunk left behind become part of my balanced breakfast (fruit, bread, meat, sounds healthy to me).

So, four doorstops of sandwiches in my rucksack, the van parked at the ‘commons’ car park in Pembroke (£1 the whole day), I set off, still well before 7am.

I pick up the path where I left off at the bridge beneath the castle and the first quarter of a mile follows the water around the castle, which takes me back to the road to Angle and the west, within sight of the van I’d left a short while before. The path then follows the road past a few housing estates. I meet my first and, if I recall, only person until Angle as I leave Pembroke. An old, and slightly confused seeming, lady, asked me where I was going. "Angle", I said, but while clearly local, she did not recognise Angle; I guess as a tourist you visit places that a local would never do. "I’ve seen two cyclists this morning", she told me. I felt slightly guilty as I moved on, as I felt she would like talk more, but also feared that the conversation would centre on the same few sentences.

I pick up the path where I left off at the bridge beneath the castle and the first quarter of a mile follows the water around the castle, which takes me back to the road to Angle and the west, within sight of the van I’d left a short while before. The path then follows the road past a few housing estates. I meet my first and, if I recall, only person until Angle as I leave Pembroke. An old, and slightly confused seeming, lady, asked me where I was going. "Angle", I said, but while clearly local, she did not recognise Angle; I guess as a tourist you visit places that a local would never do. "I’ve seen two cyclists this morning", she told me. I felt slightly guilty as I moved on, as I felt she would like talk more, but also feared that the conversation would centre on the same few sentences.

At Quoit’s Mill the road branches inland, but a smaller road leads straight onwards down a small hill to the water side, a road that can clearly (from road sign and remnants of dried mud) be occasionally flooded by high tides. The mill itself, if it still exists, is somewhere above, and the inlet seems to be sourced from what appears to be a giant tap, its outlet a foot and half across. It would take a very large big toe to get stuck in that tap. On the roadside below the tap is a large turd-like pile of white concrete, dumped and left to harden, and high above the tap, clearly the edge of some yard, where a few vehicles are visible, and an old, battered school bus overlooks the tree-hidden stream head. Soggy springs bubble beside the road, flowing across towards the tiny tidal marsh below. I wonder if this was the original road to Hundleton, the next village west out of Pembroke, and last before the coast, but then abandoned as the current road was built higher up and drier. This tiny valley certainly has a sense of abandonment.

At Quoit’s Mill the road branches inland, but a smaller road leads straight onwards down a small hill to the water side, a road that can clearly (from road sign and remnants of dried mud) be occasionally flooded by high tides. The mill itself, if it still exists, is somewhere above, and the inlet seems to be sourced from what appears to be a giant tap, its outlet a foot and half across. It would take a very large big toe to get stuck in that tap. On the roadside below the tap is a large turd-like pile of white concrete, dumped and left to harden, and high above the tap, clearly the edge of some yard, where a few vehicles are visible, and an old, battered school bus overlooks the tree-hidden stream head. Soggy springs bubble beside the road, flowing across towards the tiny tidal marsh below. I wonder if this was the original road to Hundleton, the next village west out of Pembroke, and last before the coast, but then abandoned as the current road was built higher up and drier. This tiny valley certainly has a sense of abandonment.

Eventually the road leads out and then you branch off down green lanes and field edges heading gradually towards Pembroke Power Station, its four towers standing tall and initially distant. It is my first milestone of the day, about five and a half miles from Quoits Mill.

Eventually the road leads out and then you branch off down green lanes and field edges heading gradually towards Pembroke Power Station, its four towers standing tall and initially distant. It is my first milestone of the day, about five and a half miles from Quoits Mill.

In fact, the closest approach to the power station is a few hundred yards to the south of what, I think, is simply a huge substation with humming pylons leading to those piles of glass plates that serve as high-power insulators. I can’t recall the exact voltages for long-distance wires, 135,000 volts comes to my head, certainly enough to fry you several times over.

