First, the discovery. As I began to pack my bags for the day I gathered together things from the floor around the rucksack, and there, just under a t-shirt, was a small black device, too fat for a phone … the lost Garmin! We had searched at the beginning of the walk, I had emptied the rucksack at Nash, and yet here it was. It must have slipped down somewhere in the rucksack and evaded my search, I have no idea how.

This was good news as it was no long lost, the bad news was that a replacement had already been ordered. However, the lost Garmin belonged to the university, so it means I now have one of my own.

It booted enough to tell me its battery was low, but had clearly managed to record the first day and most of the second day before its battery ran out.

After my breakfast at ‘Rest for the Tired‘, I left my large rucksack with the proprietors to take on to Kington, set my day pack upon my back and went up the road to the small electrical store I’d noticed the day before, in search of batteries.

[continued below April 2014]

At first I thought the shop was empty, but then from the back of the shop the proprietor emerged. I already had lots of rechargeable batteries, but they were in the van, so I just asked the shopkeeper for two batteries. He broke open a 4-pack and then, while I paid for them, he noticed my pack and asked about the walk. I mentioned that I was interested in community issues in places along the way.

"Funny you should say that", he said, "just as you came in I was in the middle of typing last night’s minutes."

It turned out he was chair of a group trying to buy the local fishing rights for the community. The idea was to make it easier for local businesses to offer hire of rods and short-term permits to make the most of the river as a tourist amenity. Having no web presence then (nor yet as I write), they were digitally invisible, and I felt thankful for this ‘happy accident’ that led me to his door at this very moment. In support of the walk he threw in the other two batteries from the 4-pack, and I set off on my way.

The path out of Hay-on-Wye leads over the river bridge and then along the west bank of the river for a mile or so, before cutting up the hillside beyond. The way goes through woodland, but after a short while there was a diversion sign due to forestry operations, and sure enough some way ahead I could see large yellow vehicles at work and the sound of engines and saws.

Unlike the diversion between Brockweir and Llandogo, this was clearly marked with small paper notices in plastic bags. The diversion led through fields at the edge of the woods to the left-hand (southern) side of the normal path, but eventually had to cross over to the far side as the path struck a more northerly direction.

For the first few days of the walk, as far as Monmouth, I had worn training shoes, as I wasn’t expecting hard going, but happily had changed to boots at Monmouth. Where you had to cross the forest track it was rutted with caterpillar tracks at least a foot deep. I look at it and wish I had gaiters as well as boots. Happily the weather had been very dry, and what looks like deep mud is nearly solid, although I did need to take high steps to get my feet from rut to rut.

I was crossing the rutted forest path at a junction, and so almost followed the path opposite the way I’d approached, but then noticed orange arrows blazed on a tree trunk leading up into the woods, only then I also saw one of the plastic coated signs. Further arrows were painted on the ground.

I was crossing the rutted forest path at a junction, and so almost followed the path opposite the way I’d approached, but then noticed orange arrows blazed on a tree trunk leading up into the woods, only then I also saw one of the plastic coated signs. Further arrows were painted on the ground.

I have no idea whether this was the forest contractors marking the way or other ramblers doing it. However, I did recall an email I had had just a few days ago from the LDWA (Long Distance Walkers Association) about arrow painting in the Peak District. The email reported that there had been incidents where bright arrows had been illicitly painted by ramblers, and reminded LDWA members that this was criminal damage, and that the LDWA would cooperate fully in any investigations.

While I am sure this is strictly true, I can imagine that in difficult places additional signage would be most helpful, particularly at dusk. It is surely in no one’s interest to have people go astray, whether this is simply inconvenience, leads to accidental damage to fences as people try to find their way after getting lost, or even have to call out rescue services.

I don’t know whether the arrows I followed were official or illegal, but I was grateful for them.

After the muddy patch I was quite glad as the path went first up a grassy field and then on to some road walking along a little country lane. For a few miles the way alternates between tiny roads, green lane and open field, running around the slopes of Little Mountain. Eventually I came to the little village of Newchurch/Radnorshire.

As you enter the village from the south, the church of St Mary is pretty much the first thing you see, and, before you enter the churchyard itself, a notice board. On the notice board was an announcement of a theology lecture at Swansea University and beneath that the words:

"Refreshments"

and

"Dykers and visitors refreshments in church"

What more can you ask, except there was more …

As I came into the churchyard through an old iron gate, I found amongst the gravestones a wooden picnic table, against which were leant a number of walking poles and rucksacks, and inside the church lounging on the pews, of course, the Three Dykers.

