The route from Monmouth to Pandy is relatively gentle over fields and through lanes, with the occasional small hill. It was my first day sending my main pack ahead, so much easier than some previous days, and also I was accompanied for the whole day by Les.

Les and I had arranged to meet at the Monnow Bridge, an original gated entrance to the old walled town. We had never seen each other before, but we were easily recognisable by our rucksacks and boots. I had posted onto the forum of SaySomethingInWelsh, a Welsh language learning website, to say that I was walking round Wales and would welcome meeting anyone along the way. {Les} answered.

Les and I had arranged to meet at the Monnow Bridge, an original gated entrance to the old walled town. We had never seen each other before, but we were easily recognisable by our rucksacks and boots. I had posted onto the forum of SaySomethingInWelsh, a Welsh language learning website, to say that I was walking round Wales and would welcome meeting anyone along the way. {Les} answered.

Les, a Lancastrian by birth, had lived and worked in Monmouth for 20 years, and six years ago had decided to learn Welsh. He discovered the SaySomethingInWelsh online materials and had not looked back. SSiW emphasises listening and speaking, with lots of repetition, rather like ULPAN method. One of my hopes while walking was that I would spend periods listening to Welsh learning audio in a little iPod nano that I’d had for Christmas, precisely for this purpose. Fiona had found the SSiW site and downloaded the complete set of MP3 files. Unfortunately, I did not find them easy to get along with as I really need to see something written before I can remember it, some sort of auditory equivalent of dyslexia, I can hear very fine details in sounds, but if I try to reproduce them I fail!

Les is actually part of a trend, Monmouthshire was the only area in Wales to see an increase in Welsh language speaking at the last census. Les also noted that red kites, often used as a symbol for the Welsh language, had also recently been seen in Monmouthshire.

Although he had never walked the Offa’s Dyke route before, Les had rambled over much of the countryside in the area (a more seasoned walker than I!) and often we would be on ground that he knew well. We started going out along a lane and then well-made paths past fields and through woods.

When we had been in touch, Les had said he would bring food for the day. Given my problems two days before, I needed to take lessons from his experienced approach.

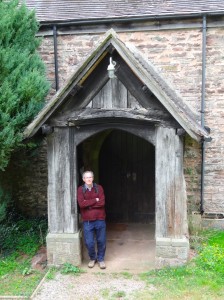

Our first stop was at a small church, St Michaels, at Llanvihangel-Ystern-Llewern, where we sheltered a little in the porch and ate banana and flapjack, the rubbish going back into a plastic bag that Les kept in his rucksack for this purpose. In the porch were various notices about the church, including one advertising a cancer care hotline operated by Tenovus, one of the charities I am collecting for on the walk.

In the graveyard were the usual collection of gravestones, some so old that the letters have all but disappeared. But amongst these a number of metal crosses, burnt rust red amongst the long grass. I don’t recall seeing this anywhere before.

Before we left Les pointed out the name of the village. I didn’t understand the significance until he explained: Llanvihangel-Ystern-Llewern is the longest true place name in Wales.

audio: Les on Llanvihangel-Ystern-Llewern

I have always thought that Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch was the longest placename in Wales, but this name was a 19th century invention.

I have always had my own story about Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch, inspired by the film "The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain" (incidentally the story of Garth Hill a few miles north west of Cardiff). I imagine the urbane English mapmaker in tweeds and his nervous assistant speaking to a local Welshwoman in black hat and red checked skirts.

"Madam, if you would be so kind, what is the name of this place?"

She looks bemused.

The assistant has picked up a little broken Welsh, and tentatively asks, "Ble ydw i?"

Her eyes light up, "Llanfair", she says, which means "St Mary’s", but of course there are many places called Llanfair, so she expands, in Welsh, but here in English paraphrase, "Oh the St. Mary’s in the hollow of the white hazel near the rapid whirlpool at St. Tysilio of the red cave."

The assistant dutifully writes this all down in his leather-bound notebook, occasionally dipping his pen into its portable inkwell, while the mapmaker gazes disinterestedly into the distance.

And so the little old lady’s directions on how to get there became the place name on the English map.

I like my version of the story, but sadly, the truth is more prosaic, a PR stunt in the 1860s to market the railway station on the newly opened London–Holyhead line.

Beyond Llanvihangel-Ystern-Llewern the path alternates between sections along small country lanes, and crossing grassy fields. Although we stay on the Welsh side of the border all day, we are not far from Herefordshire, the heart of cider making, and we pass the occasional orchard.

I was a little lazy with my direction finding as Les knew many of the paths, but once he seemed to be taking the wrong way across a field when the marker post was telling us to skirt along the edge, but just five yards in he stopped and showed me a deep rectangular slit in the ground, with mud covered stone steps dropping down into darkness. From only a few yards away it was invisible, like an entrance to a secret passage out of Famous Five. He had been shown it himself by another walking companion some years before and in turn showed me this hidden secret.