Fiona‘s Grandpa used to work as an engineer of some sort in the power industry, but I think the more ‘white collar’ sort. He told me of the last-ditch test they would use before touching a power line. When doing work on mains electric, an electrician will sometimes flick a power line with the back of their hand. They only do this when they are certain the power is off, as they would get a shock from this, but by using the back of the hand they would not end up grabbing the live wire if their muscles went into spasm; it is better than grabbing it and then finding out. Similarly, in the power industry they had a long pole, with a fusible piece of metal at the end and an earth strap dangling to the ground. After doing every other check that the power had been shut off to the cable, they would tentatively touch the wire. If it was live the resulting bang would probably still knock them off their feet, but better than becoming instant KFC.

As I cross the road that leads into the heart of the power station, I see the Coast Path at the opposite side, but go down the road a little to take a photograph of the entrance signs, both a simple painted one, and also one of those orange moving LED lettering ones. A car pulls up, I guess someone just on his way to work.

He winds down his window. "Just checking you know which way to go," he says.

I assure him I do and saw the path a short way back.

I wasn’t sure if this was simply being helpful, or if he was checking I wasn’t an eco-activist about to single-handedly scale the towers and shut down the plant – honestly, sandals, beard and straggly long hair, do I look like an eco-activist?

With the power station behind me it is the tall towers and domes of the oil refinery that lie ahead. There are two sorts of towers, the tall thin towers with flames burning, which are, I believe, to vent excess gas should pressure build up anywhere, and the slightly less tall, but still very tall, distillation towers. The domes are partly large circular, dome-topped tanks and partly spheres on legs, reminding me of images from Thunderbirds … in fact I think one of the opening sequences was just such a plant exploding. I’m guessing the cylindrical tanks are for liquid, or maybe low-pressure gas, and the spheres are pressure vessels, but I don’t really know.

Before coming alongside the refinery, I pass the disused church at Pwllcrochan. I say disused, but the churchyard serves as the entrance to a community nature reserve for local children. There are no houses very close to the church and I guess much of its old parish has been buried under the refinery or power station, which sandwich it to west and east.

Some while later the path leads off the road again and goes for several miles beside chain link and razor-wire topped fences. Initially, this offers a panoramic view of the terminal, but then the land rises and the path runs through bullock fields on the slope running down to the wide estuary. There is a very faint, acrid, chemical taste in the air.

Unlike the caged-off paths and bridges near the jetties on the north side of the estuary, the path on this side takes you past a small slipway and under the jetty with pipes that leak a faint smell of gas and petrol. I’m not sure whether the difference reflects different levels of risk; maybe refining, having less volume, is regarded a lower grade risk. Or maybe it is financial, the storage on the far side will be a free zone, so Customs need to ensure that no fuel leaves it to the black market.

As well as the pipes taking fuel out to the tanker loading far out in the water, trucks rumble out and back along the jetty. On the waterside lie new pipes, destined for repairs somewhere in the plant or jetty, and a multicoloured metal fan spreads off one working pipe, the purpose of which is a complete mystery.

Past the jetty the path runs through waterside woodland, past an old lime kiln and ruined buildings, maybe a farm that lost its lands beneath the pipes, tanks and towers of the refinery. Beyond that an old concrete path, maybe wartime, eventually leads to a wide concrete road at the end of which is another Napoleonic battery, now sprouting grass and looking empty-windowed to the tankers passing, but in its time bristling cannons warding off the feared French invasion.

Past the jetty the path runs through waterside woodland, past an old lime kiln and ruined buildings, maybe a farm that lost its lands beneath the pipes, tanks and towers of the refinery. Beyond that an old concrete path, maybe wartime, eventually leads to a wide concrete road at the end of which is another Napoleonic battery, now sprouting grass and looking empty-windowed to the tankers passing, but in its time bristling cannons warding off the feared French invasion.