They had, once more, set off a couple of hours earlier than me, and had stopped here for lunch; I had caught them just before they set off again. They were hoping to get to Gladestry before pub closing time in order to get sustenance for the last pull over the Hergest Ridge into Kington.

I too needed to get on as I was due to meet Paul Sandham at Kington, but was worried that I wasn’t making sufficient time – I still had not quite come to terms with my real walking pace when I had made the plans to meet, and was worried I would be late.

So I stayed long enough to look round the church while drinking a cup of tea and then set off. There was a small poster about Kilvert’s Diaries. He didn’t have any particular connection with this church, but this area was his stomping ground.

At the other side of the village is a small Methodist Chapel. On the notice board a single message:

I was glad when they said unto me

Let us go into the house of the Lord today

Psalm 122 v.1

Unfortunately the door was locked.

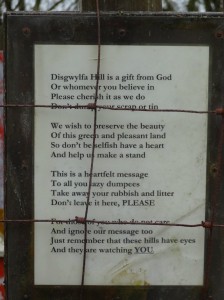

Going over Disgwyllfa Hill I soon caught site of the Three Dykers ahead, and caught up as they stopped to take in the view at the top. I was worried about missing Paul, so hurried on down.

More haste less speed.

I stopped to take photographs of a particularly distressed signpost, and then continued down the hill where there seemed to be a series of large Neolithic market stones, but closer up turned out to be bags of animal feed. I was at the bottom trying to make sense of the map and what I could see on the ground when I heard a whistle from high up the hill. It was Paul gesturing to me. When I had stopped to photograph the signpost it would have also been sensible to look where it said to go.

I stopped to take photographs of a particularly distressed signpost, and then continued down the hill where there seemed to be a series of large Neolithic market stones, but closer up turned out to be bags of animal feed. I was at the bottom trying to make sense of the map and what I could see on the ground when I heard a whistle from high up the hill. It was Paul gesturing to me. When I had stopped to photograph the signpost it would have also been sensible to look where it said to go.

After getting back up the hill and then back down the right way, it was less than two miles into Gladestry, but by the time I got there it was less than half an hour before I was due to meet Paul Sandham in Kington, with the whole of the Hergest Ridge between.

With some difficulty I managed to find phone signal, but got through to Paul‘s voice mail. I said I was only at Gladestry and suggested he come there instead and that I’d wait at the church.

It didn’t take me long to realise this was a silly thing to say as I had no idea whether he would have got the message, so rang again to leave a second message to say to ignore the first … but then still didn’t know whether he had picked up the first before I sent the second.

So I waited for a while at the Norman church in Gladestry. It was another St Mary’s and it too had tea 🙂

In the churchyard was the most beautiful miniature garden with a child’s seat, flowers and small toys. As I was drinking my cup of tea a lady came in to pick up a flower vase. She told me that a child had died tragically some years ago. The family maintained this garden as a memorial.

Eventually I decided that the best thing was to assume Paul never got my message and go on to Kington and hope that Paul had not waited too long for me.

As I left the village I peeked at the pub, but it was now long closed so the Three Dykers must be well on their way to Kington.

The way out of the village starts off on a small lane that runs steeply up the first slopes of Hergest Ridge. Just before the lane gave way to open ground there was a house to the side of the lane. The slope of the land was such that the lane ran at eaves level where a small basketwork bird ‘box’ was placed, like a miniature bee skep. I was puffed climbing it once, but the people who lived there would be up and down this hill every time they went out.

The Hergest Ridge is about three miles from end to end. Unfortunately, I did not have my glasses on, which was fine from a navigation point of view, but meant that in all my audio recordings I referred to it as "Hengest Ridge".

Towards the top of the ridge there was a rectangle area with raised grass around it edges. At first I thought this was the remains of an ancient chapel or moorland farmhouse, until I found an exposed corner of what appeared to be reinforced concrete, so I thought instead a wartime construction. I have later learnt (Wikipedia page on Hergest Ridge!) that there was once a race course on top of this hill in the early and mid 19th century, so now I wonder whether it was something to do with that.

Looking north a large quarry dominates the landscape, digging what I guessed to be limestone, from lesser hills, but the rock of the higher ridge is either not suitable, or too difficult to get out, as it is free of quarries, and the home of grass, horses and sheep.

The path skirts the north west side of the main peak following the line of the old race course, passing close to the Whet Stone, a large erratic boulder dropped there during the last ice age. However, it does pass directly over the lesser peak before the descent into Kington. This smaller peak is topped with a small stand of trees, which I initially took to be firs, like the six pine trees in the Hundred Acre Wood.

As I got closer they looked less and less like firs or pines, until I realised they were in fact monkey puzzle trees.