Despite passing it before, Les had never gone down into its depths, but, maybe emboldened by his role as guide, he stepped slowly down the treacherous steps, each almost angled up to the next by a thick accretion of washed earth. Stiff grass and bramble grappled from each side, and the sides of the narrow passage brushed our elbows, our rucksacks abandoned at the top.

We stood at the bottom, me peering over Les‘s shoulder into the darkness of the buried threshold. Neither of us had a torch, but we each took a flash photograph. Instead of the red glow of troll eyes, there was the dull grey of pipe work. Maybe half a mile over the hillside we had seen a large house near a church and we guessed this was something to do with its water supply.

We started to walk away, and then, happily before we had gone more than ten yards, I put my hand to my neck and realised my glasses were not hanging from the neck of my t-shirt as they normally were. Retracing our steps slowly to avoid stepping on them, we looked down the steps into the ground, the most likely place, and sure enough Les found them part way down, in the mud but thankfully not trodden on.

I never really sorted out the problem of the glasses. For a while after this I used to keep them in a plastic wallet with my phone, but then risked squashing them in my pocket. Later I kept them with the map, but with similar danger. As it was always a bit of a pain pulling them out I ended up reading the map without glasses, which did hinder my orienteering skills, and led to some strange misreading of names on my audio tapes. A long time after, I gave up on the plastic wallets and hung them back inside my t-shirt, but with the glass side inside so they were unlikely to fall out. This was more secure, but meant that they were completely misted whenever I tried to use them.

Les seemed to know half the people in the area. A few miles beyond Llanvihangel-Ystern-Llewern, we passed a stone cottage and Les said, “let’s knock and see if we can get a cup of tea”. At first I thought he meant to beg tramp-like for refreshment, but in fact Marge was an old friend of his, and brought us tea and biscuits around her blazing wood fired stove.

We talked about the closure of local pubs, garages and shops over the years, but also those that survived, shaping themselves to the modern age, less a regular evening haunt of locals around the corner, and more bar meals and a pint in the country for town dwellers out in the car, or weekend wedding receptions. I also learnt about a local author collecting tales of a folk hero of the area, an ordinary man winning over formidable foes by wile.

On the stove a fan was spinning. Marge explained that it was blowing hot air from the stove into the room, and thought it worked in some way due to convection. However, when I looked more closely there was an electric motor driving the fan, with the wires connected, not to a battery, but to some metal plates.

On the stove a fan was spinning. Marge explained that it was blowing hot air from the stove into the room, and thought it worked in some way due to convection. However, when I looked more closely there was an electric motor driving the fan, with the wires connected, not to a battery, but to some metal plates.

Only a month or so before I would have wondered how this worked, but while preparing for the walk I had come across the BioLite CampStove. This is a small wood burning stove that creates intense heat from the smallest twigs by using a small electric fan to drive air through, like the bellows in a blacksmith’s fire. The fan is powered by thermoelectric material in the sides of the stove, which generates a small voltage when heated. The electricity also powers a small USB charging power, so not only can you brew a cup of tea, but charge your phone at the same time.

This fan was working on a similar principle, but with small plates of thermoelectric material drawing heat from the stove.

Our next stop was at White Castle, near Llantilio Crossenny, a Norman castle built to control the local land in the 13th century. It is managed now by CADW who look after many of the castles of Wales. There was a small kiosk to pay for entry and selling CADW booklets and merchandise. Two women were on duty who, of course, Les knew well.

While we were there Les pointed out to me the site of a proposed solar energy farm, 42,000 panels over 67 acres. He was active in objections to the solar farm, not because he objected in general, but more the particular site. Partly because it was prime agricultural land, and partly because of the impact on the view from the Offa’s Dyke Path and White Castle itself.

"It would fine if they had some sort of quota for the county and then decided the best place to put them", he said.

However, the actual choice of sites depends on the external companies who wish to create solar farms, and farmers willing to have them in return for a long-term lease on their land. The places that then get chosen are not those that make most sense in terms of amenity, agricultural value and energy production.

audio: Les on the solar panels

After White Castle the path is almost all across open countryside, except for a couple of very short sections on country roads, one where I was surprised to see a Saltire.

As we crossed the brow of a hill and came over a stile, we came across three walkers sat on a fallen tree taking a short break, Paul, Ray and Lynne. I didn’t realise then, but they would become intermittent companions over the next few days.