Ahead is Angle Bay and directly across the village of Angle can be seen. From this direction, the view is idyllic, yachts and fishing boats in the water, with cottages and church tower beyond. Further round the headland the lifeboat station stands, its long slipway dropping into the water. Although the path along the estuary, power station and refinery has been interesting, I am looking forward to the wild edge beyond Angle. It is a couple of miles round the bay, but initially on road and then waterside path, so I hope straightforward.

By the Napoleonic fort and where the path meets the bay-side road, there is a large compound. It appears to be a generic storage area, but in the middle, in a square formation, fifteen-by-fifteen, like a Roman army gathered for battle, over 200 portaloos gather ready to be sent into action wherever required.

As I turn to walk along the bay, I at first think there is a second refinery, a huge domed tank is closest and behind that more towers, but then I realise it is just the same refinery seen from the opposite end, over an hour’s walking end to end.

Beside the path are some old wartime buildings and what looks like a back entrance to the refinery, a gate that says:

This gate to be kept clear at all times

Emergency Access

It is wide open and looks as if it hasn’t been moved for years.

Beyond this last outpost of the refinery, on the far hillside, overlooking a lonely church in the middle of deserted countryside, is a relatively modern, low building, maybe administrative offices for the refinery. The church must be the remnant of Rhoscrowther, a medieval village abandoned and demolished when the refinery was built.

Beyond that the road heads inland towards a curious area, with what look like enormous artificial grassy banks. At the time I wondered whether this was the old Second World War arms dump, but checking on the internet that appears to be RNAD Milford at Newton Noyes, north of the estuary. In fact this area seems to be the site of an old BP oil storage site, and on Google maps you can see the circular marks on the ground. The storage area served the vast refinery 60 miles away at Llandarcy near Neath.

The path does not go on through the abandoned BP site, but continues along a footpath beside the water, bolstered by small-scale shore defences that look rather like sandbags that have been filled with concrete. After a while the path is across water-side fields, and then along a small woodland estate path, before joining a road for the last quarter mile into Angle.

The path does not go on through the abandoned BP site, but continues along a footpath beside the water, bolstered by small-scale shore defences that look rather like sandbags that have been filled with concrete. After a while the path is across water-side fields, and then along a small woodland estate path, before joining a road for the last quarter mile into Angle.

Angle is strung out along a road that leads for about a mile from Angle Bay, which faces north onto the estuary, to West Angle Bay on the far side of the headland, which faces out towards the Irish Sea. The church is at the east end near Angle Bay; inside is a children’s display about Africa and in the churchyard a tiny Seaman’s Chapel. I was wondering whether the seamen weren’t allowed in the church and why, but in fact it is not about where they worshipped, but where they were buried. Under the chapel is a vault where the bodies of unknown drowned seamen were buried when they washed up on the shores.

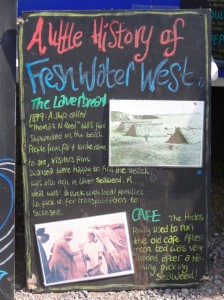

I’d eaten breakfast at 6am, and it was very hot, so I was considering taking a break at the pub in Angle and maybe having something to eat inside to supplement my Tudor ham door-stops. However, even after visiting the church and looking at the ‘Makers of Wales’ display boards opposite (from which I learnt that seaweed is still gathered here for laverbread), it was still well before noon, and so I decided to walk round to West Angle and then come back into Angle from the far side.

The path heads off along the waterside, with the refinery across the bay, past a farmhouse with a small square tower that looks very much like the Pele Towers you see in the Borders of Cumbria. I assume that this too was defensive, but maybe from a slightly earlier period. There is also a beautiful bench where the natural shape of the tree trunk is preserved in the seat back, and then further on a sign that reads, ‘Caution, free range children playing.’