I have always loved monkey puzzle trees since the days when we would drive up to Brecon to visit Mum‘s old wartime landlady. On the way into Brecon, on the left hand side of the road, was a monkey puzzle tree as high as the house.

These were good sized trees, so had been there some years. There was a plaque, which I hoped would tell the story of the trees, but was instead for a seat that had been placed there just a few years earlier.

Puzzled myself, I made my way down the slope on the last mile and a half before Kington, passing a lady out running … about to run up the slope I’d just walked down. They are made of tough stuff in this part of the world.

And of course, it will be no surprise, that as I walked down these last few lanes before Kington, I caught up again with the Three Dykers. Their bed and breakfast was just behind the church as we entered Kington proper, so we parted company after only a few minutes. This would be our last meeting as I was taking a break from the trail to go to the CHI conference in Paris while they would continue up north and finish a week or more ahead of me.

Less than fifty yards further, the wall of the churchyard bulged out where an old piece of tree trunk broke through with the stones surrounding it. I touched it, stroked it; it was so smooth where everyone who passed was tempted to similarly touch it polishing it by finger tip.

An elderly lady comes along accompanied by what looked like the smallest Irish wolfhound imaginable, not a small dog by any means, but just small for its kind, maybe a cross with a greyhound. He was called Amadeus. I wonder if she knows anything about the monkey puzzle trees.

An elderly lady comes along accompanied by what looked like the smallest Irish wolfhound imaginable, not a small dog by any means, but just small for its kind, maybe a cross with a greyhound. He was called Amadeus. I wonder if she knows anything about the monkey puzzle trees.

"Are you a local?", I ask.

"No", she instantly replied, "I’ve only been here 20 years".

Unlike many towns and villages where the flows of population mean there are no longer roots, Kington, perhaps because it is a backwater, poorly connected, still has a number of old families, and it is hard for an incomer to become really part of the community without marrying into one of these families. I guess this is not so different from Tiree; the doctor has been here over 30 years, and is certainly a part of the community, but still definitely an incomer. But I notice a subtle difference, if I asked him, or if you asked me, we would say we are "local", just not native to Tiree.

Maybe I am making too much of a word (and the speed of response), but I wonder if the divide here between incomer and native is deeper. However, I also wonder if this is another example of permeable boundaries making borders more contentious. On Tiree those who come to live make a big commitment to the geographic space, it is bounded by sea and you can’t simply have a house there. On the mainland many smaller towns and villages become just that, dormitories, places where people have a house but maybe have their lives elsewhere. While this particular lady was clearly not in this category, still I wonder if the ease of transport that blurs its geographic boundaries can make a community more insular, whereas the clarity of an actual island community breeds a sense of cohesion. On Tiree, ten miles of open sea is a clear indication of who is and is not local.

Yvonne does not know the origins of the monkey puzzle trees, and after few minutes chat we part our ways, but as I turn to go towards the town, someone calls my name. Coming towards me is Paul. We have never met, but I guess not many people are wandering into town with a banner on their back.

He has been waiting for some time. He had never got my messages, but had been catching up with emails on a different phone (which did have signal). He has a small company that creates map- and trail-based software for mobile phones, so tends to have a selection.

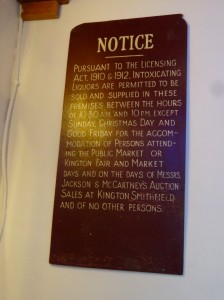

We make our way to a tiny pub he had spotted earlier, the Wine Vaults, which has its own microbrewery, and incidentally the most gloriously painted toilet, albeit at the back of the yard, so best not viewed in a thunderstorm.

The locals were very helpful trying to find someone who knew the history of the monkey puzzle trees. The best answer seemed to be that the head of a local well-to-do family, the Banks of Hergest Croft, had been a bit of a plant collector; many years ago, I’d guess towards the turn of the 20th century, he had placed them there, not as any sort of memorial, but just because it was a good place to plant some specimen trees.

Paul didn’t have long as he needed to get back home to Caernarfon, pretty much diagonally across the whole of Wales. However we did have time to share a pint of Arrows Beer, to talk about mobile maps, GPS traces, and mobile content creation, and to arrange for me to visit when I got to Caernarfon in a month or so’s time.

I was staying at the Youth Hostel, the first time I had done so. In years gone by you needed to take your own inner sheet sleeping bag, but now you have clean linen, can hire towels and even, for a supplement, have a room of your own. As it was quiet I ended up with a small two bunk-bed dorm with en suite bathroom all to myself.

I ended the day eating a bar meal at the Oxford Arms, to the occasional sound of whoops from the function room where the Young Farmers were having a games evening.