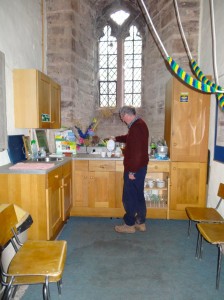

Not too far after we came to St Cadoc’s Church in Llangattock Lingoed. Les obviously knew it well, and as he led me to it he pointed out a weathered welcome note with an image of a tea cup on it.

The church is a medieval church that has recently been restored. It has original paintings on the wall and lovely timbers. If there was a church that had an excuse to keep things as original and traditional as possible, this was it. Yet instead, at the back of the church, in the nook underneath the bell tower, was a full kitchenette with kettle, tea and coffee, etc. It was a beautiful church, but most beautiful of all was the simple witness of hospitality.

Some while later, we came through a hedgerow into a gentle slope of pastureland down to a stream. Set against the dull brown and green of land still recovering from late Easter snows, were bright blue, red and yellow flags. They sat on metal spikes around 8 inches high. At first we saw a handful, but as we came lower more and more, probably a hundred and fifty or more, clustered along the stream side, but some coming up into the field itself.

Some while later, we came through a hedgerow into a gentle slope of pastureland down to a stream. Set against the dull brown and green of land still recovering from late Easter snows, were bright blue, red and yellow flags. They sat on metal spikes around 8 inches high. At first we saw a handful, but as we came lower more and more, probably a hundred and fifty or more, clustered along the stream side, but some coming up into the field itself.

Various explanations came to mind. When we had seen just a few, we thought maybe a trail, or some sort of treasure hunt where your team has to collect its flags as you run by; but as we saw more they were too many and too close. We thought maybe a nature survey marking the spots where some kind of flower bloomed, but some flags were set in the middle of the stream. Nothing made sense, they remain one of the unsolved mysteries of the walk.

For much of the day The Skirrid dominates the landscape. This consists of two peaks at either end of a long red sandstone ridge, Ysgyryd Fawr and Ysgyryd Fach rising from the largely flat land around Abergavenny. Their shape had changed through the day. Originally the ridge had been prominent, but as we passed to the north, the single peak of Ysgyryd Fawr was all that could be seen. However, nearing Pandy, due north, was the most spectacular view, with the twin peaks brought close by the angle and looking for all the world like the twin horns on a Viking helmet. The portion between had fallen in a landslip, it is believed in the ice ages, but local lore says that this was instead at the moment of the Crucifixion.

For much of the day The Skirrid dominates the landscape. This consists of two peaks at either end of a long red sandstone ridge, Ysgyryd Fawr and Ysgyryd Fach rising from the largely flat land around Abergavenny. Their shape had changed through the day. Originally the ridge had been prominent, but as we passed to the north, the single peak of Ysgyryd Fawr was all that could be seen. However, nearing Pandy, due north, was the most spectacular view, with the twin peaks brought close by the angle and looking for all the world like the twin horns on a Viking helmet. The portion between had fallen in a landslip, it is believed in the ice ages, but local lore says that this was instead at the moment of the Crucifixion.

Eventually, tired but happy, we came down the hill towards Pandy, where the path comes out onto the A464. The Lancaster Arms, where I was staying this night, was opposite.

Eventually, tired but happy, we came down the hill towards Pandy, where the path comes out onto the A464. The Lancaster Arms, where I was staying this night, was opposite.

We were greeted by Keith and Sandra, the landlord and landlady who told us where to hose down and then take off our boots (no mud inside!). Les was going to ring his wife to pick him up and have a quick pint with me while she came. But as we went inside, who was there but the Three Dykers who we had met on the way. It turned out that they had passed us at Llangattock Lingoed, not realising that they could get refreshments there.

Les tried to ring his wife, she works in a school, but would be home and waiting for him as it was already after 6:30pm. However, he could not get through, so sat down in the very comfortable bar area and enjoyed his beer. The Lancaster Arms used to be a pub, but closed the bar some years ago and is now a B&B, catering particularly for walkers for whom this is one of only a few places to stay in this section. Evidently walkers are less hard work than typical pub clienteles!

It was, to be fair, some time later when Les remembered to ring his wife again. It was obvious that the conversation was slightly frosty. By this time it was well after 7pm; he had set out with someone he had had contact with on the internet – for all she knew I was a wild axe man, or we had got stuck down a secret hole in a field (as if).

The frostiness had not completely worn off by the time she arrived to pick him up, so I hope she forgave him and me.

G’day from half-way around the world; researching family history has brought me to this area of Monmouthshire, which unfortunately, I have never visited when I lived in the U.K. Thank you for giving some idea of the topography surrounding Llanvihangel and Pandy, and the current rural situation. My ancestors lived in around this area with my great-great-grandmother’s siblings being born in the village. Their father was renown as a non-conformist preacher, considered fanatical, preaching on the highways and byways. According to the 1861 census they lived in a house connected with a turnpike road.