Less than half a mile along the path is The Old Point House and it is just noon. I decide that while I’ll still wait for some lunch, a half of Felinfoel Double Dragon would do no harm. However, once inside I discover they have some special ciders, so have a half of one of those instead.

It is a lovely old inn, tiny and cool inside, but with plenty of benches for those who wish to take in the sun. According to the Guardian‘s ‘Top 10 Pembrokeshire pubs‘, The Old Point House dates back to 1500. The girl serving at the bar was clearly new and the landlord was explaining to her about the different beers and ciders, their strengths and flavours. On the wall were lots of artefacts and cuttings particularly relating to the local lifeboat and past crews; the lifeboat is based just a short way further round the headland. However, the most interesting thing was about the Welsh ‘Whisky Galore’.

On a stormy night in 1894 a schooner, the Loch Shiel, ran aground near the fort on Thorn Island. The Angle lifeboat saved all the crew, but the cargo, barrels of gunpowder and whisky, was lost. Before the revenue arrived to secure the cargo the locals had already made good attempts to salvage the barrels of whisky that were washing ashore. Of seven thousand barrels only two thousand were recovered, although many of the remainder sank or were washed away. It is probably fortunate that not all five thousand ended up in the hands of the Angle villagers. Although all the crew and passengers were saved, there were three fatalities. Two were local men who were lost at sea trying to recover floating barrels; history does not tell how much they had drunk by this point. The third man who died literally drank himself to death.

The lifeboat station is no longer the same one that saved the crew of the Loch Shiel; instead a recent box-profile steel station stands on the north tip of the Angle headland. While the cargo is now petroleum spirit rather than whisky, the channel is no less busy with both large tankers and many small pleasure craft.

The path leads through woodland and field sides along the north side of the headland. It is midday and the flies gather in each patch of shade in the still heat. Off the north west tip is Thorn Island itself. There is no trace of the whisky-laden wreck, but divers still recover bottles from the sea floor, and say that it is drinkable … but do they declare it to the Inland Revenue?

The fort is solid, almost filling the top of the island. With the first one on the headland at Dale it would have formed a pincer grip of cannon fire for any ship to pass between. Any that did slip through would find Martello Towers in the channel ahead.

West Angle is a sandy bay facing slightly north of west across towards Dale. Cars stand in line above the sea wall while children play in the waves. I am considering walking the half-mile back up the road to the Angle pub when I see a dilapidated beach café. Unfortunately it is not only dilapidated, but also closed. However there is a small burger and ice cream van. It is so tiny that the man inside cannot move, simply turn on the spot. In front of him is a small counter to serve and hold sauces, to his right a little freezer with ice-cream and supplies, and behind him a single gas burner. I order a burger, which he cooks in a frying pan, the burger filling the small frying pan, and the small frying pan covering the tiny stove. The tea he makes from hot water in a flask, which I assume he fills during quiet moments between customers.

I am always fascinated by the artfulness of those working in these vans with limited space and everything exposed to sight, but this is the smallest I have seen. I ask him what happens if he needs to cook more than one burger and he explains how he part-cooks sausages and burgers when it is busy so that he can serve them quickly. It seems such a small beach, but he says he is making a living. The café has been closed for a couple of years and he filled the void, but it is due to open again next season. There is no hint of chagrin or undue concern, he seems to have a wonderfully relaxed attitude to life, clearly not a ‘sit and leave it to happen’ attitude, but more an active one that gets things done, but stays laid back.

I am always fascinated by the artfulness of those working in these vans with limited space and everything exposed to sight, but this is the smallest I have seen. I ask him what happens if he needs to cook more than one burger and he explains how he part-cooks sausages and burgers when it is busy so that he can serve them quickly. It seems such a small beach, but he says he is making a living. The café has been closed for a couple of years and he filled the void, but it is due to open again next season. There is no hint of chagrin or undue concern, he seems to have a wonderfully relaxed attitude to life, clearly not a ‘sit and leave it to happen’ attitude, but more an active one that gets things done, but stays laid back.

He tells me about his son who has got a degree in some form of marine engineering, but after working on a boat for a while and not being satisfied, is now ‘in catering’ like his dad. He and his mother are running another, larger van in an industrial estate at Pembroke Dock. He tells me about their search for a suitable van, the ones that were for sale nearby were all far too expensive, but they heard about a place down south (and I mean the far south of England!) where large numbers of catering vans are bought and sold, and here they found a suitable van.

They only started the new business this season, and it takes time for this kind of business to grow as people need to find it and then return, but the customers are growing. He is obviously proud of his son, who is meticulous about the food, seeking quality suppliers, including a local butcher with prize-winning burgers … and this is the burger I am to eat, which cost me the princely sum of £2.50.

Hearing about the son’s care for detail reminded me of Alan, up on Tiree, who, with Jeanette his wife, now runs the Cobbled Cow café. Before he had the café he ran a small catering van in the car park in Scarinish. Outside the van he had small tubs of herbs from which he would take clippings to garnish even the simplest food – fresh herbs on your burger. There is a wonder and a gloriousness in this. We are used to an age of fast food and ready meals, pre-packaged, and good enough. Here is a heroism that takes care in the small things, that treats a burger with the value of a cordon bleu meal.

I had been looking forward to the shade of the café, but instead sit with my burger and tea on the sea wall. I am still amazed that in normal life I avoid sitting or eating in the sun as I find the light too bright, but because I have to I am walking through the peak of noon. This day I sat and enjoyed the prize-winning burger and watched the waves play.

A lady in a uniform I do not recognise wanders across to look at a noticeboard. It turns out she is from the Customs … the modern version of the revenue men who tried to retrieve the whisky a hundred and ten years ago. She explains how they have to check boats even at small ports like Angle, although I think they were here at West Angle to get lunch, not in the expectation of a boat turning up. I would have liked to find out more, but she is called away by her colleague – maybe a report of a smuggler sneaking into a secret cove, or more likely a French yacht berthed at East Angle.

Rosie had warned me about the portion of coast between here and Freshwater West, the large beach three or four miles further on facing directly out into the Atlantic. She described it as ‘challenging’, but as far as I could tell she meant exhausting up-and-down challenging rather than life-threatening, blob of strawberry jam challenging.

Indeed, partway along there is a warning notice saying:

‘This is a challenging stretch of the Pembrokeshire Coast Path‘

It also says:

‘Please keep to the path and avoid the cliff edge.’

Ok, so maybe an element of strawberry jam too.

In fact, I felt safe along the route, at most there were one or two places where the edge got close, but nothing like the Fishguard–Newport stretch. However, it does have quite a lot of undulations, so you do want plenty of puff.

Along the way, there are a variety of military remains, from a ruined Medieval tower to Second World War gun batteries, the rusting mount points on dry concrete catching the essence of the sintering heat. Although Pembroke did not escape the ravages of German bombing, these shore defences, and the Napoleonic ones beyond, never saw action, the last attempt at a sea invasion being the foiled French invasion at Fishguard in 1797.

At Freshwater West you can walk the length of the beach as far as the car park at the south end. It is clear when you have got there, both by the surfers, but also the lifeguard’s hut. It was the first time I’d seen lifeguards riding quad-bikes, which they can use to rapidly drive the length of the beach should someone get into difficulties outside the designated swimming area.

At Freshwater West you can walk the length of the beach as far as the car park at the south end. It is clear when you have got there, both by the surfers, but also the lifeguard’s hut. It was the first time I’d seen lifeguards riding quad-bikes, which they can use to rapidly drive the length of the beach should someone get into difficulties outside the designated swimming area.

It is a wonderful beach, stretching for about a mile and opening nearly due west to catch the Atlantic breakers. The north end is quiet with just the occasional person and even the ‘busy’ south end by the car park has just a few dedicated surfers and beachgoers, even on a glorious day like this. I think it gets busier at weekends, but far out at the edge of Pembroke it is never going to be a Blackpool.

It is busy enough to support a bistro-style catering van, which sold burgers, but also seafood. One of the lifeguards was there catching her lunch and recommended the mixed seafood wrap, but having had a burger at West Angle, I didn’t think I could justify it as well as my doorstops, so I settled for a bag of fries and a cup of tea.

It is busy enough to support a bistro-style catering van, which sold burgers, but also seafood. One of the lifeguards was there catching her lunch and recommended the mixed seafood wrap, but having had a burger at West Angle, I didn’t think I could justify it as well as my doorstops, so I settled for a bag of fries and a cup of tea.

The lifeguard and the girl serving at the stall told me how part of one of the Harry Potter films, The Deathly Hallows, had been filmed here. The lifeguard was still in school and came down to see the set, which included the shell house. She had hoped to get a part of the shell house as souvenir, but it was removed entirely, evidently just before the filming of Russell Crowe in Robin Hood.

I had a strategic decision to make. My original plan had been to get to West Angle or to Freshwater West, and I was already at the latter, a 19-mile day so far. It was a bit after four o’clock and the bus was due sometime after five, which would take me back to the van in Pembroke. Although I’d already walked a long day, I knew that the next day was forecast for rain, so it would be worth shortening the next day by walking as far as I could on this glorious sunny afternoon. So I decided that I could walk along the road towards Castlemartin. If the bus passed before I got there I could simply flag it down, as the walkers’ buses stop anywhere.

Beyond the car park, dunes continue across the clifftops and on to Frainslake Sands. However, this is all in the military firing range; although no shots were fired in anger from these shores during the Second World War, many have been fired in exercises since the land was taken over by the MOD at that time. The eastern end of the range is open when there is no actual firing, but the west end, near Freshwater West, is permanently closed due to the dangers of unexploded ordnance. Looking on the map, as well as the expanse of beach at Frainslake Sands, there are also many archaeological sites.

Substantial areas of the South Wales coast were, and still are, in MOD hands for firing practice and exercises, as are large tracts of the Brecon Beacons; the setting up of these often involved the complete evacuation of farming villages and the destruction of communities. This occupation was one of the complaints of the Free Wales Army and other armed resistance groups in the 1960s.

There was no sign of firing or Welsh paramilitaries today as I walked along the road to Castlemartin. I had been told by the taxi driver that there was a new route for the Coast Path near Castlemartin, following an old tank track. He said it was possible to download a leaflet and map from the Wales Coast Path site, but my older version of the map did not show this. I could see where it branched off, but wasn’t sure enough of the route and didn’t want to miss the bus, so stayed on the road. Looking now I can see that it simply runs parallel to the road, rejoining it at Castlemartin.

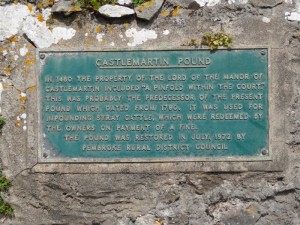

I made good progress and it was still before five when I got to Castlemartin. It is little more than a hamlet, with a scattering of houses. In the middle is The Pound, an enclosure that was once used to impound straying cattle and now has been turned into a tiny community garden.

Maybe if there had been a pub here that I could have waited in I would have stopped here for the day, but there was nowhere to shelter. I had been walking for ten hours and covered twenty-two miles, but still felt strong. I had been told by the taxi driver that there was a good pub in Bosherton, or ‘Bosh’, and, although this was another six or seven miles, I was still going strong, and the path looked as if it would be easy going along roads and the clifftop path in the firing range.

In fact, I was lucky. Usually the whole firing range is closed except at weekends, but there was no firing this week, so I would be able to take the route that leads down to the sea between the west and east ranges, and then follow the clifftop from there.

I was decided, and committed myself, walking past the unoccupied sentry post and along the road, closed to normal traffic, but open as part of the Coast Path. The road was eerily empty, and I kept rough track of how far I had come by the sight of the buildings of the village of Warren to the north. On days with firing the path leads along the road through Warren, and then out past the base at Merrion Camp, but today I could walk the two miles along this road and then turn down another mile and half through the range towards the sea.

It was odd seeing signs directing tanks as to which roads they were or were not allowed to follow. I guess this is a combination of the damage caused by caterpillar tracks on ordinary road surfaces, and the need to keep relatively slow tanks separate from other vehicles. Occasionally there are buildings visible in the otherwise empty ranges, and a church tower. I think I had expected to see any remaining buildings pockmarked and shattered, but they just try to avoid hitting them during firing. The other buildings visible are various bunkers; some, I assume, for firing from. Indeed one set looks as if they are where tanks draw up into. Others look as if they are for spotters to shelter in and then report where shots have hit.

It was odd seeing signs directing tanks as to which roads they were or were not allowed to follow. I guess this is a combination of the damage caused by caterpillar tracks on ordinary road surfaces, and the need to keep relatively slow tanks separate from other vehicles. Occasionally there are buildings visible in the otherwise empty ranges, and a church tower. I think I had expected to see any remaining buildings pockmarked and shattered, but they just try to avoid hitting them during firing. The other buildings visible are various bunkers; some, I assume, for firing from. Indeed one set looks as if they are where tanks draw up into. Others look as if they are for spotters to shelter in and then report where shots have hit.

More occasionally there are abandoned tanks or armoured cars. Again, they are not as damaged as I would expect if they were being used for target practice, so maybe they are just there to add a element of realism.

The path hits the coast by where Elegug Stacks rise guillemot-coated from the sea. The limestone is cut and eroded into headlands and natural arches, which then collapse leaving almost impossible stacks rising from the waters. They form natural nesting sites for vast flocks of sea-birds. Evidently these stacks are named from a Welsh word for guillemot (heligog).

The path hits the coast by where Elegug Stacks rise guillemot-coated from the sea. The limestone is cut and eroded into headlands and natural arches, which then collapse leaving almost impossible stacks rising from the waters. They form natural nesting sites for vast flocks of sea-birds. Evidently these stacks are named from a Welsh word for guillemot (heligog).

A little further on is Huntsman’s Leap. I recall seeing images of this on a documentary many years ago, and always wanted to see it for real. Instead of cutting away soft rock and leaving harder rock as a headland, a vein of softer rock has been cut away, either from the sea inwards forming a blowhole, or maybe from a sinkhole outwards; after further erosion, all the rock is removed from the exit hole to the sea, leaving a deep slit inwards towards the land.

There are signs saying not to stray from the path inland to avoid unexploded shells, but it was not clear whether you could wander and walk closer to the cliff edge. I imagined finding boots, the feet of past walkers still in them, and decided to play safe. Later, from the patterns of trodden paths I decided that in fact it was fine to stray in the sea direction with no fear of being blown up.

However, approaching Huntsman’s Leap you realise that playing safe is no bad thing. The sea has cut a slit into the cliff so that if you walk close to the edge, the slit cuts off your path ahead. In some places the slit is quite wide and easily visible, but near the cliff edge it narrows until it is barely six feet across, however the chasm below drops 200 feet to the sea.

However, approaching Huntsman’s Leap you realise that playing safe is no bad thing. The sea has cut a slit into the cliff so that if you walk close to the edge, the slit cuts off your path ahead. In some places the slit is quite wide and easily visible, but near the cliff edge it narrows until it is barely six feet across, however the chasm below drops 200 feet to the sea.

The story goes that a huntsman was riding along the cliff edge. His horse, seeing the gap, jumped clean over and landed safely on the other side, but, as the horse landed, the huntsman looked back, saw the chasm that he had just leapt over, and promptly died from shock.

Even after I had decided that the cliff side of the path was safe, I still kept mainly to the military path, which was either concrete or cinder, and fast walking. It was now approaching seven and I was beginning to look forward to getting back to the van.

To the inland side of the path, in the danger zone, were more occasional bunkers and an armoured troop carrier. On the seaward side of the path I passed one group of climbers, two watching from the cliff top, while their colleague, well roped, made his way down the sheer cliff, fixing protection as he went down.

To the inland side of the path, in the danger zone, were more occasional bunkers and an armoured troop carrier. On the seaward side of the path I passed one group of climbers, two watching from the cliff top, while their colleague, well roped, made his way down the sheer cliff, fixing protection as he went down.

As I got to St Govan’s Chapel a couple, Mark and Liana, with their black and white dog, were also making their way down the steep stone steps. Having seen the height of the cliffs earlier, I was preparing myself for a long descent and equally long ascent on the way back. However, I was relieved that the cliff is low and the chapel about half way up.

As I look at it from above I have a feeling we visited here with the girls when we camped at Tenby many years ago. We were living in Stafford at the time and, as always, I was trying to finish various things off on the Saturday before leaving for our week’s holiday. It ended with a frantic dash across mid-Wales to try and catch the campsite reception before it closed. In the end we failed, so stayed the night in their special latecomers’ area before setting up properly the next day. This was in our old VW camper, not the swish camper I have today. I do like having the proper toilet/shower and the extra space, but the VW was such fun!

As I look at it from above I have a feeling we visited here with the girls when we camped at Tenby many years ago. We were living in Stafford at the time and, as always, I was trying to finish various things off on the Saturday before leaving for our week’s holiday. It ended with a frantic dash across mid-Wales to try and catch the campsite reception before it closed. In the end we failed, so stayed the night in their special latecomers’ area before setting up properly the next day. This was in our old VW camper, not the swish camper I have today. I do like having the proper toilet/shower and the extra space, but the VW was such fun!

From above it doesn’t look as if there is any access to the chapel as it fills the narrow gap between the cliffs and all you can see is its roof. However, as you get to it, there are steps running down to a low arched entrance. You enter on the landward side of the chapel, and then go out the other side to go down to the sea.

The story goes that St Govan was threatened by marauding Irish pirates. He prayed and a fissure opened in the cliff, which then closed round him, hiding him from the murderous raiders. The chapel was built around the fissure, which I assume had reopened after the Vikings left, and the marks of Govan‘s ribs can be seen moulded into the solid rock.

Below the chapel is what appears to be another tiny building. Mark and Liana had read a guidebook that said it is a tiny hermit cell (Wikipedia says a Holy Well), but with an entrance just knee high I reckon it can only be one thing, the chapel for St Govan‘s dog.

Below the chapel is what appears to be another tiny building. Mark and Liana had read a guidebook that said it is a tiny hermit cell (Wikipedia says a Holy Well), but with an entrance just knee high I reckon it can only be one thing, the chapel for St Govan‘s dog.

I chat for a long time with Liana while Mark meditates in the chapel. As we all climb back up to the clifftop and the car park, I tentatively ask whether they can take me as far as Bosherton. If you are walking during firing times, the path comes down the road past it, but on the cliffside route it is bypassed entirely and I would have had to walk another mile off track.

They drop me at St Govan’s Inn and I ask for a pint and a phone … I have to get things in priority order, and I start to write about the day so that as I finish my pint the taxi arrives to take me back to Pembroke and the van.

This time I give the five-minute Indian a miss and instead get a Szechuan Beef from the Chinese by the car park. I make my way to Freshwater East, which will be my destination for the next day, but the caravan site is closed and doesn’t have a late arrivals area, so I end up driving back at the car park at Freshwater West to eat gazing out over the wild dark sea.